After nearly 15 years of shaping the live sound experience at Shibuya’s iconic WWW, the legendary MIDAS Heritage 3000 console is set to “graduate” as the venue upgrades its system. Revered for its unmatched sound quality and intuitive design, the analog console has been a favorite of engineers and musicians alike since its 1990s debut. As digital consoles dominate the scene, the Heritage 3000 is now a rare gem, with few venues still relying on analog sound setups.

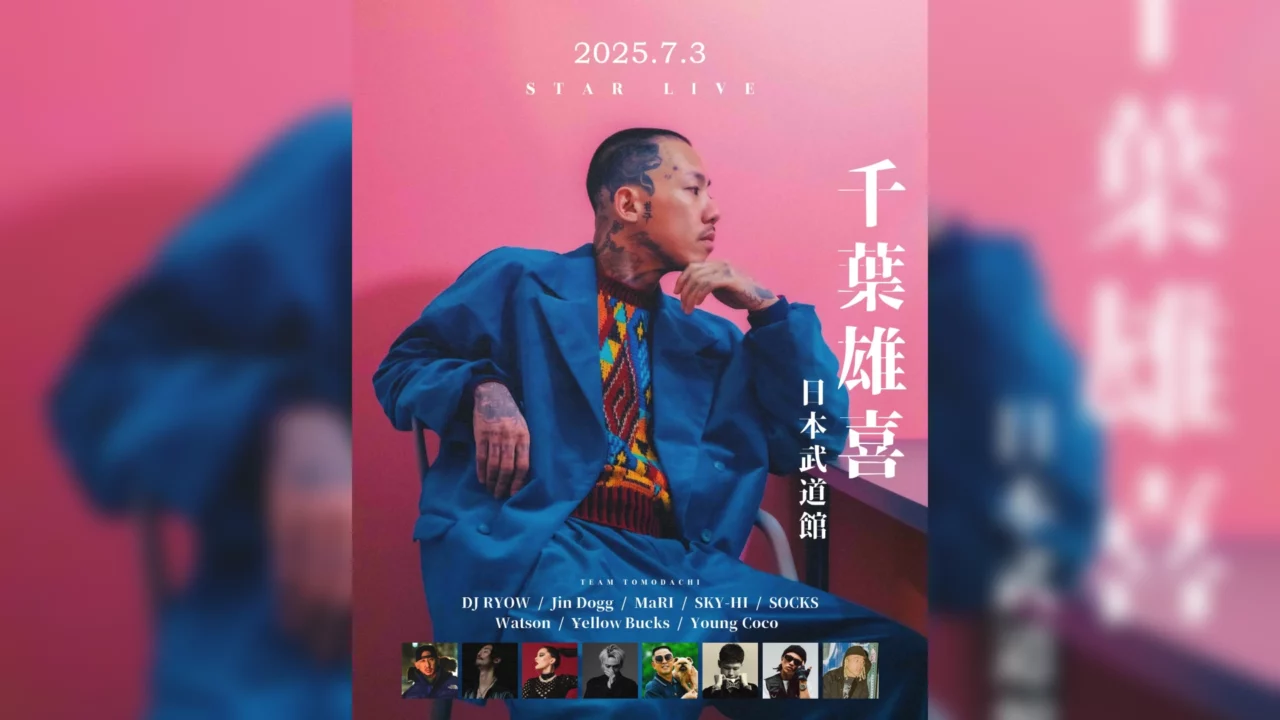

To honor the console’s legacy, WWW will present the “Heritage 3000 Farewell Series” from January 5 to 13, 2025. Featuring performances by some of Japan’s most groundbreaking acts—OGRE YOU ASSHOLE, MERZBOW, Saho Terao, Tabito Nanao, and many more—the series offers a rare chance to experience the unique sound of the Heritage 3000 in action.

In this article, we dive deep into the enduring appeal of the Heritage 3000 and what truly makes live sound extraordinary, with insights from top PA engineers Naoyuki Uchida, Yukio Sasaki, and Dub Master X. Join us for a behind-the-scenes look at the artistry of live sound and the console that captured the hearts of so many.

INDEX

The Pioneers: Sound Engineers Who Helped Shape Japan’s Live Music Scene

This interview was inspired by the farewell of the Heritage 3000 at WWW, but since it’s such a rare opportunity for everyone to come together, we’re excited to have a chance to discuss sound systems and live sound more broadly. Each of you has had your own unique career, but how long have you been working?

