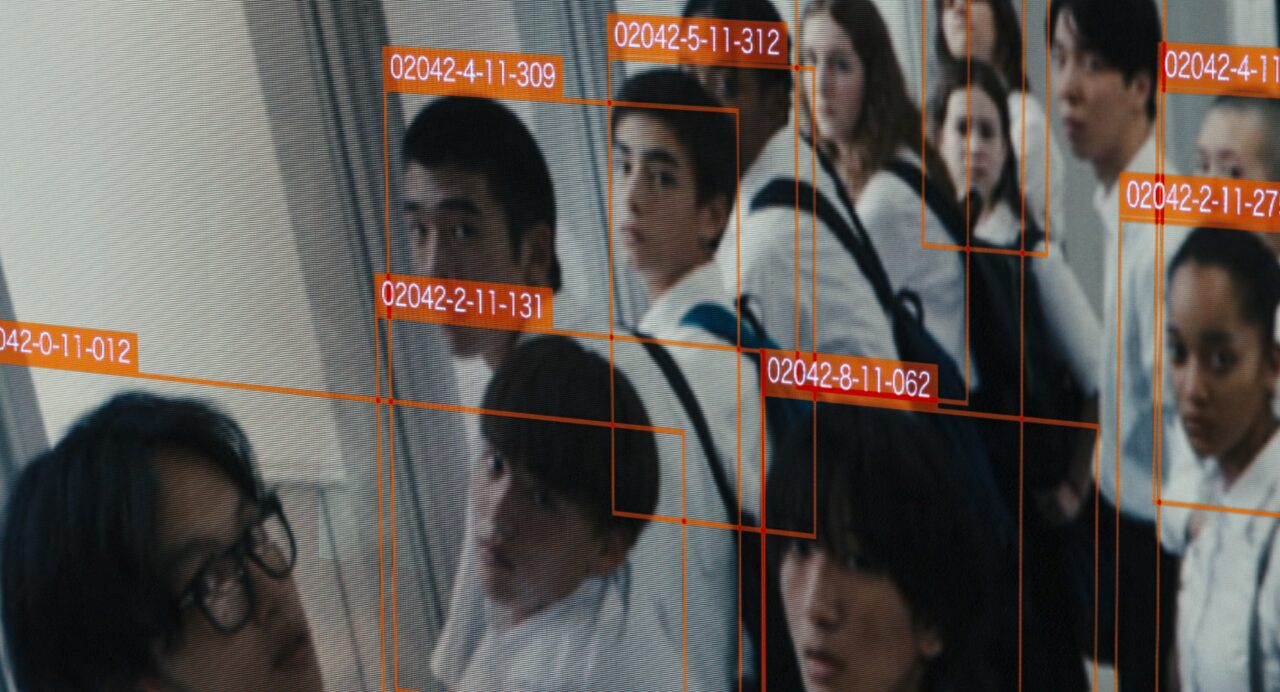

Neo Sora’s feature debut, HAPPYEND, is a masterpiece born from the chaos of the 2020s, offering a beacon of hope for the future of Japanese cinema. With its visual aesthetics reminiscent of 1990s Asian films, it delivers a sharp critique of modern Japanese society while also engaging a global audience with thought-provoking questions.

At its core, this challenging film is anchored in the universal theme of friendship. It successfully navigates the balance of being political without excluding viewers based on ideology. To uncover the deeper layers of the film, we interviewed Kimi Idonuma, a close friend of the director. Our conversation explored how the film captures emotions like love, friendship, and the full range of human feelings that transcend notions of “social correctness.”

INDEX

Born in the U.S. and raised in both Japan and the U.S., Neo Sora is a filmmaker, artist, and translator based in New York and Tokyo. In 2024, he directed the concert documentary ‘Ryuichi Sakamoto | Opus,’ which, despite its simple and austere direction focusing solely on piano performances, has garnered critical acclaim at film festivals worldwide, following its world premiere at the Venice International Film Festival. It has since been screened at festivals in Yamagata, Busan, New York, London, and Tokyo. In October 2024, his feature film debut, ‘HAPPYEND,’ will be released.

