Recently released compilation of Cornelius’ ambient tracks titled “Ethereal Essence.” When discussing the announcement of its release, there was a surprising revelation.

Considering his albums like “夢中夢 -Dream In Dream” (2023), which explores ambient pop, his participation in “AMBIENT KYOTO 2023,” and the recent revival of ambient music, it might seem like a natural progression. However, Cornelius has maintained a cautious distance from ambient music.

In this article, we delve into how Cornelius, or Keigo Oyamada, has embraced ambient music and integrated its aesthetics into his unique sound design, influenced by minimal music. The interview, conducted with the former editor-in-chief of ‘STUDIO VOICE,’ Masato Matsumura, as the interviewer, was conducted in a relaxed atmosphere, following a discussion about their mutual friend, Masaya Nakahara.

INDEX

Born in Tokyo in 1969. Made debut in 1989 as a member of Flipper’s Guitar. After the band disbanded, started solo career as Cornelius in 1993. In June 2023, released 7th original album “夢中夢 -Dream In Dream-“. Participated in “AMBIENT KYOTO 2023” from October of the same year, releasing cassette work “Selected Ambient Works 00-23”. Celebrated 30th anniversary in 2024, releasing compilation “Ethereal Essence” centered around recent ambient-influenced works. Actively engages in collaborations, remixes, and productions with numerous artists both domestically and internationally.

Exploring Cornelius’ Approach to Ambient Music

-How did you come to produce ambient music as Cornelius?

Oyamada: We often created ambient music for corporate commercials, music for commercial facilities, TV-related music such as “Design Ah”, and web advertisements. In those occasions, there was visual information such as images, so there was no need to use music to explain the situation, and I really made it as background music.

-The cassettes on sale at “AMBIENT KYOTO 2023” included music from “POINT” (2001) onward, but do you have a clear sense of what came before or after “POINT”? Do you have a clear sense of what came before or after “POINT”?

Oyamada: Yes, I do. After “POINT,” I changed my basic style from time to time.

-I think you have changed little by little from there. POINT” and “SENSUOUS” (2006) are different, and “Mellow Waves” (2017) is totally different. The changes are a result of the feelings you had when you were making each one, right?

Oyamada: It could be the time period or my own situation.

-It depends on the time period and your own situation.

Oyamada: I feel like I’m always slightly aware of it.

-I feel that I have always had a slight sense of ambient sounds and minimalism in my music.

Oyamada: Well, you know… I think things like “serenity,” and also, the resonance of sound, the texture of the sound are important. With ambient music, it feels like texture comes to the forefront more than melody or rhythm. Even though this time I’ve compiled my ambient-like tracks, being originally a pop-oriented person, I still feel like the structure tends to be pop-like as I create it.

–Do you have much self-awareness that you are making ambient music?

Oyamada: I don’t think it is pure ambient music.

INDEX

Keigo Oyamada with Environmental Music, Ambient House and New Age Revival

-What did you think of ambient music before this?

Oyamada: First of all, Brian Eno, right?

– “Ambient 1: Music for Airports” (1978), the starting point. When did you first hear it?

Oyamada: I was in my mid-20s when I heard “Ambient 1: Music for Airports” by Eno.

-Were you conscious of so-called “environmental music” in this “Ethereal Essence”?

Oyamada: I knew and listened to Hiroshi Yoshimura with “Kankyō Ongaku.

-The title of “Kankyō Ongaku” is in Japanese, but I sense a foreign perspective in your sense of song selection.

Oyamada: It might be. When I was in junior high or high school, I used to listen to Penguin Cafe Orchestra, and back then, they were called “environmental music,” right?

-Yes, they were.*

Oyamada: That was the image of the Saison Group, and also Haruomi Hosono’s “Hana ni Mizu” (Water for Flowers) at MUJI, and in the 1980s, Erik Satie was a bit popular, and there was a world and ambient section on the first floor of Roppongi WAVE, and that kind of thing.

