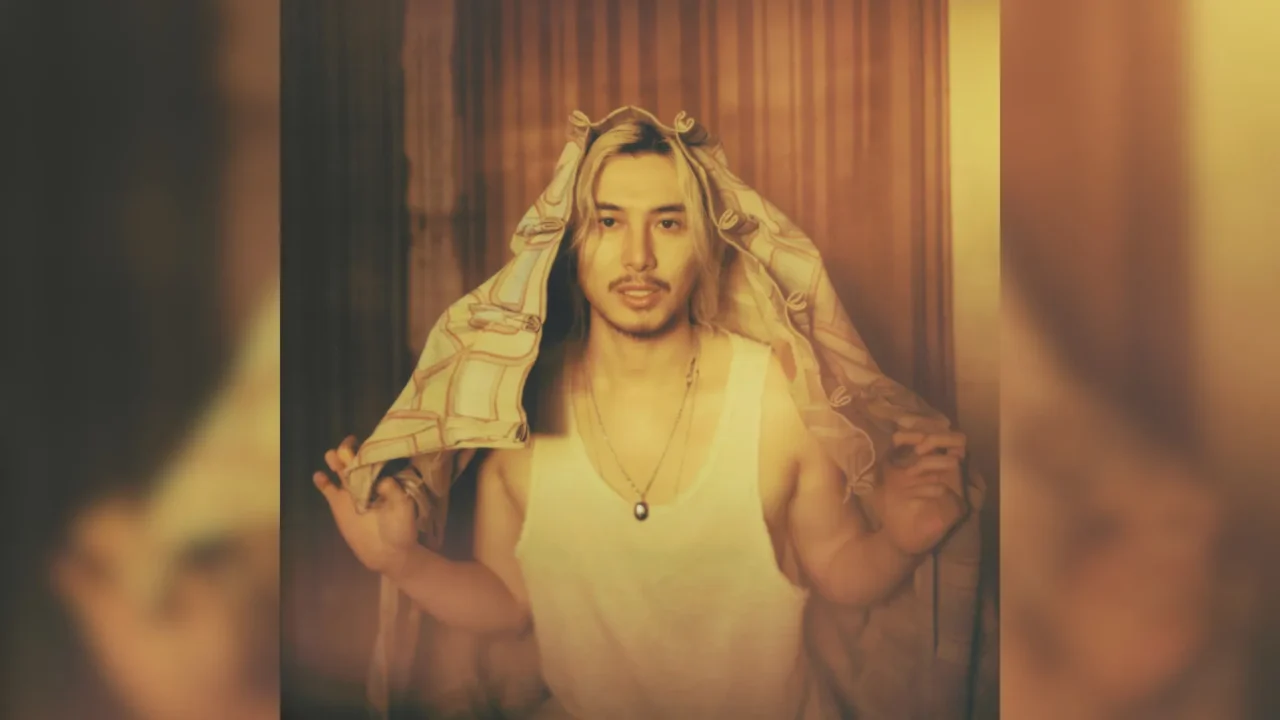

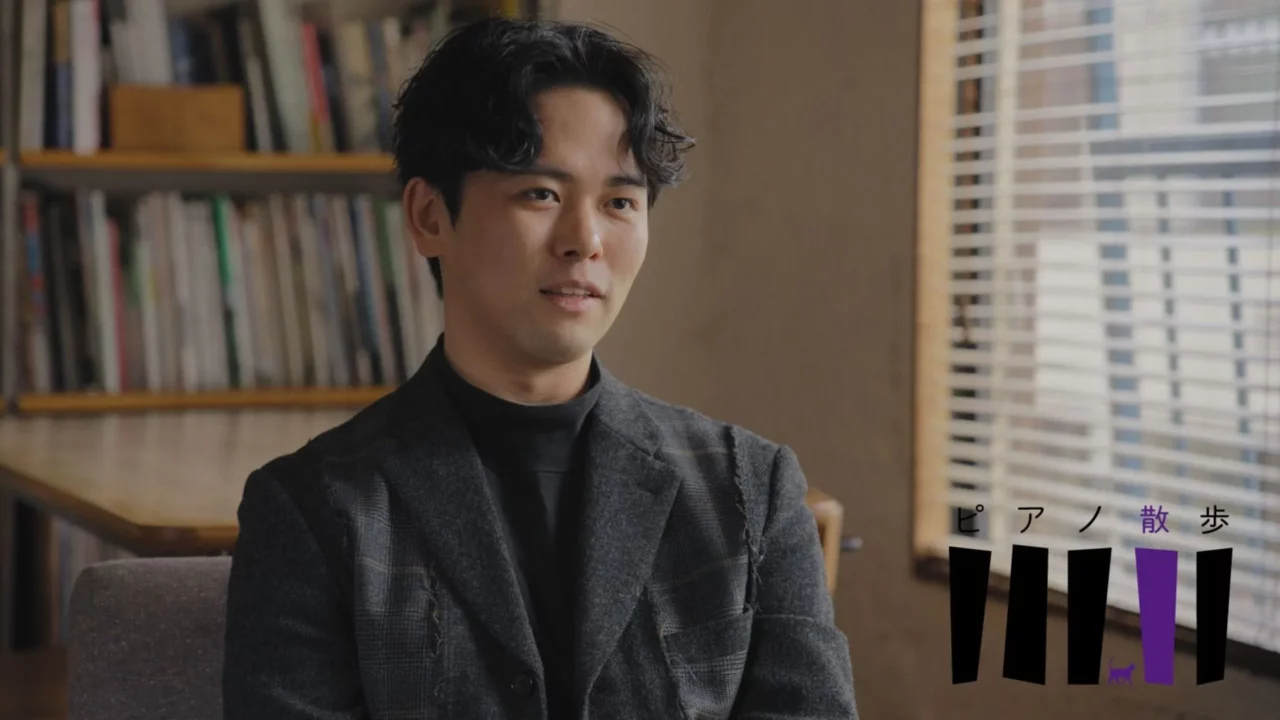

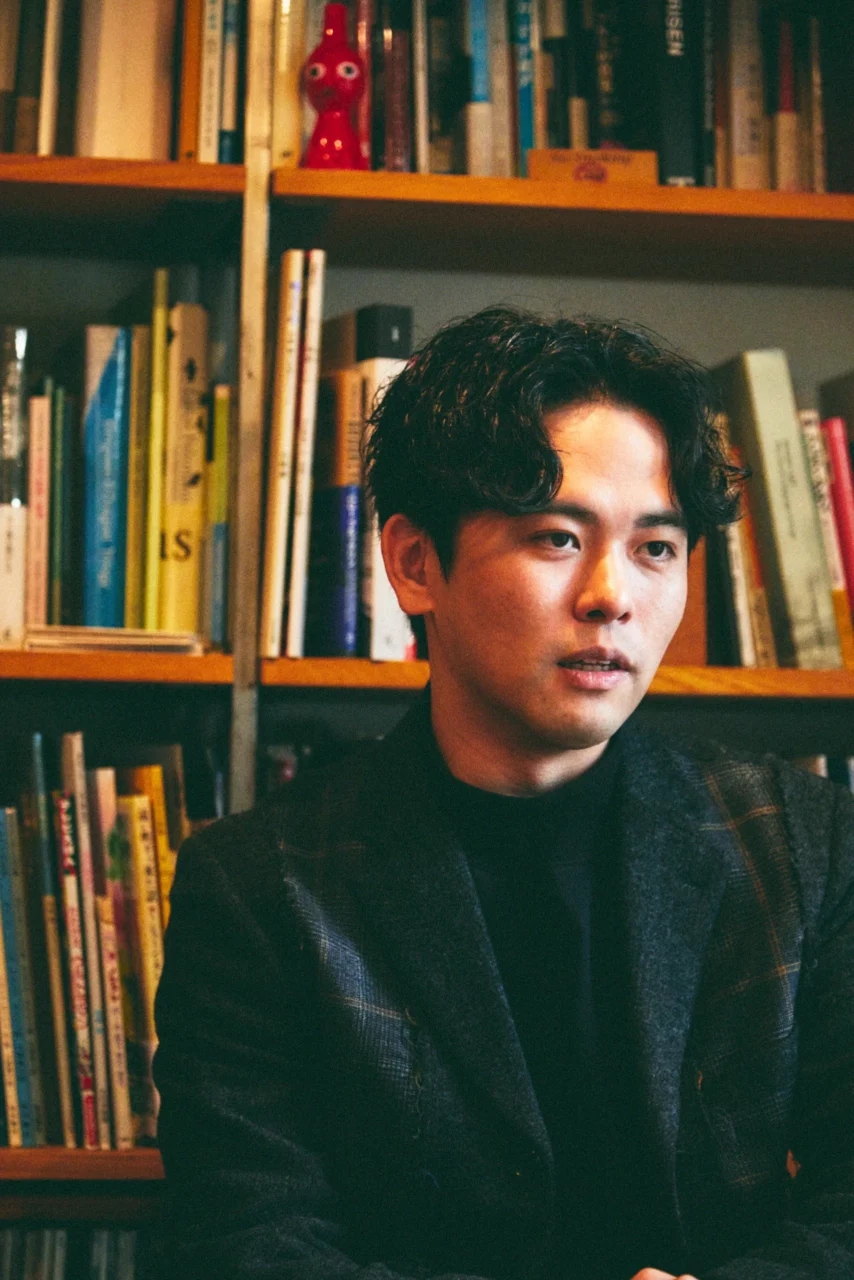

Ayatake Ezaki, the keyboardist of WONK, has always pushed the boundaries of music, blending genres and exploring new soundscapes. Following the release of his debut solo album Hajimari no Yoru in May 2023, he’s gearing up to share Shades of—WONK’s first album in two and a half years—this November. A musical tapestry that blends digital and analog elements, improvisation and structure, Shades of is a culmination of Ezaki’s evolving vision and his deep connection with the keyboard.

But Ezaki’s journey doesn’t end with his band or solo work. His unique style has also found a home in the world of film music. In this interview, he reflects on his longstanding relationship with the piano, starting from his childhood, and opens up about how he went from resisting practice to forging a distinctive musical path all his own.

Yamaha Music Japan’s subscription service designed to support musical instrument performance. Click here for more details.