Capturing Anger Through the Art of Film

At the beginning of the film, the words “The forces trying to confine people to old frameworks are loud” are displayed, and right after that, a red light appears. That made me feel like this film might place importance on the theme of “anger.” As I continued watching, that feeling gradually turned into certainty. Was anger something you consciously focused on while making this film?

Sora: Yes, it was. I believe anger is important. The fact that you can get angry at something shows that you still have hope for it, right? If you’d already given up or didn’t care at all, you probably wouldn’t even feel the need to get angry.

I think anger is a deeply important form of expressing love, whether on a personal level or a societal one. That’s why I sometimes feel like it isn’t right to suppress it.

When trying to convey anger to someone, it’s often difficult to choose the right words, but sometimes expressing it leads to better outcomes. On the other hand, in my daily life, I often find myself feeling irritated but not quite reaching the level of full anger. So, I’m curious how you personally deal with anger in your everyday life.

Sora: I’m the type to simmer slowly. I don’t usually explode, and it takes me a while to understand my own emotions, so I’m not very quick to react. That’s why I tend to mull things over, let my anger simmer, and then channel it into writing or making films.

Some people can explode in anger within seconds, while others take days, weeks, or even years to express it. Everyone has their own way of dealing with it. HAPPYEND seems to capture that full gradient of emotions. For example, there’s a scene where Kou and Yuta have a heated argument, but right after that, we see a simple, almost peaceful moment where they’re working together, moving things.

Sora: In that scene, I was thinking about what it feels like when a couple argues. I think a lot of people have experienced this, but during an argument, it often feels like time skips ahead. One moment you’re shouting, and the next, your relationship has somehow started to mend itself. It’s like, “How did we get to this point where we were yelling?” and “Where did the in-between moments go?” I wanted to capture that subjective experience in the film, so I intentionally skipped over part of the scene.

That’s fascinating. There were many other moments of playful shooting and editing throughout the film, too. It felt like you were having fun making it.

Sora: I was definitely conscious of that. I gave myself a challenge during the shoot. Of course, every scene has a plot point to hit and something to convey, but I also wanted to add something that would create a sense of cinematic joy in each moment.

It’s a bit vague when I try to put it into words, but it could be something as simple as a visual gag, a focus on sound, attention to the beauty of a shot, or playful editing. My goal was to infuse every scene with something that evokes the joy of cinema.

This incident leads Kou to start reflecting deeply on the discomfort he’s been feeling toward his identity and society. On the other hand, Yuta just wants to keep having fun with his friends like they always have. As a result, the once-close relationship between the two begins to grow strained.

INDEX

Training to Evoke Emotions: A Practice in Rebellion Against the Mundane

I wondered if the emotion of “joy” might somehow connect with the “anger” we talked about earlier. I have the impression that Neo has a remarkable ability to enjoy things and find humor in them. Perhaps this is because he regularly engages with a full range of emotions, keeping his emotional muscles relaxed.

Sora: That makes me remember that I tend to think of every experience as something to be grateful for. It might be a bit of a professional habit, but even when faced with really unpleasant feelings or events, I find myself thinking, “I’ve never felt this way before.”

Recently, I experienced the death of my father. It was incredibly sad, and being present at that moment was shocking. But it’s a once-in-a-lifetime experience. It may sound strange, but I’ve realized that I feel grateful to have had that experience. There’s a part of me that appreciates that my emotions have been stirred in a way I’ve never felt before.

When did you start thinking, “I’m glad to have experienced this emotion”?

Sora: I think it was in middle school or high school. During that time, I had a phase where I intentionally watched videos that made me feel “pain.”

Why did you do that?

Sora: Because I wanted to know.

You wanted to understand painful emotions?

Sora: Exactly.

For example, what kind of things did you watch?

Sora: Hmm, back then, YouTube was just emerging, and there weren’t many content restrictions. I was watching videos of surgeries and real footage from battlefields. I wasn’t enjoying it; in fact, I didn’t really want to see it, but I convinced myself that it was my responsibility to be aware of these things happening in the world! It sounds really intense when I say it like that [laughs].

-[laughs].

Sora: But there was a time when I was trying to consume things through media that I could never experience in my daily life. There are so many events happening around the world that I can’t experience everything, and I don’t have the courage to seek out some of those experiences. Still, I wanted to know as many different emotions as possible.