In “Wave Notation: What is Environmental Music? Satoshi Ashikawa, a musician featured in “Kankyō Ongaku,” describes his “wave notation” as an extension of Erik Satie’s “furniture music” and Brian Eno’s “ambient series,” and describes his concept as “the whole of what I am trying to do is, in a large sense, ‘sound The whole thing I’m trying to do can be called ‘sound design’ in the larger sense of the word. Sound design” means creating an environment that emphasizes the relationship between humans and sound/music” (quoted on p. 24).

-Did you also listen to minimal music back then?

Oyamada: No, I didn’t listen to it. But back in the New Wave era, there were things like “Les Disques Du Crépuscule” that had elements close to minimal music, so I listened to those. In the vein of “Obscure Records,*” there were artists like Michael Nyman and also Wim Mertens. The Durutti Column, although not called ambient back then, has a vibe that feels somewhat similar if you think about it now.

※ It was a label founded by Brian Eno. They released works such as Brian Eno’s “Discreet Music” (1975), David Toop and Max Eastley’s “New and Rediscovered Musical Instruments” (1975), and works by Gavin Bryars, Michael Nyman, Penguin Cafe Orchestra, Harold Budd, among others.

-So it was that kind of listening experience that nurtured your view of ambient music.

Oyamada: When I was in junior high school and high school, I liked new wave and punk music in real time or a little before, and I listened to what Cocteau Twins did with Harold Budd.

The ambient boom in the 1990s was centered on club music like The Orb and The KLF, but there was also a lot of ambient music like Julie Cruz and “Twin Peaks” that I liked. I think the ambient music of the 1990s was mainly club music like The Orb or The KLF, but I also felt that the cold, reverb-heavy, spacey, dream-pop sound of Julie Cruise or Twin Peaks was in sync with the ambient music of the time.