INDEX

The New Album by WONK: A Blend of Everything They’ve Created So Far

In November 2024, WONK’s new album Shades of was released with the tagline “A Beat Music Chronicle from Tokyo.” Mr. Ezaki, what kind of expression were you aiming for with this album?

Ezaki: Actually, this tagline came up during a meeting with the staff after all the tracks for the album were completed. In other words, we didn’t set this theme from the start. However, when I listened to the finished product, I really felt that over the past ten years, we’ve created a wide variety of music. Some bands might decide on “this is our style” and stick to that direction consistently, but we’ve always been open to eagerly absorbing whatever we found interesting at the time.

Musician. Born in Fukuoka City in 1992. He began learning piano at the age of 4 and started composing at 7. He graduated from the Faculty of Music at the Tokyo University of the Arts and completed his master’s degree at the University of Tokyo. In addition to being a keyboardist for WONK and millennium parade, he has contributed to numerous artists’ works, including King Gnu, Vaundy, and Kenshi Yonezu, through recording and production. He has also composed film scores, including for Homunculus (2021), and is involved in managing a music label and participating in arts education. Ezaki continues to freely cross various fields in his artistic pursuits.

The 4th album EYES, released in 2020, was a grand concept album that depicted diverse values in the information society through a sci-fi story. The following album, artless (2022), captured the subtle nuances of the heart and everyday scenes. How would you describe your latest work after these two?

Ezaki: I feel that it’s “a mix of all the elements we’ve used so far.” I can appreciate the digital aspects, like in EYES, and also the analog expressions, like in artless. Instead of choosing one over the other, I think the key feature of this new album is that we’ve placed both elements side by side without hesitation.