Sora: That’s one of the main reasons I started going to the movies more often. Of course, it’s not just about the unpleasant things; when I watch a romantic film, I can discover wonderful feelings of love that I’ve never experienced. I also really enjoy hearing how others felt about what they watched. This desire to accumulate various emotions began during my student days.

It sounds like a practice in stirring emotions. I remembered that you wrote in the press materials for ‘HAPPYEND,’ “If you don’t build your emotional muscles, you won’t be able to act when you find yourself in a situation where you need to break significant rules or laws.”

Sora: From the small, everyday level, when I encounter things I find meaningless or harmful, I call the act of rebelling against and dismantling them “anarchist calisthenics.” I believe it’s really important to take direct action to change things rather than just accepting them when faced with the trivial. In the film, Yuta unconsciously embodies this kind of natural rebellion, but I think it would be even better if he could do it with greater awareness.

Sora: If we don’t become aware, we can’t properly resist the structural violence that is often hidden on the surface. At the same time, it’s important not just to be aware, but also to actively rebel against and dismantle these structures. Otherwise, when faced with conscription or laws and systems that lead people toward war and genocide, we won’t be able to fight back.

I believe that if we don’t continue to cultivate a “thinking ability that follows oneself” rather than just the system, Japan will end up complicit in wars and will become entangled in them. We won’t even be able to recognize the violent structures that already exist in Japanese society. For example, people paying into the pension system in Japan are unknowingly having their money invested in Israeli government bonds and defense contractors. We are definitely in a position where such global issues are at play.

INDEX

Anger as a Sign of Affection

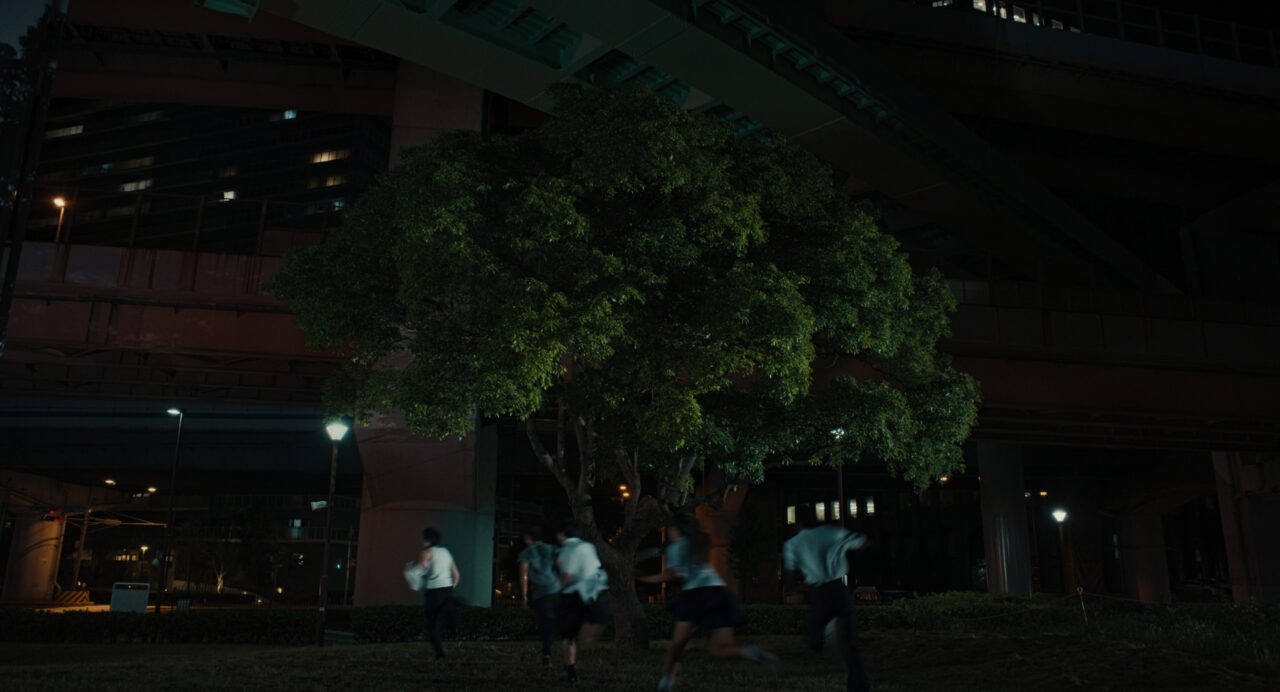

In ‘HAPPYEND,’ there are repeated small acts of rebellion and resistance, such as taking off their school uniforms to enter a club. The scene where a single tree is shown after the protagonists have run away also feels like a rebellion against large corporations that continue to cut down trees for profit, and I really appreciated those kinds of details.