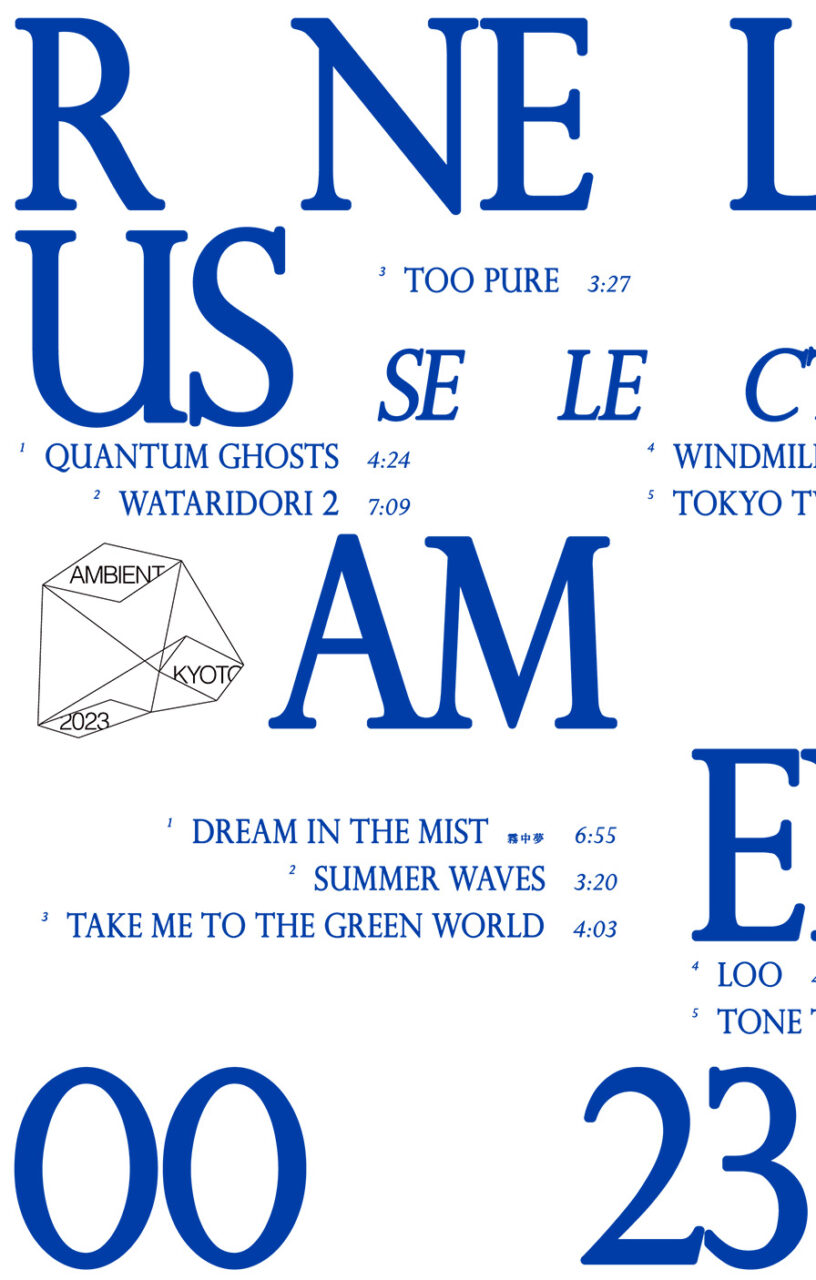

-The title of your cassette is based on Aphex Twin’s “Selected Ambient Works 85-92,” which was released in 1992.

Oyamada: There are beats in it, too. There was a strong influence of house music and rave culture at that time, and the ambient revival of the 1990s like “Chill Out” (1990) by The KLF, which was about “dancing till morning and chillin’ out,” and the environmental music of the 1980s were in completely different places. The 1980s was a little more relaxed.

-Did you have the same feeling as you just analyzed?

Oyamada: I think it was because of the passage of time. I was listening to many other things at the time.

-Ambient music also has a different taste, from the environmental music of the 80s to the club culture of the 90s represented by Aphex Twin, The Orb, and others, to the completely different and shifting styles of the 2000s and beyond. The ambient music that is popular today has a bit of a new age feel, doesn’t it?

Oyamada: I feel that new age-esque music has become more common since the recent revival. There was a part of the music that had a slightly smelly image, but the direction of the music has changed.

In the first place, ambient music and spirituality are inseparable, and I think there were a lot of things that came out that took advantage of that at the time, and I think there was some disenchantment with them. However, there were works that could stand the test of time, and I think young people and people overseas responded genuinely to the sound, and that is why it became popular.

-I think it is possible to teach from the perspective of young people and people overseas.

Oyamada: Yes, yes. I knew Laraaji existed at the time, but when I listen to the sound recordings that were discovered back then with my modern ears, I find that they are really good.

-So your taste in sound and the way your ears perceive it have also changed.

Oyamada: Yes, my uncle is changing in his own way, too [laughs].

INDEX

The Turning Point: “POINT“

-Aphex Twin’s “Selected Ambient Works 85-92” was a favorite of yours at the time?

Oyamada: I listened to both the 1994 release (“Selected Ambient Works Volume II”), but I think I listened to it most around 1995 or 1996, when I made “FANTASMA” (1997). There was a song called “i” that I really liked because it was so floaty and I felt like I was drifting in space.

-I really liked it because it felt like I was floating in outer space. Did you listen to this kind of music in your private time while making it?

Oyamada: Yes, I did. It was around the time of “POINT” that I got into minimal music and ambient music for the first time.

-I think we’ve talked about this a few times, but did you have to assess your capacity for information?

Oyamada: That was part of it. Around the time of “FANTASMA,” in the late 1990s, it was said that the record industry was at its peak, and there was an overabundance of information, a state of chaos. Personally, I was also in a state of upheaval. After “FANTASMA,” I started touring overseas, and my living environment changed drastically.

I don’t know if it was coincidence or guidance, but I was in my 30s, got married, and had a child, so there were many things happening in my life cycle. It was at that time that I started to move in a minimalist direction.

-I guess I was just at the surface tension of the possibility of quoting something like sampling culture, or listening to a vast amount of music and creating something in response to it, not only in my head, but also physically?

Oyamada: Physically, yes, and I made “FANTASMA” by sampling and editing various music from records, but I ran into a clearance problem when releasing it overseas. This method was interesting, but I also felt that it would be troublesome to continue using it in the future.