DMX: I started when I was 20, and I’ll be 62 after the new year… so, I guess that makes it 42 years? Time really flies! [laughs]. Sanchan (Sasaki), you’ve been at it about the same length, right? Since we’re the same age.

Sasaki: I joined the company (Acoustic Inc., where I’m now the CEO) when I was 22, so I’ve been doing this for 40 years.

President and CEO of Acoustic Inc. He has worked with a wide range of artists, including YMO, Sakanaction, Hitsujibungaku, Ayano Kaneko, Shinichiro Sakamoto, OGRE YOU ASSHOLE, and more. Sasaki is known for his versatile live mixing skills, working across music genres and both major and indie labels, handling everything from live houses to stadiums.

Uchida: I started working part-time at a recording studio when I was 20, so my first experience was in recording. I ended up getting into this work when the band DRY & HEAVY, who I was working with at the time, told me, “You should handle it.” I was around 25 or 26 at the time. I had no real knowledge, so it felt like I was driving without a license.

Born in 1972 in Sayama City, Saitama. Uchida began working at a recording studio in 1992, learning recording techniques. At the same time, he started working as a DUB engineer for DRY & HEAVY, a pioneering Japanese Roots Rock Reggae band. While participating as a band member and performing live, he self-taught live sound engineer techniques. He has also been a member of several domestic DUB bands such as LITTLE TEMPO and OKI DUB AINU BAND, continuously honing his skills to advance Japan’s DUB MUSIC scene.

You all seem to have a good relationship. How did you meet?

Uchida: I’ll start since I’m the youngest [laughs]. When I was younger, I was a huge fan of MUTE BEAT, and Miyazaki (DMX) was like an idol to me.

DMX: You flatter me [laughs].

Uchida: I really listened to them a lot when I was a student. If it weren’t for MUTE BEAT, I wouldn’t have even known about dub music. I couldn’t see them live, but I listened to their records like crazy. Miyazaki-san was truly a pioneer.

DMX: It’s true that I was a pioneer, but it was just because I happened to be doing it for a long time. I wasn’t trying to master reggae dub, I just liked the dub elements as sound effects. MUTE BEAT was just what I happened to be doing. People call me Japan’s King Tubby, Lee Perry, or Mad Professor, but I wasn’t really into those guys. I was more interested in people like Steven Stanley or Alex Sadkin, who brought the essence of dub into pop, rock, and punk. So, I think nowadays Uchida (Uchida) has taken dub to a whole new level.

Moved to Tokyo after graduating high school and studied audio engineering at a technical college. In 1983, he joined the now-legendary club “Pithecanthropus Erectus” as a mixing engineer. He became involved as a dub engineer with MUTE BEAT, and also worked as a DJ and PA engineer. From the 1990s onward, he collaborated with Hiroshi Fujiwara, Koji Asahito, and others, producing numerous remixes and arrangements.

INDEX

“Acoustic Crew, Led by Mr. Sasaki, Feels Like Family” (Uchida)

What is the relationship between Dub Master X and Sasaki?

DMX: I’ve had connections with the Acoustic crew since I was younger. Acoustic is an interesting company. They have a team deeply involved in major rock and pop music, and another one more focused on rave and club music… we call them the “Yama team.” The major music team is a very strict one [laughs].

Sasaki: The proper team [laughs]. The “Yama team” is the one that’s less organized [laughs]. We’ve been involved since the “RAINBOW 2000” days, so we’re more attuned to rave and club music styles.

(RAINBOW 2000 was the first outdoor dance music festival in Japan, held in August 1996, with around 18,000 participants.)

DMX: The “Yama team” was led by an engineer named Ono (Shiro), who has since passed away. Sasaki was part of Ono’s team. I originally worked with the more strict team, but since we were all part of the same company, I eventually started interacting with the Yama team as well. It was like, “Sasaki’s got great sound. I get that low-end vibe.”

Sasaki: The way the sound is constructed is properly “pyramid-shaped,” so to speak. I think that’s where the common ground was. You can tell immediately when you listen to the sound made by someone like that. They’ve definitely been through the club and rave scenes. It’s a huge difference from people who haven’t been through it.

DMX: Exactly, people who build sound like a pyramid are easy to spot. The sound stacked on top of the bass doesn’t get overwhelming.

Sasaki: And then, Uchii and I have known each other since the time he started coming in and out of LIQUIDROOM for DRY & HEAVY’s live shows. My company also manages the sound for live venues, so our engineers are always at the scene. In that situation, we couldn’t just leave the visiting PA people unattended. Uchii was often at LIQUIDROOM, so I’d watch him, and at first, I honestly thought, “Is he okay?” (laughs). At that time, I was doing PA for Audio Active* as well, so there was also a connection there. Listening to Uchii’s PA work for DRY & HEAVY, I thought, “He’s probably not getting it exactly how he wants it.”

