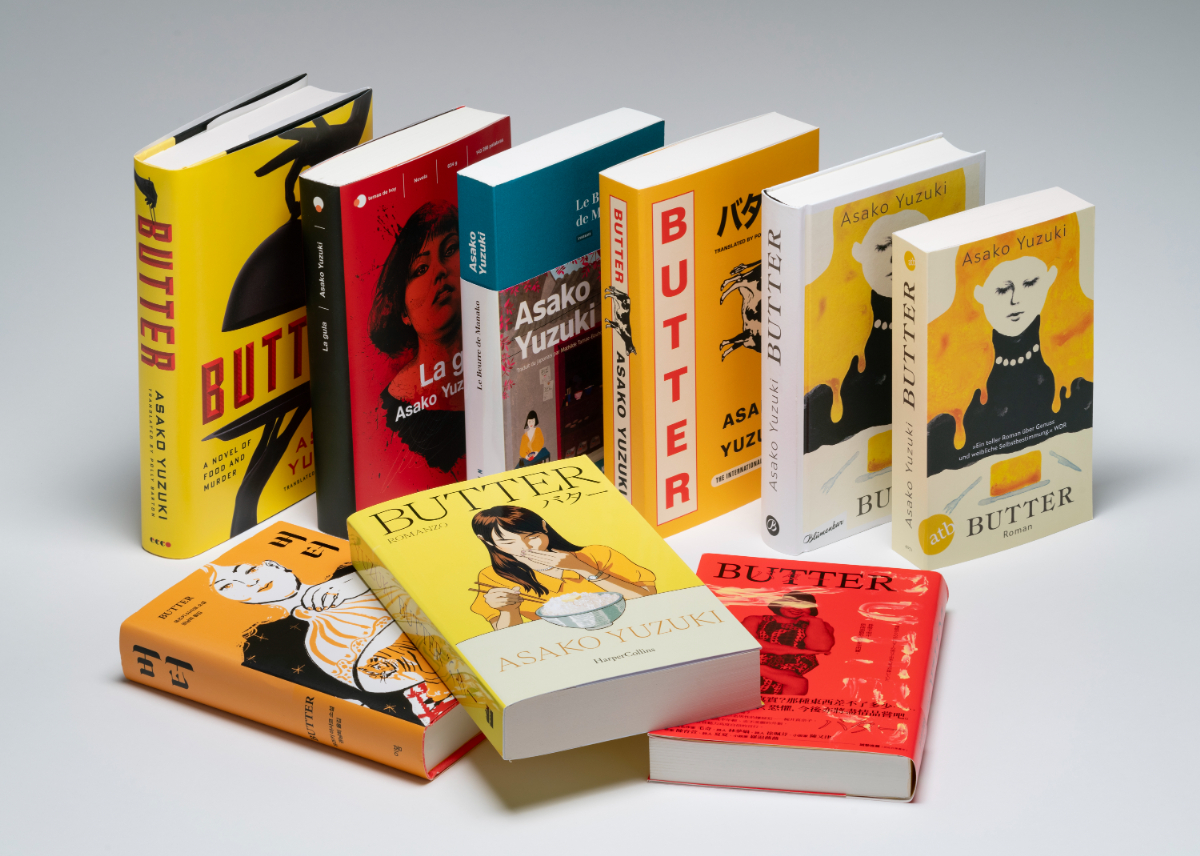

Asako Yuzuki’s novel BUTTER, which is being translated into 35 languages worldwide, had its English edition released in 2024. It became a bestseller, with over 260,000 copies sold in the UK and over 100,000 copies in the US. It also made history as the first work by a Japanese author to win the Waterstones Book of the Year 2024, awarded by a major British bookstore chain.

According to Yuzuki, Japanese literature is currently experiencing a boom outside of Japan. This growing popularity led to her being invited on an authors’ tour across six cities in the UK, where she also gave a lecture at Oxford University. She has also visited countries such as India and Hong Kong. Reflecting on the time when her novel was criticized by male intellectuals in Japan, she never imagined it would eventually be endorsed by artists like Dua Lipa upon its release. Eight years after its publication in Japan, as she continues to travel the world with BUTTER, NiEW delved into the theme of “unease in living” in her book and explored her insights on finding the right balance of comfort in life.