-So you had reached a turning point in terms of rights. But the way of making music has changed since then, hasn’t it? Did you ever hit a wall there?

Oyamada: Not so much. New discoveries were more interesting. At the time of “FANTASMA,” we rented a rather large outside studio and paid 300,000 yen a day for the work, which is too scary when I think about it now [laughs].

But I remember thinking that I could no longer see the future with this kind of approach. Around that time, computer-based recording became almost possible even in a simple studio, and I shifted to that method. I guess it suited my nature.

-After that, you were able to check recordings on the screen as well, right?

Oyamada: Being able to see the audio and MIDI* data as images, and being able to say, “Let’s move this sound here,” was a big deal. In terms of post-production, I was able to change the way I made music and create my own unique style.

MIDI (Musical Instruments Digital Interface) is a standard established in 1983 for digitally transmitting performance data of electronic musical instruments. It refers to the control data for sound sources such as synthesizers, rhythm machines, and sound source software, and is also called MIDI tracks, MIDI files, etc. – see Rihiko Yokogawa, “Introduction to Sound Production: Basics and Practice of DAW (2021, BNN).

-How has your production process changed?

Oyamada: After “POINT”, I started to compose music in a way where I just kind of make a sound and see how I can approach that sound. Instead of thinking of a structure or melody and recording it, I would create small chunks of chords or instruments and develop them on the spur of the moment. Basically, it is a way of developing motifs while manipulating the time axis.

-It is a kind of generative method. What exactly do you mean by manipulating the time axis?

Oyamada: For example, with a tape, time flows only in one direction from the beginning to the end. With a computer, however, you can freely move back and forth along the time axis, such as reworking this side and putting this side and that side together. You can also redo the recording. The tempo is the first thing to be decided, but it can be changed later.

-So there is an improvisational aspect to your music?

Oyamada: In the past, there was almost no improvisation, but now there is a great element of improvisation. For music for TV or advertisements, even if we have a theme, we don’t always know what kind of music we are going to make, and we often think of it after going to the studio that day. For my own albums, I have an image of what I want the music to sound like.

INDEX

Eternal Innovation: Understanding Cornelius’ Unique Sound

-Did you feel any difference between the acoustic sensation of live band playing in the studio or sampling music and that of DAW-like music?

Oyamada: I really felt that. In creating music in stereo, I became conscious of a new parameter called “spatial arrangement” in addition to the elements of sound such as rhythm, chords, melody, and tone.

In a DAW-style production without microphones or amplifiers, air sounds are not included, so the localization of sound becomes clearer. But on the other hand, if you use only digital sounds, the sound is small, or the space is very small. In contrast to the digital sound, I felt the need to include acoustic instruments and human voices, which would bring a bit of air into the sound.

-What other changes did you make in the production process?

Oyamada: If sounds in close frequency range are pronounced at the same time, they will cancel each other out, so while checking on the screen, we tried to avoid producing sounds at the same time, and if we did, we tried to separate the low and high frequencies. This is also true for sounds like drones, which are always sounding.

By avoiding the placement of sounds and their frequencies, localization becomes clearer. In this way, the sound can be felt as a mass, and the sound itself can be felt.

-That is one of the rules and characteristics of Cornelius-like music after “POINT”, isn’t it? There seem to be other prohibitions in your mind, Mr. Oyamada.

Oyamada: Yes, there are. But I remove them when they become too much of a hindrance [laughs].

– In your case, you are willing to use mechanical functions and technology as long as it can be used. I think there are many people who avoid such things as aesthetics, but I don’t think you seem to have that attitude at all.

Oyamada: If I had to say, I wouldn’t say that. But I am indeed afraid of AI. Well, I’ll use it [laughs].

-I guess we are already talking about how to deal with AI, aren’t we?

Oyamada: That’s right. I don’t know how many years from now AI will dominate our lives, but until then, I think we will continue to have to deal with AI for a while. The era in which we can take the initiative will continue, and the era in which we can run side by side with AI-like things has already arrived, hasn’t it?