Sora: Thank you.

Editor Yamamoto: Speaking of rebellion and resistance, one thing that really stood out to me in this film was how techno music was used symbolically. I loved how ‘HAPPYEND’ naturally incorporates techno as a “music of resistance” in a coming-of-age film.

Sora: Techno was created by Black residents of Detroit during the economic recession following the decline of the auto industry. They made the music to keep themselves dancing. Hip-hop, rock, and many music genres are deeply connected to Black culture in some way, and techno is no different. There’s a strong sense that we borrowed from music created for liberation.

In Japan, there’s this otaku-like quality where people masterfully adopt techno, hip-hop, and rock, but it’s often severed from its original political context and transformed into a mere commodity for consumption. That’s something I find really disappointing. I’d rather see people inherit the spirit behind the music instead.

Editor Yamamoto: In ‘HAPPYEND,’ the characters embody the spirit of techno. What really moved me was how Yuta and Kou take a DIY approach and create their own party space, for themselves and by themselves.

Sora: That’s the true spirit of techno and direct action.

I think it takes a lot of courage to translate feelings of resistance and rebellion into action, which is why we need to prepare ourselves in our daily lives.”

Sora: Being aware of past instances of resistance and rebellion can also be empowering. For example, I really like the story about a bench in Tennessee. The city removed the bench because homeless people were sleeping on it. An artist, thinking, ‘That’s just wrong,’ placed a beautifully painted bench where anyone could sit, without asking for permission. Naturally, the city tried to remove it, but when a video of this situation was made, citizens protested, asking, “Why are you removing it? It was such a beautiful bench!”

I think this is, in a sense, a very revolutionary event. It shows that individuals act not because they were asked to, but because they believe it’s necessary.