INDEX

Never Imagined Such Popularity in Her Lifetime: A Parallel World of Global Reception

BUTTER was first published in 2017, at a time when, as Professor Toko Tanaka from the University of Tokyo pointed out, public opinion on feminism began to shift noticeably. I remember reading BUTTER back then and how it became a pivotal book that opened my eyes to different perspectives on feminism.

Yuzuki: Thank you very much.

After the paperback edition was released in 2020, BUTTER was translated into 35 languages, including English, French, and Italian. As you’ve traveled to different countries for lectures and events, did you feel the overwhelming international response firsthand?

Yuzuki: To be honest, I never imagined that my book would become this popular in Japan. It felt almost like entering a parallel world.

When I visited India, there were so many people asking for photos, and the line for autographs seemed endless. I signed so many books that my hand started to hurt.

What left the biggest impression on you?

Yuzuki: There are many things, but one thing that really surprised me was the large number of male fans. In Japan, BUTTER might be seen as literature aimed at women, but in English-speaking countries, it’s being interpreted as a form of “moderate” feminist literature that also addresses the struggles men face.

That said, the book’s success isn’t just due to my efforts alone. The ongoing boom of Japanese literature in the UK and the amazing work of Polly Barton, who translated the book, were key factors as well.

Photo © Shinchosha

Born in Tokyo, Asako Yuzuki made her literary debut in 2008 with Forget Me, Not Blue, which earned her the esteemed All Yomimono Newcomer Award. Her debut collection, Shūten no Ano Ko, which features Forget Me, Not Blue, launched her distinguished writing career. In 2015, she was awarded the Yamamoto Shūgoro Prize for Nile Perch Girls’ Club. Renowned for her thought-provoking and captivating storytelling, Yuzuki’s acclaimed works also include The Hotel of My Dream, Akko-chan’s Lunch, Ito-kun A to E, and All Not.

Polly Barton is a renowned translator of Japanese literature, earning significant acclaim for her work. She received the PEN Translation Prize for her English rendition of Kikuo Tsumura’s There’s No Such Thing As An Easy Job and the World Fantasy Award for her translation of Aoko Matsuda’s Where The Wild Ladies Are, solidifying her reputation in the literary world.

Yuzuki: Similar to how readers in Japan are eager to explore books translated by Sachiko Kishimoto or Mariko Saito, Polly Barton has become a charismatic figure in the English-speaking world. During my overseas lectures, the most frequent question I was asked was, “Have you met Polly?” It seems that many readers trust her translations, believing that if Polly Barton is behind a book, it’s bound to be excellent.

INDEX

Literary Works Born from Japan’s Distinctive Culture

There’s been a lot of talk about the Japanese literature boom, with works by authors across different generations, from younger writers like Sayaka Murata and Aoko Matsuda to established names like Yoko Ogawa and Mieko Kanai, being embraced overseas.

Yuzuki: That’s what I find so interesting. It’s not only the internationally acclaimed authors from an older generation, like Yoko Tawada or Yoko Ogawa—there’s a growing sense that reading books by Japanese women writers in their 40s is now seen as chic and culturally savvy.

Like, “Oh, you know about that?”

Yuzuki: I think it all started with Sayaka Murata. Her novel Convenience Store Woman gave readers this eye-opening look at how many different tasks are involved in working at a Japanese convenience store. That sense of novelty really struck a chord. With BUTTER, I think the most surprising detail for readers was the idea that there are virtually no women in senior editorial roles at weekly magazines. I based that on actual interviews with people in publishing, but I kept getting asked, “Wait, is that really the case?”

So from an international perspective, Japan can come across as quite unusual?