At the time of “POINT,” there were various subgenres such as post-rock, acoustic, and electronica, for example.

Oyamada: I wasn’t really conscious of doing electronica or post-rock in particular. I listened to a lot of electronica, but I consciously avoided putting glitchy sounds and other tones with a strong genre nomenclature in my works.

-So you are not talking about genres or formats as an idea.

Oyamada: I think it is, but it is still something close to something. Shintaro Sakamoto once said, “Perverts never get old.

-I think that’s a great saying.

Oyamada: I think that the more original something is, the more it transcends the times. If the image of the era is too strong, it will only be accepted as something unique to that era. For example, NEU!

-Yes [laughs].

Oyamada: Everything about NEU! is a method, a way of being, and a symbolism that feels like NEU! That kind of thing is strong, isn’t it?

INDEX

Seasonal Culture, Sound Design, ASMR, and Hugo Zucarelli

-When we spoke the other day, you mentioned that “Ethereal Essence” is like Haruomi Hosono’s “COINCIDENTAL MUSIC” (1985). I think that various orders like that open up new ways of creating your own sound.

Oyamada: That’s right. It gives me a chance to open drawers that I normally don’t open, to see what kind of approach I can take to an order, and it is a chance for me to discover that “this kind of thing is possible,” or “this kind of thing is interesting. For my own work, I have to come up with my own themes, so if anyone has any ideas, I’d like you to think of them [laughs].

-The second song, “Sketch For Spring,” is the background music for the opening of Shibuya PARCO, which is also on the cassette.

Oyamada: A little while ago, I was selecting background music to be played inside PARCO, and I made one song for each season, selecting songs for spring, summer, fall, and winter. In spring, this song is played once every few hours, mixed with songs by various artists I selected. At this time, I also made the closing music and the time signal.

-So you are involved in Saison culture in a concrete way.

Oyamada: The current PARCO staff grew up with Saison culture, so I wanted to keep the Saison spirit alive. They invited Mr. Ukawa (Naohiro) to hold DOMMUNE as “the last cultural stronghold in Shibuya,” and there are people who have that kind of spirit. I was also a child of Saison, so I was very honored to be asked to be a part of this project.

-This song was rather close to Oyamada’s field of work. Like “Design Ah”, this kind of cross-media expansion is an important point to consider for “Cornelius in the 21st century”. When we talk about “design and music” or sound design, Cornelius is the first name that comes up.

Oyamada: It is true that people say that sound design is something that everyone does.

-I think sound design here means placing as much importance on sound resonance and texture as melody and harmony.

Oyamada: I think that’s what everyone is thinking about, too. But perhaps not many people recognize music as “something that arranges sounds within a space and time axis. Of course I think about lyrics and melody, but in my case, I always focus on that when I formulate a piece of music.

-Do you remember the “holophonic sound”? When I was a student, there was an ad in Gakken’s “Mu” magazine, I think it was, on the front or middle page, and I mail-ordered a cassette tape that claimed to have “Holophonic Sound”.

Oyamada: Was it Hugo Zuccarelli? I heard him at the listening machine on the first floor of Roppongi WAVE. It was the kind where the sounds of hair cutting and hair dryer application were so realistic that it was a bit like an optical illusion. I didn’t know they sold them in “Mu” [laughs].

(Laughs.) But I heard that they didn’t reveal how they were able to make the recordings so realistic. Hugo Zuccarelli is a great guy, and he’s done work with Michael Jackson, Lou Reed, Pink Flyold, and there’s sound in Psychic TV’s “Yu Words of the Temple” (1982’s “Force the Hand of Chance”).

-You are strangely knowledgeable.

Oyamada: I did a lot of research at the time (laughs). (laughs). I went out to buy it with Masaya Nakahara. Under his influence, we used dummy heads and binaural recording* for “FANTASMA.

Binaural recording is a stereo recording method in which omni-directional microphones (which pick up sound equally in all directions) are attached to a dummy head (mannequin’s head) or to both ears of a person. Eisuke Yanagisawa, “Introduction to Field Recording: Encountering the World in the Sound of Sound” (2022, Filmart-sha), p. 19 (in Japanese).