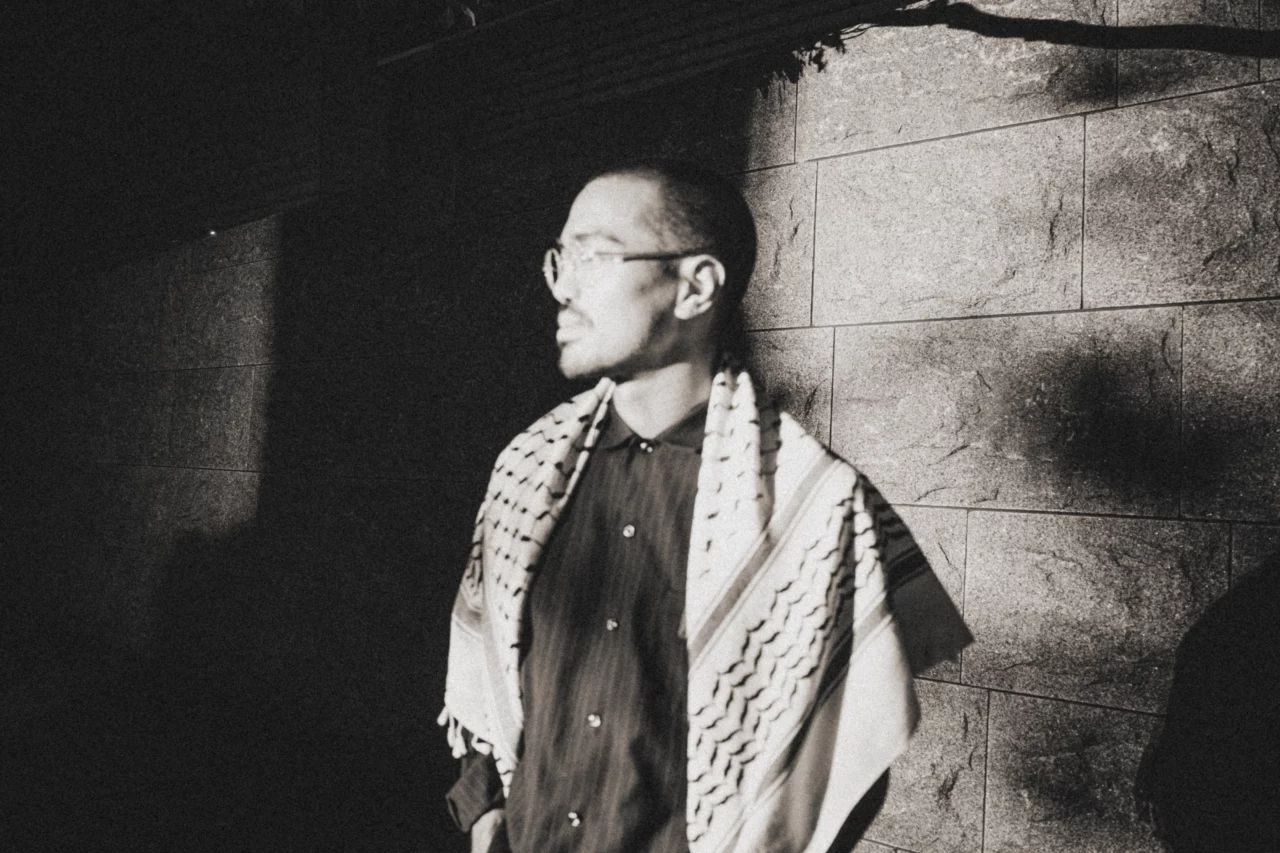

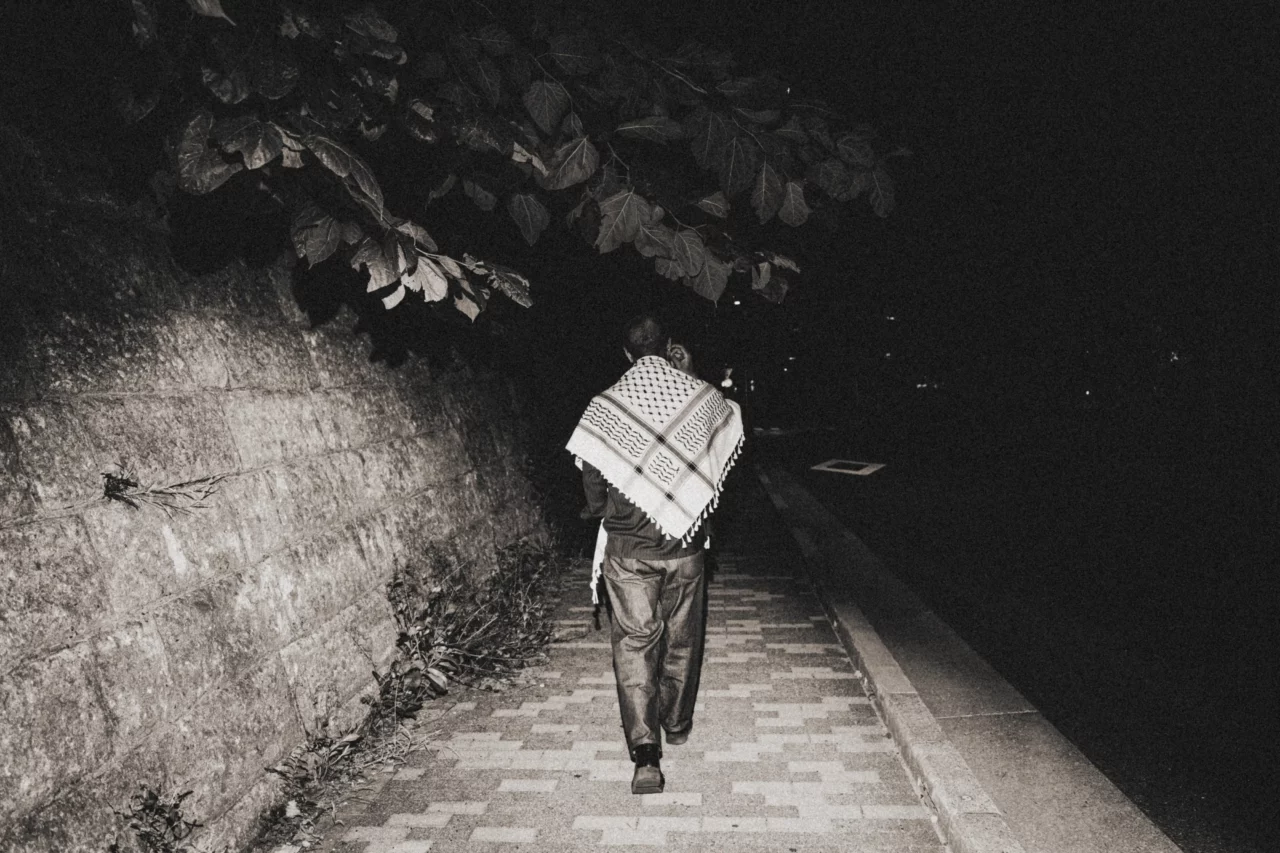

Growing up in a culture where ‘obediently following rules makes you a model student,’ it’s easy to have a negative view of those who resist and rebel. However, as seen with the bench example, there are often legitimate desires behind such actions. When I saw Sora receiving applause at the Venice International Film Festival while wearing a Palestinian flag pin and a keffiyeh (a traditional Palestinian scarf), I felt encouraged by both his actions and the reactions they provoked.

Sora: I participate in many demonstrations in Japan, and sometimes I hear people mutter, “That’s scary.” I can understand that for someone who isn’t grasping the situation, a group shouting in the streets might seem frightening.

However, if they came even once and listened to what we’re saying, they’d realize that those people are some of the kindest around. If they weren’t kind, they wouldn’t sacrifice their precious time to stand on the street every day in the scorching summer, shouting “Don’t kill children.”

Sora: I believe that those who demonstrate for Palestine are some of the kindest people. It might be similar to the idea that anger is a form of love; the fact that they shout comes from a place of love and kindness, and I want more people to understand that.

Also, I mentioned earlier that I want to know various emotions, but I no longer want to see videos of the massacre of Palestinians that flow across my phone screen. While I can turn off my phone and distance myself from that reality, the Palestinians in Gaza have to continue living that reality. It’s unforgivable. I truly want the massacre to stop. That’s why I shout for it to end and take concrete actions to make it happen.

INDEX

Friendship and love as catalysts for miracles in ‘HAPPYEND’

