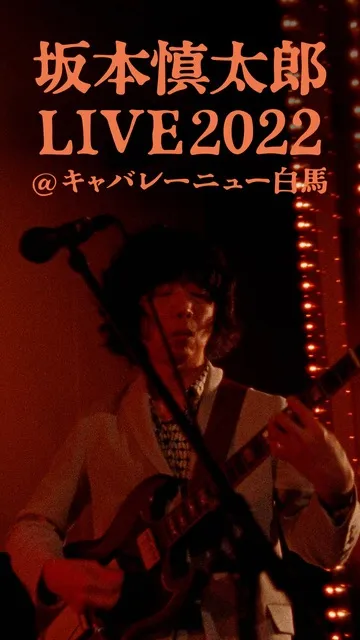

There are moments that demand to be preserved not just as memories but as lasting cultural treasures. For Hitoshi Ōne, director of Tokyo Swindlers and longtime collaborator of Shintaro Sakamoto, capturing the live performance of Sakamoto was one of those moments. The result is Shintaro Sakamoto LIVE2022 at Cabaret New Hakuba, a film shot on evocative 16mm film that premiered on Netflix on May 1, 2025.

Known for directing the iconic footage of Yura Yura Teikoku’s Hibiya Open-Air Concert, Ōne poured his passion and vision into this independent project determined to create something that would endure far beyond the night of the show.

In an exclusive interview with music writer Ryohei Matsunaga who also played a role in choosing the unique venue they explore the motivation behind the film the deliberate choice of 16mm and the deep bond between the director and the musician stretching back to the Yura Yura Teikoku days.

INDEX

“Preserving Shintaro Sakamoto’s Live Performance.” The Sense of Mission Carried by Hitoshi One

Let’s begin by talking about how the live shoot at Cabaret New Hakuba in Yatsushiro, Kumamoto Prefecture actually came to be. I was a bit involved in that from the very start.

Hitoshi Ōne: Yes, that’s right. It happened around January 2020. I had the opportunity to have dinner with Shoichi Kuroki, a Fuji TV producer who sadly passed away last year in 2024. You were also at that dinner.

Video director born in Tokyo on December 28, 1968. Known for his distinctive touch on late-night dramas like Tada’s Do-It-All House and the iconic concert film Yura Yura Teikoku 2009.04.26 LIVE @ Hibiya Open-Air Concert Hall, Ōne made a powerful entrance into feature films with his debut Moteki in 2011. Since then, he has crafted compelling stories both behind the camera and on the page with works such as Bakuman., SCOOP!, and Sunny: Tsuyoi Kimochi Tsuyoi Ai. In recent years, his creative reach has expanded to directing the intense drama Elpis — Hope or Disaster and helming the Netflix series Tokyo Swindlers, showcasing his talent for blending emotional depth with striking visuals.

This was just before the pandemic hit. Since Ōne and I are the same age and had spent time in similar circles when we were younger, he had taken an interest in my book. Because I was friends with Kuroki, the Fuji TV producer, it naturally led to us meeting.

Ōne: During that dinner, Matsunaga told me about New Hakuba, a grand cabaret with a unique atmosphere in his hometown of Yatsushiro City, the last of its kind in Japan. Matsunaga said, “I’ve always dreamed of seeing Shintaro Sakamoto perform there.” I didn’t know about New Hakuba before, so I looked it up right away and was impressed. That night, we got excited and said, “If this actually happens, it would be incredible.” That was how it all started.

But it wasn’t immediate. In 2022, when the “Like A Fable” tour schedule was announced and New Hakuba was included, I thought, “That’s it!” At first, I just planned to go watch the show like any other fan.

Just as an audience?

Ōne: Yes, that’s right. But then, suddenly, I thought, “I want to film that live show…” Since Shintaro Sakamoto released four solo albums and started live performances in 2017, I had been watching him all along. If I may say so, I felt the band had really come together. The variety of songs, the musicianship, the performance, and the energy from the audience — everything had grown stronger. I thought, “I want to film this current Sakamoto band! This concert absolutely must be preserved on film!” It felt almost like a calling.

I get that. And the setting was perfect too.