-That was a shock. I was taught the fun of “sound that is not music” when I was a teenager.

Oyamada: It was that kind of experience.

-I think it was something like what we now call ASMR.

Oyamada: In the sense of the pleasantness of the sound of reality, it’s completely in that vein.

-For “Forbidden Apple,” you are aware of ASMR, aren’t you?

Oyamada: Yes, I am. That’s why Hugo Zuccarelli is in it [laughs]. I wonder why the sound of an apple being nibbled on feels so good.

-The sound of biting an apple is very symbolic, but it has a sonic complexity. Is that sound a library source?

Oyamada: Yes, it is.

INDEX

Ryuichi Sakamoto’s Song Sympathy with Cornelius

-What about “voice”? I think the Cornelius version of ASA-CHANG’s “Confession” is a song that strikes a surprising chord.

Oyamada: There is a filmmaker named Kazumasa Teshigahara, and ASA-CHANG read his profile and found it so amazing that they wrote the song using a soundtrack of a girl reading it out loud.

-So Teshigahara himself is an important point.

Oyamada: By coincidence, Mr. Teshigahara was one of the artists who created a video for the “AUDIO ARCHITECTURE: Sound Architecture Exhibition” at 21_21 DESIGN SIGHT in Roppongi. He is a wonderful abstract and psychedelic filmmaker, but I heard that he grew up this way (laughs).

-I think the human voice is a very mysterious instrument. Shuntaro Tanikawa’s “Here” also reminds me of this.

Oyamada: I wrote this song for Tanikawa Shuntaro’s exhibition. I asked Tanikawa to recite his own poems, analyzed each note of his recitation, applied it to the Do Re Mi Faso Rashido scale, and then harmonized the notes to that scale. I used Melodyne, a pitch correction software, to decide on the chords and melody.

In Steve Vai’s first album, there is a song that Frank Zappa wrote by handing a conversation to Steve Vai and saying, “Copy this conversation on the guitar. In Steve Vai’s case, he used his own ears and guitar technique, but even though he uses mechanical power, the idea of capturing the human voice by converting it into a musical scale is similar.

Do you have a strong self-awareness as a vocalist?

Oyamada: Not really. If I could get someone else to sing, I think the music would become something else, but since I do my own live performances, it’s too much of a hassle to ask someone else to sing every time. I am not good at singing at all, but nowadays machines are so advanced that even I can manage.

-I don’t know whether to be passive or active.

Oyamada: Well, it’s both [laughs].

-What about the cover of Ryuichi Sakamoto’s “Thatness and Thereness” that closes the album?

Oyamada: Because it has more weight when it’s in the middle of the song.

-Koyamada: It’s a song that has a lot of weight to it when it’s in the middle.

Oyamada: When Mr. Sakamoto was still fighting his illness, we covered this song for a tribute (“A Tribute to Ryuichi Sakamoto – To the Moon and Back,” released in 2022) that we made together on his birthday, with the hope that he would get well. I like the song simply because I like it. I chose this song not only because I like it, but also because I wanted to play a song that Sakamoto-san sings.

Do you like Sakamoto-san’s vocals?

Oyamada: I really like it. I like the simplicity of it.

-I like the simplicity of your vocals.

Oyamada: Yes, yes. The songs are very simple, and I like the way they are sung in a simple way.

-The contrast is fascinating. For example, there are many different types of ambient music, and I think Sakamoto’s sound is the exact opposite of the simplicity of new age music. On the other hand, your songs are extremely simple.

Oyamada: In the case of Mr. Sakamoto, his music is different from that kind of simple music, because he also composes the sounds properly. I think it would be a shame to have your music be lumped in with the “it feels so good” type of music. I think the spirituality of the music is another reason for the resistance.

-I think that is the root of your resistance, too.

Oyamada: I do have a sense of resistance to being oversimplified.

INDEX

Towards an Unseen Peak: Reflections on Midlife and YMO

When we talked about Haruomi Hosono recently*, you mentioned that Sketch Show became an opportunity for the three members of Yellow Magic Orchestra to reunite. At that time, did it have aspects like being a vessel for cross-generational collaboration in ambient and electronica genres?