*Audio Active: A dub band that has been active since 1987. In 1993, they recorded under the production of Adrian Sherwood, and in 1994, they performed at the UK’s largest rock festival, Glastonbury Festival.

DMX: At events like battle-of-the-bands or festivals, the difference in sound is brutally obvious. It’s really different. I mean, the sound systems are the same, but when the sound is blasted out, the difference in skill is immense. I truly think it’s terrifying.

Uchida: Exactly. So, when Audio Active and DRY & HEAVY toured together, I would ask Sasaki-san tons of questions at after-party izakayas. The things I learned from him have really become a part of who I am today. DRY & HEAVY’s first proper live performance was at LIQUIDROOM, so Sasaki-san and everyone from Acoustic feel like family to me. I was thoroughly taught by them—Sasaki-san, Takeda-san, and Taruya-san. I owe them so much. When I was young, I watched their PA work like crazy. Sasaki-san taught me two really important things.

DMX: Oh really?

Uchida: It’s about the mic preamp (the equipment that amplifies the sound captured by the microphone) settings and how to use the EQ (equipment that adjusts the sound frequencies). I still stick to those principles today.

DMX: The late Ono-san also told me when I was struggling at a gig, “Miyazaki-kun, you should handle this area like this.” The people from Acoustic, they would say, “This guy has potential,” and would give me some advice about PA here and there.

Sasaki: Maybe they only tell people they feel a connection with [laughs].

DMX: Hahaha! Well, we’ve all been through our own mistakes in the past, so we know better.

INDEX

What Makes Good Sound?

Earlier, you mentioned that “you can usually tell when someone is creating sound in a pyramid shape.” What do you all consider good sound?

Sasaki: Hmm, it’s hard to describe. But everyone definitely has their own sense of it. They’ve solidified it within themselves.

DMX: I don’t know… maybe it’s the texture? Like when you dry off with a towel after a bath, you might think, “This towel feels good, but this one doesn’t,” something like that. It could be similar.

Sasaki: Everyone’s ears are different, and even with volume, some people may find it comfortable, while others think it’s too loud or too quiet. Sound is a very abstract thing, right? But after doing this for so long, you start to understand the “pressure” that the body feels, like where the right volume should be or what feels comfortable. Most of the time, it’s about working to bring the sound to that point. The best thing is when both I and the audience feel good. But there are various patterns, like “I feel good, but the audience doesn’t,” or “The performers think it’s good, but I don’t feel the same.” Over time, these things start to align, and it becomes, “If I feel good, then everyone else will too.” That’s always what I aim for. If I feel good, then it should be good for everyone. It’s about refining that process.

DMX: For me, it’s more like, “I don’t know if it’s good or bad, but I did my best and that’s it.” Recently, though, a lot of people from the audience have been coming up to the booth and saying, “That sounded amazing,” or “It felt great.” And when production people say, “It was great,” then I’m like, “Well, that’s good to hear.” It’s like that. It used to be different, though. Back then, I thought, “I’m the best, I’m number one” [laughs].

Sasaki: Exactly! The ego really comes through in the sound [laughs].

Uchida: For me, “delicious” is a universal feeling for humans. Anyone eats Japanese food, the delicious things are still delicious, right? I want to aim for that kind of sound. I believe there’s a sound that anyone can listen to and think, “This sounds good.” I don’t have the answer, but it’s something I’m always exploring every day. There’s no prescription for it, though.

DMX: It would be great if we could just insert a “Ajinomoto” plugin into the master channel, right? [laughs].

INDEX

Contrasting Techniques and Mindsets

What is the role in live events and concerts?

Sasaki: PA stands for “Public Address,” which essentially means public broadcasting.

DMX: It’s about spreading the sound.

Sasaki: Generally, a PA engineer adjusts the volume and balance of the sound produced by the artist using a console, and ultimately, that sound is played through the speakers. For the artist, the sound they produce goes through the PA engineer’s filter, so it’s important to understand the artist’s intentions. In our company, we refer to this as “Sound Reinforcement” or SR, which focuses more on the sound itself. These roles are often collectively referred to as PA. Additionally, people like Dub and Ucchi are called “Dub Engineers.”