Yuzuki: I think Japan really does have a unique culture. For instance, Seichō Matsumoto’s mystery novel Points and Lines is currently popular in the UK, but there are parts of it that British readers find hard to wrap their heads around. The story involves a crime that takes place on a train platform, and the key trick hinges on the train arriving exactly on time. But to people in the UK, that kind of punctuality feels miraculous—they’ll say things like, “Was this murder just a gamble based on coincidence?” And I’m like, no, no, no—not at all!

So it’s a meticulously calculated murder, all based on train timetables. [laughs]

Yuzuki: Exactly—it’s painstakingly planned! People say, “But a train arriving exactly on time? That’s impossible!” And I tell them, in Japan, if a train is even one minute late, there’s an official apology announcement. That just blows everyone’s mind. With Convenience Store Woman, too, there’s this sense of learning about Japanese culture through fiction. I’ve even heard that some people traveled to Japan just to see if what’s written in the book is really true. I think that’s why Japanese literature feels so close and accessible to readers abroad.

Are there more people reading books in other countries?

Yuzuki: Yes, there are definitely more people reading, and those who do, read quite a lot. When I was in Germany, I particularly noticed that, despite the clear income disparity, people are paid well and have much more vacation time than in Japan, which gives them the opportunity to read. Every bookstore I visited was bustling with people. In Japan, though, even buying books has become a struggle for many, and with such limited time off, it’s hard for people to find the time to read. I think this also points to issues in the political system. Lately, I’ve been constantly thinking about wages and vacation time.

INDEX

How the Japanese Literature Boom Aligns with the Book Club Culture

Earlier, you mentioned that there’s a trend where reading books by Japanese female authors is considered “cool.” How is BUTTER being received in this context?

