Filmmaker Oda Kaori reflects on the completion of her film “Thus a Noise Speaks” (2010), which focused on herself and her family: “I couldn’t find any more messages I wanted to convey within myself. At that point, I could have stopped making films.” However, Oda has ultimately not let go of filmmaking, because she believes there are voices she must share through her work, and that there are those in the distant future who will receive these voices.

After studying for three years as a first-year student at “film.factory,” led by Hungarian director Béla Tarr, Oda ventured into Bosnian coal mines 300 meters underground and a spring in Mexico where sacrifices were reportedly made. In her new work “Underground”, Oda focuses on the underground world of various locations in Japan. In light of its release, she reflects on her journey, her thoughts on “camera ethics,” and her motivations for filmmaking.

INDEX

From Basketball to Camera: A Journey of Transformation

To start, could you tell us a bit about your journey? You’ve mentioned in several interviews that you played basketball from elementary through high school. It sounds like you were pretty serious about it.

Oda: Yes, I started playing mini-basketball around 4th or 5th grade. I’m not one to boast, and I wasn’t particularly great, but in middle school, I made it onto the Osaka prefecture team, and in high school, I was aiming for the national sports festival.

Born in Osaka Prefecture in 1987, Kaori Oda is a filmmaker. She graduated from the Film Studies program at Hollins University in 2011. Her graduation project, the short film Thus a Noise Speaks, won the Audience Award at the Nara International Film Festival. In 2013, she joined the first cohort of film directors in film.factory, a program led by the renowned filmmaker Béla Tarr. Her feature films include Mineral ARAGANE (2015), which focuses on a Bosnian coal mine, and Cenote (2019), which explores an underground spring in Mexico. Her latest feature, Underground, will be released on March 1, 2025.

Did you ever consider continuing as a basketball player?

Oda: I knew I wasn’t going to be an Olympic athlete, but I thought I’d probably continue basketball by joining a company and playing in a corporate team. Basketball was my whole world, so it felt inevitable.

But in my first year of high school, I tore a ligament, went through rehab, tore it again, and eventually couldn’t run anymore. At that point, I wasn’t that passionate about basketball anymore. It wasn’t just because of the injury; it was because the coach at my high school was very violent. If you made a mistake, it would lead to violence, so I just thought, “I’ve had enough,” and walked away. I was kind of brainwashed at that time.

What made you choose Hollins University in the U.S. for your studies?

Oda: I think I had a feeling of wanting to escape as far away as possible. In high school, I was in a dorm, and everything was confined to the campus. You weren’t allowed to have a cellphone, and the access to information was limited, so I wanted to know what was beyond the campus.

Also, there was an English teacher who had talked about her experiences abroad during class. Her stories were interesting, and I think that left a positive impression on me—like, “That sounds great.”

So you started preparing for entrance exams after that.

Oda: Yes. We entered high school on a sports scholarship, so as long as we won games, we could sleep through class without getting into too much trouble. I didn’t study at all. But when I stopped playing basketball in my second year, I thought, “What should I do now?” and decided to study English. Before studying abroad, I attended a short-term program at Kansai Gaidai University, although I didn’t learn much. Still, I studied foreign languages for two years, and then transferred to an American university.

What made you choose the Liberal Arts Film Program at Hollins University?

Oda: When I couldn’t play basketball anymore, I thought that whatever I did next, it should be something I could do for the rest of my life. I told the person helping me with my study abroad plans that I wanted to try drawing or using a camera. But they said it would be difficult to go to an art school since I didn’t have a portfolio. So, I applied to Hollins University, where they had classes that involved working with cameras.

When I started university, the first equipment we used in class was a Bolex film camera and DV tapes. Given my generation, it was a big deal that there were already machines where you could press a button and start recording. I remember thinking, “If I press this red button, I can at least start recording.”

INDEX

Avoiding the Transformation of Subjects into Convenient Narrative Characters

Did you watch many films as a spectator before you started shooting?

Oda: There was no habit of going to the cinema in my family or among my friends. I feel like my original experience with film came more from the making of Thus a Noise Speaks (2010) than from watching movies.2010) than in viewing.

That’s the film you directed as your graduation project at Hollins University, right?

Oda: Thus a Noise Speaks was a project I shot after a teacher advised me, “If you don’t know what to shoot, capture the most conflicted aspect of your life right now.” In that, I communicated my sexual orientation and gender identity to my family. But once that chapter seemed closed, I felt like there was no more message within me that I wanted to convey.

At that point, I could have stopped making films. However, through the production of Thus a Noise Speaks, I confronted the violent potential of the camera, while also sensing its potential as a communication tool. I began to think that maybe I should hold on to that possibility a little longer.

Even if I had no message to express personally, I started to shift my perspective, realizing that I could use film to explore unfamiliar worlds or things I wanted to understand but couldn’t.

How did your personal filmmaking style evolve after that? Your films often feature the camera moving freely in all directions, and there are many poetic and abstract scenes. Watching them, I get the sense that the film is challenging the audience, asking, “How do you feel about this?” in a positive way.

Oda: When I’m filming, my focus isn’t so much on how I want to shoot, but more on the ethical question of how to use the camera without intentionally causing harm to the subject. This way of thinking started after I had the experience of directing Thus a Noise Speaks and turning the camera on my own family.

I’m curious to hear more about the ethics of using the camera. In your past work, what specific considerations did you have?

Oda: For example, in ARAGANE (2015), there was a moment when the subject briefly mentioned labor conditions. I made a conscious effort not to consume that information or pretend to understand it.

Oda: When it comes to coal mines, the common topics that come up are often “dangerous jobs” or discussions about how harsh the working conditions are. I started to wonder if that’s what I originally thought as well. If the goal is to convey the labor environment, then that’s fine, but if you try to capture it with a voyeuristic mindset when that’s not the intent, I think it ultimately backfires.