Ōne: But I knew from Sakamoto’s Yura Yura Teikoku days that he wasn’t really interested in recording live performances. Still, this time I really wanted to film it. The feeling that this should be preserved as a cultural treasure kept growing inside me. One night, I decided to ask Sakamoto directly. I emailed him saying, “Hakuba is amazing. I want to film the live show there.”

How did he respond?

Ōne: As expected, he said he wasn’t really interested [laughs]. But after a few exchanges, I proposed, “Then I’ll film it independently as a personal project. Would you allow that?” And he said, “If you’re filming it on your own, that’s fine.” So, I was granted permission strictly as an independent project inspired by my own passion.

Around that time, I was shooting the TV drama Elpis — Hope or Disaster (2022). The cinematographer on that project was Yutaro Shigemori, who isn’t just a drama cameraman but also worked on music videos for Cornelius. Shigemori is a big fan of Sakamoto’s music. When I told him on set, “I’m going to film Sakamoto’s live show,” he said, “I want to shoot it.”

It feels almost fated that you were directing Elpis at the same time. That drama’s visuals were incredible.

Ōne: When we looked at photos of the inside of New Hakuba, Shigemori said, “If we’re going to film Sakamoto here, wouldn’t 16mm film be a perfect fit?” That idea never occurred to me. Shigemori mainly shoots on film rather than digital. The look of 16mm film is unique — it’s not as sharp or detailed as 35mm film, but it has a special charm and texture. I thought, yeah, that might actually work. But filming on actual film costs money. Luckily, Kodak and Imagica had a program to support 16mm film productions to keep the format alive, covering costs like film stock and development if the project qualified as a movie or video work. Shigemori reached out to them, and in the end, they agreed to support us. That was when things really started moving forward.

INDEX

The Struggles Behind the 16mm Shoot With Just 2 Cameras in Action

That said, there must have still been a lot of challenges to overcome, right?

Ōne: Absolutely. 16mm film cameras just aren’t used much on sets anymore. Even if we could gather the cameras and operators, we also needed skilled assistants to handle the film changes.

I didn’t realize it myself until I saw it firsthand, but each camera needs a three-person team. It reminded me of Bunraku puppeteers—three people all working in sync around one camera.

Ōne: That’s right. Each roll only gives you about 11 minutes of footage, and when it runs out, you have to swap it immediately. But you can’t just switch it out casually—you have to cover it with a black cloth to avoid exposure, and loading the film into the magazine is practically a craft in itself. We had to bring in assistants who were trained in that kind of precision work. On top of that, we had to coordinate with a crew for cranes and dolly tracks—specialized equipment. In total, we had a 30-person team.

We also hunted down six operational 16mm cameras from all across Tokyo. After doing a thorough location scout, we were finally ready for the big day: December 5.

Was there anything you realized only after actually visiting New Hakuba?

Ōne: The stage was a bit darker than I expected—well, it is a cabaret after all. But with film, you need a certain level of light to shoot properly. So for the actual show, I brought along Hikaru Chikamatsu, who had worked as an assistant chief lighting technician on Elpis, to help add some side lighting. More than anything though, just seeing the space with my own eyes, I thought this place is seriously incredible. The idea of Shintaro Sakamoto performing here just got me even more excited.

During the show, you were up on the second floor, right?

Ōne: Yeah. I think it used to be part of the seating area, but it had been converted into something like a control room. That’s where I set up base, watching the monitors and giving directions to the camera operators via intercom. It’s the standard way to shoot live concerts. But with digital, the monitors give you a clean, high-res image. With 16mm, we had to use these old-school monitors called “bizicons,” and the footage looked like some grainy bootleg from the Showa era—just awful quality [laughs]. So the whole time I was watching these rough images during the performance, I couldn’t help but worry a little, “Are we really getting the shots we need?”

Were you also keeping track of the timing for film changes for each camera?

Ōne: I had all of Sakamoto’s songs memorized, so I could generally direct the flow and camera work for each track. Of course, if we’d rolled all the cameras at once from “Ready, action!” we’d end up with periods where none were running. So we staggered the start times intentionally.