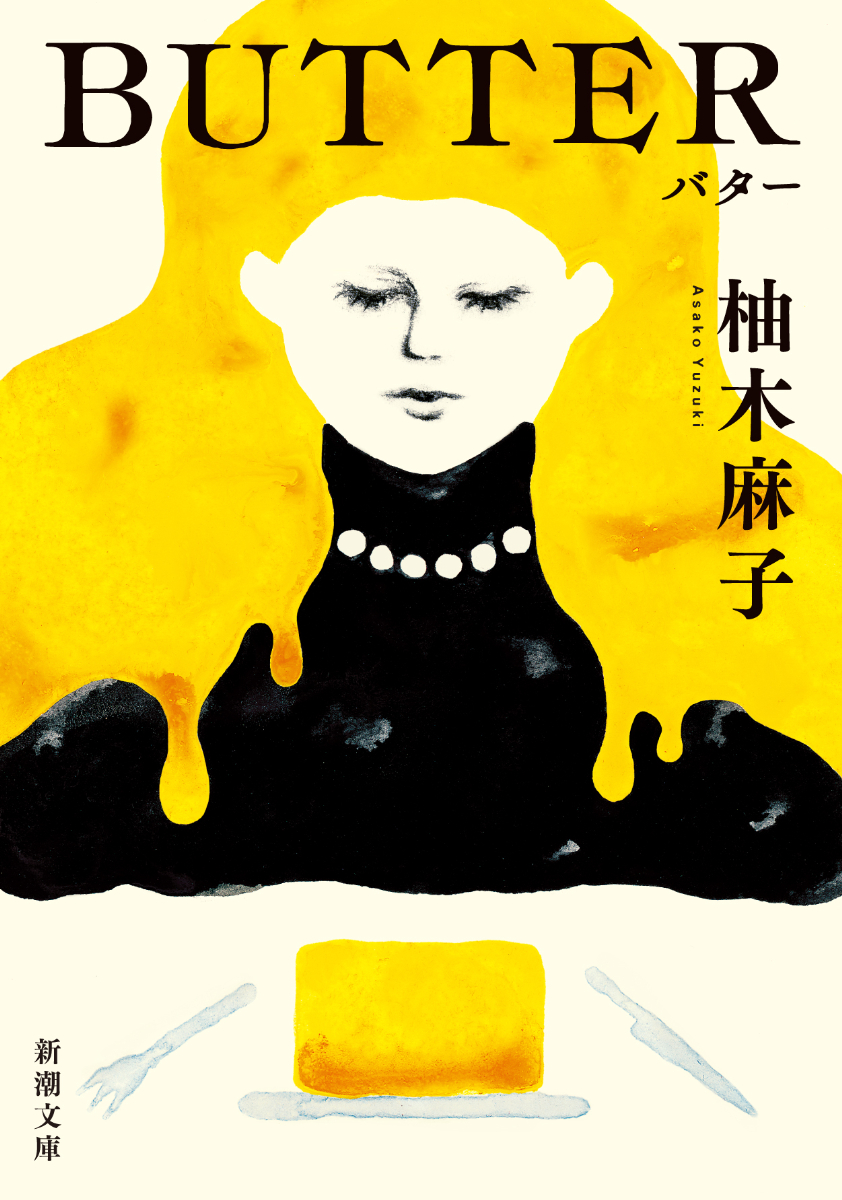

Yuzuki: In contrast to Japan, where it’s marketed differently, BUTTER is being sold overseas as a “feminist novel.” I think the only time the term “feminism” appeared on the cover in Japan was in an essay I wrote. I understand the sales strategy, but more often, the focus is shifted to something broader, like humanism, to appeal to a wider audience.

In the UK, however, it was clearly marketed as both feminist and cool. The tagline was simply a line from the book: “I hate feminism and margarine.” The same strategy was applied in Germany and the US as well.

That one line is what makes it “cool” for international readers.

Yuzuki: I intended it to be a humorous line, but it didn’t really get much of a laugh in Japan. However, in the UK, people found it hilarious. They really enjoy sarcasm, so the combination of a feminist novel with the title BUTTER and the line “I hate feminism and margarine” felt wickedly funny to them. Everywhere I went, people asked me to say that line, and they’d laugh each time.

The cultural differences really come through in moments like this.

Yuzuki: Exactly. Even what people find funny is different, and the way readers interpret the book as depicting the “struggles of men” varies too. In Japan, genres are often divided very precisely, so my book tends to be marketed as “empowering” there. But for some, it might actually feel like an unsettling story. Genre classification is tricky.

It’s like how movies are often marketed as “emotionally moving.” They slap on an easy-to-understand tagline, but the story itself can’t really be neatly categorized.

Yuzuki: Exactly. Abroad, it’s simply called a “novel.” I think people in other countries are more open to works that defy traditional genre boundaries. Also, the story’s setup, where the criminals involve detectives and reporters, is something people there really enjoy. That cultural background plays a big role as well.

Even though I read a lot of novels, when I’m in Japan, I sometimes feel like “I still have so much to learn” or “I can’t participate in certain discussions because I don’t know enough.” But when I’m abroad, it feels like “Anyone who loves books can join the conversation!” I think that’s part of the reason why book clubs are so popular.

I’ve heard that book clubs are popular everywhere.

Yuzuki: BUTTER has become quite popular in book clubs too. In Japan, there’s this idea that you have to be a serious reader to join, but overseas, as long as you’ve read the book, you’re good to go. The focus is really on exchanging thoughts and opinions. There’s a rich history of book clubs that makes it easy for everyone to get involved. It’s like with movies—you might hesitate, thinking, “What if I get scolded for not having seen a classic black-and-white film?”

Overseas, I don’t think there’s that feeling that just reading a book automatically makes you “superior.” It’s more about enjoying the conversation. I love seeing social media posts of book club gatherings where people are reading BUTTER while eating sticky snacks or sushi in unusual ways [laughs]. If it’s that casual, I think even we could have a book club.

INDEX

Examining the Struggles of BUTTER‘s Characters and the Different Forms of Comfort They Seek

In Japan, I feel like the book became a topic of discussion partly due to its connection to real-life events. However, on a more personal note, it made me reflect on the question, “What does a comfortable life mean to me?” through the three characters—Mariko Kajii (Kaji Mana), Rika, and Reiko. The different interpretations of comfort for each of them are particularly captivating. How did you approach creating these characters to explore these contrasts?