Uchida: That being said, I started doing this job without any knowledge, so in the beginning, it was full of accidents. Even though the equipment used in recording and PA is the same, the methods are completely different. In fact, the approaches and thinking are almost the opposite. Without knowing that, I was operating the console like I would for a recording session, which led to all sorts of accidents. I started completely self-taught, without even mastering the basics.n, with no basic skills at all.

What do you mean by “accidents” in the context of a PA setup?

DMX: Feedback. When feedback occurs, you can only cut that point out with the EQ.

Sasaki: You don’t understand those things at first. I was at a company, so I was taught the basics before going into the field. But with PA, it always starts with tuning the speakers. There are a lot of critical points in that process, and if you don’t know them, it can be a problem. When you start with recording, you miss that step.

Uchida: Since I started PA without knowing that, when feedback occurred, I was in a state of “I don’t know where it’s going wrong” and ended up panicking, thinking, “Oh no! Oh no!” [laughs].

DMX: There were a lot of times when it felt like walking a tightrope. It was scary to take the “all mute” button off on the console. Just before a live show starts, when you remove the all-mute button and noise comes out, you’re like, “What do I do!” [laughs]. But looking back, I wonder why there was so much feedback back then.

Sasaki: Nowadays, there’s much less feedback. The performance of speakers has improved, and the initial setup is significantly better than before. To be honest, even an amateur can get a decent sound now. Also, back then, there weren’t many well-equipped live houses in terms of acoustics. PA at clubs when doing live shows was difficult too. The speaker placement and the overall sound design were completely different from live houses.

DMX: PA at clubs was tough! People like San-chan, who were in PA companies, didn’t start out being told, “What the hell are you doing, causing feedback!” They worked under senior people. For me, just like Ucchi, it was self-taught. I’d ask experienced PA people, “How do you do that?” and they’d tell me, “Figure it out yourself,” and then I’d end up causing accidents. That’s how I learned.

INDEX

The Appeal of Analog Consoles: Insights from the Three Experts

To get back on track, “Dub PA” seems to require not only the basic techniques and knowledge of PA, but also a musical sense. It’s about applying effects in real-time to the band’s performance, creating acoustic effects.

Sasaki: Exactly, dub itself wouldn’t exist without analog consoles. With an analog console, moving the knobs and faders makes the sound change exactly how you envision it. There are actual effect devices within reach, and you can experiment with sound. But with digital consoles, once you press a button and select something, that’s often all you can do. So when you try to do dub on a digital console, it’s like applying pre-set effects during the song. I don’t think that’s dub. Dub is about doing things on the spot, things that you can’t anticipate.

As the times have changed, fewer live houses maintain analog consoles, and now digital ones take the lead. The reasons include the number of inputs and outputs, the integration with speakers, and the convenience of maintenance, among others.

Sasaki: Yeah. So when I did PA at WWW, I was actually a bit excited. The Heritage 3000 at WWW is an analog console.

Uchida: Nowadays, when I need to do dub, I bring my own 16-channel analog mixer to the live house. With only a digital console, I can only use two or three effects at a time. I set up the part I want to apply effects to on my analog console, and return about 8 channels of effects. The equipment I bring to the venue has increased, but it’s becoming a standard setup.

DMX: The other day, I went to do PA at Star Pine’s Cafe in Kichijoji, and they had a SOUNDCRAFT analog console, the MH4. As soon as I walked in and saw it, I thought, “Wow, I didn’t expect so many knobs!” While fiddling around, my fingers started to hurt (laughs). And sometimes while operating, I’d forget which knob I turned up, and think, “Is there too much reverb?” That’s the thing with working with analog consoles, it’s fun, even with the accidents.

Uchida: Yeah, but they’re still really easy to use. What I look for in a PA console is ease of use and clarity. It’s really helpful when you can easily do what you need to do.

Sasaki: That’s the most important thing. Then there’s the sound quality. But as long as it has the minimum sound quality needed, that’s fine. There aren’t that many different kinds of consoles out there. When it comes to PA consoles that professionals use, in broad terms, it’s SOUNDCRAFT, MIDAS, and YAMAHA for analog desks. Each brand has its own characteristics, and it’s about finding which one works best for you.

DMX: There’s a debate about sound quality differences between manufacturers, but I’ve never really cared about that.

Sasaki: Yeah, me neither.

DMX: For me, ease of use and weight are more important. When you’re on a tour or something, you start to think that lighter is better. When you’re setting up a console in a hall, there are times when you can only carry it to the aisle, or even not that far. Then you end up having to carry it all the way from the front of the stage to the back of the audience. It’s a nightmare. So, for me, it’s all about the weight. Honestly, I can handle a console with 16 faders if it’s light enough.