I also felt that in this work, your piano plays a more significant role than ever before.

Ezaki: I didn’t particularly intend for that to happen. However, our leader, Arata (Kou) on drums, would say things like, “We have this kind of song, but I’m not playing drums on it.” He’s such a kind leader, so perhaps he wanted to respect and incorporate the musical direction I was exploring solo. In fact, I think there were quite a few tracks, especially in the first half, that were built around the piano.

INDEX

Focusing on Achieving a “Good Sound” on the Piano

In a previous interview, you mentioned, “When we made our first album, ‘Sphere,’ I couldn’t even think about things like which mic to use. But over time, working with everyone, I’ve been able to expand what I can do, and I feel like I can now draw out various colors from keyboard instruments.” Do you feel that you were able to materialize the sound you wanted with more clarity this time?

Ezaki: Absolutely. When we first formed WONK, I hadn’t really thought deeply about the sound of the piano. As a jazz pianist, I was in an environment where playing the piano as it is was the norm, so I didn’t have the awareness of “shaping my own sound.” But as I gained more recording experience, the image of “what kind of instrument I want to play” and “what kind of sound I want to create” became clearer and clearer.

For Shades of, I used a variety of pianos—upright, grand, and even electronic sounds—while carefully considering the intent behind each sound. I also had the piano at STUDIO Dede, which I’ve always used, re-felted to my specifications (laughs). In the past, I thought just tuning it properly was enough, but I realized that small details, like noise textures, can sometimes lead to a “better sound.” My approach to the piano and my awareness of it have completely changed from before.

Are there any influences from artists like Nils Frahm and Ólafur Arnalds, who were mentioned in today’s Yamaha Music Members Plus video, on the acoustical aspects of the piano sound and performance beyond just the playing itself?

Ezaki: They are both performers and composers, but what inspires me the most is their approach not just as players, but as sound designers who carefully craft the acoustics as part of the recording art. Come to think of it, the organizer of THE PIANO ERA 2024, which I recently participated in, mentioned, “I always gather eccentric pianists.” Almost all the artists who performed there were not only players but also sound designers. Some even brought metal plate microphones from Europe and experimented by placing them inside the piano during tuning to record the internal sounds.

In Japanese concert halls, there’s a strong focus on having a designated tuner bring the piano to its best state, which makes it difficult to approach sound acoustically. The notion that a piano must be played “beautifully and correctly” is still quite prevalent, but I believe that if there’s more room for free thinking, it could open up even more possibilities for expression.

Did your increased awareness of tone and sound production come primarily from your solo activities?

Ezaki: Actually, it was more influenced by the bands and the J-pop artists I’ve worked with as a guest performer. Being inspired by them, I started to think more deeply about the sound of the piano, which eventually led me to the desire to try doing something solo. So, if I had been working solo from the start, I might still just be a player focused solely on the keyboard.

INDEX

Creating Works Based on Shared Emotional Experiences

It’s a big advantage that WONK has bassist Inoue, who also has engineering skills, right?

Ezaki: I think it’s a huge strength. Inoue is also active in the gaming world, so he has knowledge of surround sound, for example. He brings that into his sound production ideas, which is something that’s hard to come by in a regular band. In fact, we had the goal of finishing this album in Dolby Atmos. I feel his presence will become even more important in the future.

I recently attended WONK’s tour, and the Tokyo performance featured a unique setup with a center-stage arrangement. It felt like listening to music in surround sound, didn’t it?

Ezaki: Exactly. I’ve been really enjoying live performances lately, but the center-stage setup felt especially fresh. Just changing the position you stand in really alters your perception, and I realized it has a big impact on the performance.

What kind of impact does that have?

Ezaki: Normally, on a regular stage, you’re more conscious of being watched, but when surrounded like that, it feels more like creating music together with the audience. It’s like boxing or sumo, where the audience is all around you during the match. I think it was a similar feeling. The energy coming from all directions was incredible.

Facing each other and playing together, like forming a circle, must have affected the performance too, right?