There were actually moments in the middle where only two cameras were rolling. In those cases, I’d get on the intercom and tell the operators, “Only two cameras are on right now—do not miss this shot!” It added this extra layer of tension and thrill to the shoot.

These days, concert films tend to be packed with dozens of cameras and rapid-fire cuts. But at New Hakuba, you were working with just six cameras, and on top of that, having to stop every 11 minutes for film changes. So there are a lot of long takes in the final cut.

Ōne: Exactly. I think the limitations in equipment and setting actually worked in our favor. As I mentioned, we added just a touch of lighting, but it was barely noticeable to the audience. For the most part, we relied entirely on the lighting that was already installed at the cabaret.

Even the lighting operator we brought in was someone local who usually handles regional events. The control board didn’t even have faders, just these chunky on/off switches you slam down. When you hit one, it would change the background color or make the decorative light columns on both sides start spinning.

And those spinning columns were definitely a highlight! [laughs]

Ōne: They were incredible—and had this wonderfully improvised, handmade charm to them. [laughs] Of course, we had professionals working on the shoot, but the atmosphere was almost the opposite of polished. It felt like a true passion project, with all the energy of a DIY production.

Also, compared to Tokyo audiences, who tend to be intensely focused, like “Okay, I’m here to watch this seriously.” The crowd at New Hakuba was much more laid-back. People were chatting during the songs, heading to the bar mid-set to grab drinks… It was still during the later phase of the pandemic, but there was this loose, easygoing energy that just felt right. The band picked up on it too—you could feel the exchange between them and the audience. As we kept filming, I could tell we were capturing something real and vibrant. Even if the monitor image was grainy beyond belief. [laughs]

INDEX

Differences Between Yura Yura Teikoku and Sakamoto’s Solo Work from Ōne’s Perspective

Looking back, you captured Yura Yura Teikoku’s final live performance at Hibiya Open-Air Concert Hall on April 26, 2009, which was released as the film ”Yura Yura Teikoku 2009.04.26 LIVE @ Hibiya Open-Air Concert Hall,” correct?

Ōne: I discovered Yura Yura Teikoku after their major debut, but when their albums ”Yura Yura Teikoku no Shibire” and ”Yura Yura Teikoku no Memai” (both released in 2003) came out, I truly realized, “Wow, something extraordinary is happening here!” I attended nearly all their live shows in and around Tokyo. Being able to film their final show at Hibiya was a perfect convergence of my passion as a fan and my profession as a director. In my view, Yura Yura’s later work represented the pinnacle of Japanese rock music that I had experienced.

Did you feel a connection between filming the Hibiya Open-Air live and the recent show at New Hakuba?

Ōne: Absolutely, I see those two projects as completely connected. The Hibiya live wasn’t an independent production either, but the budget was pretty limited back then as well [laughs]. How I got involved was pretty spontaneous — about two or three months before the show, I happened to meet Akimasa Yabushita, who was Yura Yura Teikoku’s A&R at the time, while having drinks in Shimokitazawa. They hadn’t chosen a director yet for the filming, so I just volunteered on the spot, saying, “I’m the right person for this!” and that was how it got decided [laughs]. At the time, the plan was only to air a one-hour highlights program on Space Shower TV.

So, it wasn’t originally meant to be released?

Ōne: Exactly. But then, Yura Yura Teikoku disbanded the following year. We shot the Hibiya live with digital cameras, but since the lighting was really dim, we had to push the exposure way up. This made the footage grainy, giving it a look that, while digital, felt like old film.

That was the only full live recording of Yura Yura Teikoku I ever did. Maybe Sakamoto saw that and thought this kind of footage was worth keeping. I also believe that Sakamoto’s reluctance toward live videos comes from thinking the bright, crisp quality of modern digital doesn’t really match their live vibe.

I really understand that feeling.

Ōne: While my main work has been shooting films and dramas, and I have affection for all of them, if asked about my personal best, I would say it’s Yura Yura Teikoku 2009.04.26 LIVE @ Hibiya Open-Air Concert Hall. To me, it’s a perfect work. Especially the filming and editing of the song “Nai!!” is something I believe I could never recreate again, it’s the ultimate form. I thought I would never surpass that, but with the recent live footage at Cabaret New Hakuba, I feel like I either surpassed it or at least matched it. I think my best work has been updated.