INDEX

Heritage is the King of Analog Consoles” (DMX)

As we discussed earlier, it’s becoming increasingly rare to see an analog console in use, and now the Heritage 3000 at WWW is “graduating.” In fact, the Heritage 3000 at WWW might be the only one of its kind in a live venue in Japan. What are your thoughts on the Heritage 3000?

DMX: I was away from the PA world from the 1990s to the mid-2000s, so I missed the rise of the Heritage series. During that time, the digital console era had already started, and I felt like a fish out of water. I first started using the Heritage after returning to PA, at a time when about a third of live venues still had analog consoles. I remember seeing Heritage consoles at UNIT and LIQUIDROOM.

Sasaki: The Heritage series was a huge hit worldwide. The MIDAS Heritage series and the YAMAHA PM series were pretty much the two big choices.

DMX: The PM series was quite common when I started in PA. CLUB QUATTRO in Shibuya, where I frequently worked, had a PM. The Heritage is a console from a British manufacturer, so it was more expensive than the domestic models. It had this aura of needing a big venue or a proper setup to use it. So, it’s definitely the “king” of analog consoles.

Sasaki: Personally, I find the Heritage the easiest to use. With analog consoles, the order in which the PA engineer adjusts the knobs is pretty standard, and once you understand how to use one channel, they’re all pretty much the same. Gain knob at the top, EQ knob, AUX knob, fader, etc. But the Heritage makes it especially clear. The entire signal flow is laid out right on the top panel.

Uchida: I started doing PA at LIQUIDROOM, so the first PA console I used was a MIDAS. Back then, they had the XL4 as the permanent setup. That was before the Heritage series came out, the earlier MIDAS model. Also, the console at the first recording studio I worked at was an SSL (Solid State Logic). The diagrams for the SSL and MIDAS consoles were pretty similar, so it was easy to understand.

Sasaki: MIDAS has always had a reputation for thick, solid sound.

Uchida: It probably has something to do with the quality of the mic preamps they use.

Sasaki: That’s likely. Also, the EQ feels great. There’s something about it that really “hits.”

DMX: The EQ works in a way that says, “You get it.” Also, the faders on the Heritage are fantastic. When you’re using the Heritage faders, it feels like the sound is sticking to your fingers.

Sasaki: Yeah, the way it moves up and down… wait, that’s too detailed of a point [laughs]. But, ultimately, the fader is what the PA uses to deliver what they’ve received from the musicians, so it’s important. That being said, personally, I really like the faders on Avid’s digital consoles—they’re very sensitive, and that’s a good thing.

DMX: I really like the faders on the SOUNDCRAFT digital console at WWW X. It’s kind of loose, like “0dB doesn’t even show up,” but that’s just right for me. Even the EQ curves are kind of rough. For a digital console, it has this analog-like, thrown-together feel [laughs].

Uchida: I never really thought much about the faders. I haven’t felt much difference in the touch… sorry about that [laughs]. But I do like the AUX knobs. On the Heritage 3000, the AUX knobs are arranged in two horizontal rows. I only use one row, but I find them personally easy to adjust.

DMX: I have trouble with them because my fingers don’t fit [laughs].

There was a mention of the good sound quality of mic preamps, but the equipment used in recording studios and the gear used in live sound setups, including consoles, are quite different, aren’t they? Is there a specific reason for that?

Uchida: If you use a recording-quality mic preamp live, it might end up being a bit too loud, don’t you think? Is that not the case?

DMX: Hmm, I’m not sure. There are actually a lot of people who are particular about incorporating recording equipment into their PA systems. I’ve had to work with that kind of setup sometimes, but for me, it’s like “so what?” [laughs]. If someone likes it, then they should use it, but for me… it’s more about whether the person is in the right mindset when they use it. I think that’s the main point.

Sasaki: If we go down that road, it would turn into a discussion about being particular about “power cables” or something like that. But basically, if the gear is in good condition, there’s no real urge to use recording equipment specifically. It’s more like, “If it’s a MIDAS, that’s fine,” or “If it’s that console, then I’ll bring that one.”

DMX: It’s not just with mic preamps—if you use an analog compressor, the sound quality obviously changes. This guy (Sasaki) also uses a TUBE-TECH compressor for live sound, and it does change the texture of the sound, that’s for sure. If you like it, then you just have to use it.

Sasaki: For vocals and bass, yes. With analog gear, it’s not just the texture of the sound—it’s that you can touch it immediately. If it’s right in front of you, you can just turn the knob and change the sound instantly.