Oyamada: Sketch Show was the catalyst for me to join the three of them. I don’t know if I should be included, but I think there was something in that music that certain people could share back then. It had been quite a while since Mr. Sakamoto had joined up with those two, and it had been quite a while since Mr. Hosono and Yukihiro had been in a band together to begin with.

*Interview in “Yukihiro Takahashi: Music Ikijin no Zenpo” (2024, Kawade Shobo Shinsha)

-Sketch Show itself had a spontaneous aspect to it. What were the things you shared?

Oyamada: In terms of music, I think it was a “minimal, delicate” kind of element. Also, in the early 2000s, there was the 9.11 incident, and times were changing a bit from the competitive side.

In the 1990s, Sakamoto was playing house in New York, and electronica is close to the context of minimal music and contemporary music. In the case of Hosono and Yukihiro, I think their folk-like delicacy had a strong affinity with electronica. I think that in the case of the three of us, we were able to arrive at electronica from a variety of different contexts.

Oyamada: I think there is also the age factor: between Sketch Show and the re-formation of YMO, in the mid-2000s, Hosono-san was around 60, and Sakamoto-san and Yukihiro-san were a little younger than I am now, around 53 or 54. So, in terms of lifecycle, they have settled down once.

-I guess there were a lot of coincidences in terms of music, time period, and life cycle of each of us.

Oyamada: In the 1990s, when YMO got together again, all three of us said at the time that it was a bad idea to be business-driven because there was not much we could share. Compared to that time, we now genuinely share music and eat dinner together.

Looking back on it now, I think all three of us were still young, but we started talking about “getting old. I was talking about quitting smoking and so on. So I would like to talk with them as they are now, because I am a newbie to the geriatric world (laughs).

-What do you think about getting old, Oyamada? Should I wither away from now on?

Oyamada: I don’t know. It is really difficult, this first aging problem [laughs].

-During the time of “POINT,” I remember being interviewed by Yuichi Kishino*, and you mentioned feeling a sense of “wabi-sabi.” Perhaps Keigo Oyamada had reached that state at a young age.

Oyamada: No, of course I was conscious of it in some aspects, but it was just the wabi-sabi of a young man in his 30s (laughs). Sakamoto-san’s “out of noise” (2009) and “12” (2023) have a very wabi-sabi feel to them. Compared to those works, mine are still very childish [laughs].

-It is not truly a source of physical deterioration.

Oyamada: I think they are completely different dimensions.

*Referring to an interview that appeared in the November 2001 issue of “STUDIO VOICE” magazine, “Special Feature: The New Century of Post-Techno/Electronica.

-I think there is a reality in that.

Oyamada: But I think there is a reality due to that.

-Sakamoto-san, your works after “out of noise” are very good.

Oyamada: I love it.

-I think it was a challenge to the very end. I think it was challenging right to the end.

Oyamada: Yes, yes.

-Given the fact that you are a musician, I think you have a long way to go before you reach your peak.

Oyamada: I hope so.

Cornelius

Ethereal Essence” (CD)

Released on Wednesday, June 26, 2024

Price: 3,300 yen (tax included)

WPCL-13566

1. Quantum Ghost

2. Sketch For Spring

3. Heaven Is Waiting

4. Too much like sauna, more deeply

5. Xanadu

6. Xanadu

7. Step Into Exovera

8. Forbidden Apple

9. Melting Moment

10. Confession – Cornelius ver.

11. Mind Matrix

12. Windmills Of My Mind

13. Thatness And Thereness – Cornelius Remodel

Cornelius

Selected Ambient Works 00-23″ (cassette)

Friday, October 6, 2023

Price: 3,410 yen (tax included)

[Side A]

1. Quantum Ghosts

2. Wataridori 2

3. Too Pure

4. Windmills Of Your Mind

5. Tokyo Twilight

[Side B]

1. Dream in the Mist

2. Summer Waves

3. Take Me To The Green World

4. Loo

5. Tone Twilight Zone