By the way, from your perspective, what are the differences between Yura Yura Teikoku and Shintaro Sakamoto’s solo live performances?

Ōne: I think they are completely different. Not in a negative way, but simply the volume became smaller after going solo. The later Yura Yura Teikoku shows had a unique tension between the stage and the audience. There was excitement, but the crowd wasn’t just “woo!” — it was more intense, a sharp atmosphere. Especially after the release of Kūdō desu (2007), the audience seemed like they were on guard, as if thinking, “What’s next? What will happen? What kind of arrangement will come? I’m not going to miss a single moment!” I felt that tension myself too [laughs].

Ōne: Since Sakamoto went solo, the live shows seem to have a looser connection between the stage and the audience. I recall reading an interview where he mentioned that it’s okay if people chat quietly in the back during the performance, and that he wants the band to feel more like a casual backing group. Also, the music has grown into a mature, adult form of rock that suits his age.

Are there any aspects that remain consistent between the two?

Ōne: While I always saw Yura Yura Teikoku in their later years as the ultimate rock band, Sakamoto’s solo project has developed into something truly one-of-a-kind. You won’t find another band like it anywhere in the world. Being able to witness the Shintaro Sakamoto Band in this era is a real privilege, and I feel incredibly fortunate.

INDEX

Preserving Shintaro Sakamoto’s Live Performance as Cultural Heritage

In 2023, the New Hakuba footage was exclusively screened at LIQUIDROOM (May 17, 2023, with two showings). What made it special was the use of three screens arranged side by side!

Ōne: After finishing the shoot, I kept wondering how best to present the work. When I developed some film cuts, they looked fantastic. I showed them to Sakamoto-san, and he responded positively—I half-joked that he probably thought, “Film me looks cool” [laughs].

Since the Yura Yura Teikoku footage from the Hibiya Open-Air Concert became a staple screening at the “Bakuon Film Festival,” an event dedicated to showcasing powerful live music films with immersive sound, I wanted to create a similar experience for the New Hakuba footage. My idea was to hold a screening at a live house like LIQUIDROOM, where the audience could watch standing, feeling the energy of a live show. I pitched this concept to Sakamoto-san. Originally, I planned to use just one screen, but during editing, I realized the film material was so rich and vivid that it deserved more than a single screen. That’s when the idea of using three screens came about.

You even had new screens made specifically for this, right?

Ōne: Yes, I spoke with LIQUIDROOM about placing three screens on stage in a wide “V” shape and paid out of pocket to have them made.

Filming in Hakuba was already expensive, and then you invested even more! [laughs]

Ōne: Yeah, I guess I was a bit crazy [laughs]. But more than anything, I just really wanted to see it myself. For the first screening, the audio wasn’t just pre-recorded from the footage, Sasaki Yukio, the sound engineer who works on Sakamoto-san’s live shows, mixed the sound live on site. It created an experience like watching a live concert on the three screens. There were some minor hiccups during that first screening, though.

During the screening, the video malfunctioned and stopped midway. At that moment, you grabbed the microphone to apologize and explain the situation. When the video started again, the audience went absolutely wild. It really felt like a live concert where something went wrong but then had a miraculous comeback.

Ōne: That’s exactly how it was.

For the re-screening at LIQUIDROOM on April 13, 2024, there was an all-night double feature including a live show at Hitomi Memorial Hall (October 26, 2022) filmed by Yasuyuki Yamaguchi. Just a few days prior, news came of Chiyo Kamekawa’s (ex-Yura Yura Teikoku) passing. At the very end, you took the mic again and as an encore screened the Yura Yura Teikoku live at Hibiya Open-Air Concert Hall. It was a powerful moment, full of meaning and connection.

Ōne: It was deep into the night, just two songs played: “Imadani Mahou ga Tokenumama” and “Nai!!”

That entire arrangement was only possible because of you. No one else could have pulled it off.

Ōne: Probably true. I contacted Sakamoto just a couple of days before and asked if we could include those two songs at the end. We had amazing footage of Kamekawa in those performances. Everyone who stayed until dawn watching must really have loved Yura Yura and Sakamoto. It felt like we were all able to say a proper goodbye together.