Yuzuki: Thank you for asking such a thoughtful question. I often get asked, “Do you have a message for all the women who are going through hard times right now?” and it really makes me think. As a writer, I wish I had those words to share, but part of why I write novels is because I don’t always have them. When it comes to writing about feminism and women’s rights, there’s often pressure to present an idealized version of someone who can save all women. This can make it difficult for some to identify as feminists. I can’t just say to someone who’s struggling, “Read this book”… so, I really appreciate this question.

For Rika, what she finds comfort in is success—she believes that’s what will bring her peace.

As a reporter for a weekly magazine, she’s relentlessly chasing after success by securing exclusive stories.

Yuzuki: She mistakenly believes that success will bring her comfort. But that’s not the case. Deep down, she feels responsible for her father’s death, and confronting this belief is what I think will lead her to a more fulfilling life. Specifically, it’s about understanding that dying alone isn’t something to fear, and realizing that she can live independently and happily until the end. It’s also about trying to live the way her father did, only to find out that it’s not necessarily an unhappy life. Perhaps, for her, true happiness lies in independence.

How about Reiko, Rika’s close friend, who is skilled in cooking and dreams of having a family?

Yuzuki: Reiko has complicated feelings toward her parents, so she sees creating a family as a way to find comfort. But in reality, her true comfort comes from being surrounded by partners and friends who respect her as a whole person, not just for her sexuality. While she focuses on the idea of family, I believe that Reiko could find her ideal life even outside of that structure.

As for Kaji Mana, she rejects women and believes that being adored by men is what brings her comfort.

Kaji Mana, the gourmet imprisoned in Tokyo Detention Center for allegedly killing three men after a series of marriage scams, has repeatedly spoken about the pleasure she gets from serving men.

Yuzuki: She thinks her sense of comfort comes from being detached from the struggles of other women. However, in reality, what Kaji Mana really wants is to make women say, “This is delicious! So delicious!” with her cooking. She isn’t trying to satisfy men’s appetites. What she wants is to use the money she’s taken from men to host and delight women, and there’s likely a maternal aspect to this desire. She craves the excitement of women praising her and saying, “As expected from Kaji Mana!” That’s why I believe Kaji Mana really liked Rika, who followed her food recommendations exactly.

Through their conversations in prison, Kaji Mana is essentially hosting Rika.

Yuzuki: Yes, that’s right. But since she can’t cook, all she can do is talk. For someone who loves cooking, being unable to make food is extremely frustrating, so Kaji Mana vents her feelings onto Rika. However, as Rika starts actually trying the dishes Kaji Mana recommends, she becomes happy, and I think she starts to see Rika as a true friend.

But once Rika starts getting closer to Reiko, Kaji Mana gets upset. It’s at that point that she thinks, “I’m really going to make her pay.” But honestly, I don’t think Rika will ever find another friend like Kaji Mana—someone who listens to her, follows her suggestions, and gives her honest feedback.

What was striking is how each character’s sense of comfort differs, even in terms of looks and appearance.

Yuzuki: Yes, their backgrounds are so different that their sense of comfort varies too. Rika, for example, has a low sense of beauty. In fact, she feels uncomfortable with her own attractiveness. On the other hand, Kaji Mana doesn’t think she’s unattractive at all. Her definition of beauty is “being abundant.” Being a rich, abundant woman is what she finds beautiful. In fact, Kaji Mana is the most free from the pressures of lookism.

Indeed, despite what society says, she firmly held onto her beliefs about beauty.

Yuzuki: Rika is tall and slender, and in her all-girls’ school, she was seen as a “prince” type. However, as she starts gaining weight, she begins to understand the kind of looks Kaji Mana has received throughout her life and what it means to maintain self-confidence. So, it might actually be Reiko who struggles the most with lookism. She is tormented by the gap between her own self-image and how others perceive her.