I believe there are limits to what I can convey with the skills I have at that time. If I tried to push beyond that in the film, I think distortions would inevitably arise, both for me and for the subjects involved.

I make sure not to cut out topics that I can’t take responsibility for.

Oda: I’m conscious of not consuming or creating a narrative ourselves. The truth is, we don’t really know. Even if I’ve spent six months researching, I can’t understand the experiences of someone who’s worked there for 30 years. I made sure not to pretend I understood or spoke on their behalf. Moving forward, I think it’s important to consider whether I can truly take responsibility for the film as long as it’s being shown, even after I’m gone.

Editor Asai: Watching your works, I personally understand the sense of “not creating a story.” At the same time, I also believe that stories have a certain power. How do you perceive the line between these two?

Oda: I definitely believe that stories have power. I think that by fitting things into the structure of a story, some things can be communicated more effectively. While I’m conscious of not making it a narrative that suits my own convenience, I feel that, as part of a fictional element, borrowing the structure of a story might become more common for me in the future. Stories have a shared space, don’t they? I hope I can make good use of that.

INDEX

Collecting Words as a Vessel of Memory to Deliver Messages to a Distant Future

It seems like you really prioritize research and preparation before filming.

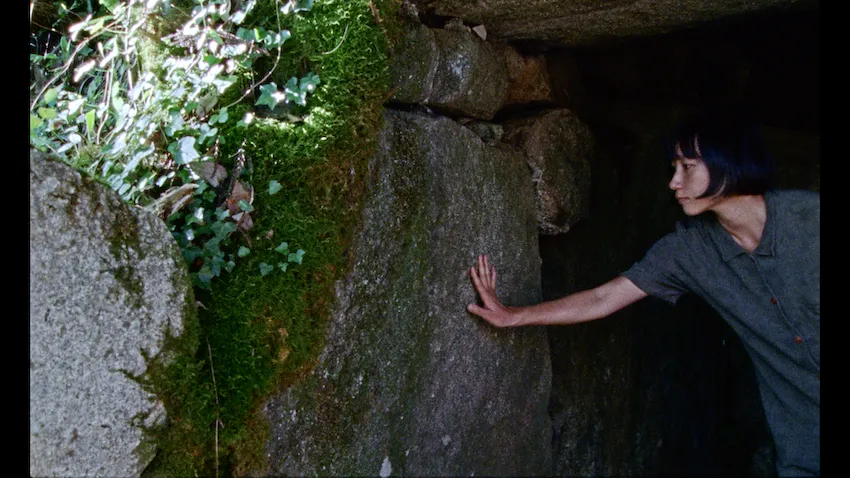

Oda: I believe some things can be captured on instinct, but there are also things that, without the right approach, I wouldn’t be able to shoot. However, with enough research and time, I feel I might be able to capture them. The filming I did in Okinawa for GAMA (2023) and Underground (2024) is a perfect example of that.

What kind of time did you set aside before starting the filming in Okinawa?

Oda: At first, one of the producers and I were guided by Mitsuo Matsunaga, who continues his peace guide and bone collection activities in Okinawa. We visited quite a few caves (Gama) where many residents lost their lives during the Battle of Okinawa. During that time, I experienced Matsunaga’s storytelling as well. I think it lasted about a week.

Afterward, I went to Okinawa again with Nao Yoshikai, one of the cast members of Underground, and an assistant. We visited several caves and U.S. military bases. Then, I had all the staff involved in the film experience Matsunaga’s storytelling in Okinawa before we started the filming period.

Oda: Up until now, I’ve mostly participated in projects as an outsider, and I think the same can be said for Okinawa. In addition to being an outsider, I also recognize that I am part of the oppressor side when it comes to Okinawa. It might sound extreme to say “oppressor,” but living and working in Osaka, outside of Okinawa, I am undeniably part of the group that imposes things.

As a citizen, I also think we must not forget that structure.

Oda: I’ve always wondered whether I could create something without consuming or exploiting the story of Okinawa. But having Matsunaga-san there made a huge difference. Through him, through “Okinawa seen through Matsunaga-san,” I thought there might be something I could do. That’s how GAMA came to be.

First, Matsunaga-san conveys the memory of Okinawa through his narration, and then you, Oda-san, record and share that story through your film with the audience.

Oda: Matsunaga-san, who did not directly experience the Battle of Okinawa, uses himself as a vessel to pass on the memories and stories of others. I thought I might be able to contribute to that in some way.

I’m 37 now. If I live another 37 years, I’ll have time to make a few more feature films. In thinking about what legacy I want to leave, I know I want to express my own feelings, but more than that, I want to pick up the words of those who have so much to say. That’s what I feel I want to focus on now.

You actively try to capture not only humans but also non-verbal creatures. In your past works, we’ve seen the presence of cats, birds, cows, fish, cockroaches, fleas, and spiders. How do you think about the memory of such beings?

Oda: I don’t think we can truly imagine the memories of animals. But on the other hand, when you trace back through layers of earth, there are facts like “this lived” and “that lived.” In that sense, I think our collective consciousness and memory might reside in something from the eukaryotic era. So, I don’t consider animals and humans to be separate. I imagine we are on the same timeline.

In Cenote, the phrase “this is our story” is repeated, and in your new work Underground, there’s a symbolic moment where the singular “I” changes to the plural “we.” When you use the words “we” or “us,” it seems like you’re aware of that timeline, including the future without humans.

Oda: I intend to include that. Even if we no longer exist in human form, I believe something will still be here. I want to say, “You might have been part of us.” I am conscious of the feeling that the small films we’re making could survive and live on for a long time.