And about a year after that screening, it was released on Netflix.

Ōne: Just as my documentary film Tokyo Swindlers began streaming on Netflix, I was offered an exclusive contract. While discussing what to do next, I said, “Actually, I have this project, how about this?” and proposed the New Hakuba live footage. There were fans of Sakamoto-san within Netflix, and they said they definitely wanted to stream it.

Looking back, it’s really moving that this project, starting from when you first learned about New Hakuba in 2020, has taken five years to come this far.

Ōne: When I think about it, it all began with a single comment from Matsunaga-san. I feel like I fulfilled his dream—or maybe I was just being played in his hands [laughs]. But above all, that live show was a one-night-only miracle, and being able to preserve it is a true honor as a director. I want to say to myself, “Well done, you made the decision!”

It reminds me of T.A.M.I. Show—the 1964 concert in California—where future generations look back and are grateful that someone captured the energetic James Brown and The Rolling Stones. It’s like a cultural heritage or a personal patronage, a desire to create something that will still be seen 100 years from now and preserved properly.

INDEX

Sakamoto’s Hidden Side Seen Through Ōne’s Eyes

Between “Yura Yura Teikoku 2009.04.26 LIVE @ Hibiya Open-Air Concert Hall” and “Shintaro Sakamoto LIVE 2022 @ Cabaret New Hakuba,” there was the drama directed by Ōne, Tada’s Do-It-All House (2013). Sakamoto, now solo, provided the background music for the show as well as the ending theme, “Don’t Know What’s Normal.”

Ōne: Ever since I started working on dramas, I’ve taken care of commissioning the background music myself. Whether it’s for dramas or films, I don’t often go with professional composers. Instead, I like to collaborate with musicians, DJs, and track makers whose music I really connect with, because I want the soundtrack to reflect the music I genuinely love.

I reached out to Sakamoto after hearing the instrumental versions of all the tracks included in the first pressing of his solo album, How To Live With A Phantom (2011). That’s when I thought, “Wow, Sakamoto could definitely handle scoring background music.” People often see Sakamoto as somewhat mysterious or veiled—not quite a deity, but someone with an enigmatic presence. Yet in everyday life, he’s easy to talk to and quite sociable. Of course, he wouldn’t accept any work he wasn’t fully satisfied with, but for Tada’s Do-It-All House, he read the script, felt comfortable with it, and tackled the project with a craftsman’s dedication. The score he delivered perfectly matched the world of the drama and exceeded my expectations.

The song “Don’t Know What’s Normal” was born from the content of the drama, wasn’t it?

Ōne: The opening song was already decided to be “Beautiful Dreamer” by Flower Companies, so I wanted to ask Sakamoto-san to create the ending theme. I requested a song that would leave a lingering feeling from the drama—something warm yet bittersweet. I still vividly remember when the demo arrived. It came when about half of the shooting was done, with a message saying, “I’ve made something good.” I thought, “Sakamoto-san actually said, ‘I’ve made something good’!” [laughs] When I listened to it right then and there, from the intro to the final fade-out, everything was perfect, and I got goosebumps the whole time. I don’t think anything will ever top it in my lifetime.

Fans can also catch an amazing performance of “Don’t Know What’s Normal” in “Sakamoto Shintaro LIVE 2022 @ Cabaret New Hakuba.”

Ōne: Come to think of it, the setlist for the October show at Hitomi Memorial Hall, which happened just before New Hakuba, didn’t include “Don’t Know What’s Normal.” But it was definitely part of the New Hakuba set. Sakamoto-san never openly says, “I included that.” Later, I asked him, “Did you put it in because I was filming?” His reply was, “Well… I guess that’s part of it” [laughs]. That’s just the kind of person Sakamoto Shintaro is.

Sakamoto Shintaro LIVE 2022 @ Cabaret New Hakuba.

Performers: Shintaro Sakamoto, AYA, Yuta Suganuma, Toru Nishiuchi

Director: Jin Ōne

Streaming starts on Thursday, May 1, 2025, on Netflix.

*Available for a limited time only.