Ezaki: It was certainly fresh to see vocalist Nagatsuka (Kento) facing us, haha. He’s not a musician, so he hasn’t really taken a leadership role in our band performances until now. But this time, with everyone facing inwards, Nagatsuka led a part where he added beatbox elements and guided the ensemble. I think he also felt the joy of “leading the music,” and we felt like we were being pulled along by him, which felt really good. As a result, I think it positively influenced the whole band.

The solo battle between you and Arata was absolutely captivating.

Ezaki: Thank you [laughs]. It really took me back to my jazz club days. It felt like we were breaking all the rules we were supposed to follow. Honestly, I think I’d forgotten just how much fun it was to do that over the years.

The turning point was when we played a live show in Nagatsuka’s hometown of Akiruno last fall. For the first time in a while, we all played live instruments, and there was this sense of freedom, like, “Why do we even need a setlist?” (laughs). We just played what came to us, singing along and letting the performance flow naturally. Of course, we still had a setlist, but during the show, we intentionally broke things apart, and somehow everyone was able to keep up and transition into the next song smoothly. The spontaneous call-and-response was a blast, and I think that vibe from that show has carried over into our current tour.

After wrapping up the tour, how do you feel about WONK’s identity and direction at this stage?

Ezaki: Honestly, I don’t have a clear vision yet [laughs]. With this album, I feel like we’ve poured everything we’ve done up until now into it. So, if we keep producing at this pace, I think we’ll just end up repeating ourselves. Right now, I think it’s time to take a step back and focus on gathering new ideas for the next phase.

Ezaki: WONK is a band that has always valued those kinds of moments. Even before releasing our first album in 2016, we spent three years without releasing much, just focusing on making music, eating meals together, and going to concerts as a group. After spending that time together, we create music based on the emotional experiences we each brought to the table. For us, that feels like the most natural way to approach things.

INDEX

Drawn to Music Outside Rigid Boundaries

In the recently released video for Yamaha Music Members Plus, we discussed your early encounters with the piano and the reason you started playing. I was particularly surprised to hear that you played blues at your recital, and I thought that might have been the starting point for your love of Bill Evans. Why do you think you were drawn to the muddy sounds and the different resonance, which were unlike classical music?

Ezaki: Hmm, honestly, I’m not entirely sure why, but I’ve always struggled with structured music like Bach, Mozart, or Beethoven. Music that is built on a solid framework never quite sat well with me. Of course, Mozart has parts that break away from that, but Bach and Beethoven’s music has such a beautiful structure, you know? I just didn’t enjoy confronting that type of music.

Maybe my piano teacher at the time sensed that I wasn’t a fan of it. It wasn’t just blues; I also got to play a Latin piece called “Brazil.” But back then, I wasn’t even aware of whether it was blues or Latin music. In any case, I think I was naturally drawn to music that doesn’t fit neatly within structured boundaries.

But that teacher was amazing. They didn’t force anything on you.

Ezaki: xactly. What’s more, I was the first student on Saturday, so the teacher would say, “Come a little earlier,” and extend the lesson by 30 minutes. During those 30 minutes, I could play whatever I liked, like Latin music or blues. But, in exchange, the remaining regular lesson time was strictly focused on the curriculum and the basics. It was really an environment where I could freely enjoy music.

Unfortunately, the teacher’s lessons ended because they moved. The next teacher I had was extremely strict (laughs). They asked, “What have you been doing until now, in 3rd grade?” and drilled me hard on the basics.

[laughs]

Ezaki: The time to learn basic techniques inevitably comes at some point, but I’m glad it didn’t come first for me. I think it’s because I was able to freely approach music at the beginning that I was able to continue playing. Since I was little, my parents always had music playing at home, and they actively took me to concerts, so the atmosphere at home was really great. That said, practice was still really tough (laughs). If I hadn’t discovered jazz when I was in middle school, I might not have continued with the piano.

But now, I think it’s good that I learned to read and write music as part of the basics. In the end, both are necessary. Motivation to enjoy playing is, of course, important, but if you’re collaborating with others, you need a way to communicate. Writing music becomes a common language to convey your ideas.