Can you share your thoughts on the aspect of love in this film, which is closely tied to anger? When I met Neo right after the filming of HAPPYEND, I distinctly remember him showing a photo of the cast embracing each other and joyfully saying, “It was genuinely the best experience.” Watching the film itself, I found myself loving each character, and I was curious about how such a profoundly affectionate work was created.

Sora: (pulling out his phone) Is this what you mean?

Sora: This is a photo taken right after we finished shooting the last cut. The chief assistant director arranged for the scene with all the cast to be filmed at the very end.

It’s a truly amazing photo.

Sora: There are many reasons why this film was able to come together, but a big part of it is that I have deep affection for my friends from my student days, who were also a source of inspiration for this project.

I’m making this film by borrowing from my relationships and experiences with them, and I genuinely love them. I wouldn’t be who I am today without them, and even if we haven’t seen each other for years, when I go back to NY, we can talk just like we always do. Even though I don’t talk much with my university friends who were politically separated from me, I still love them. I believe HAPPYEND was born from remembering them while creating it.

That’s wonderful.

Sora: On a practical level, I’m not a perfectionist, and I can’t use my staff in a military way to fulfill my vision. So, I was conscious of creating an environment where everyone involved could come up with as many good ideas as possible. Plus, I just really don’t like scary people, so I tried not to be one myself [laughs].

Four out of the five main cast members have no acting experience. How did you approach directing them?

Sora: My guiding principle was to help them feel as much like themselves as possible within the imaginary setting. Being “yourself” on set is actually incredibly challenging. It requires a significant amount of trust and relaxation among each other, so I aimed to create a situation where the five of them could naturally become friends.

In reality, they far exceeded my expectations, and a big part of it was that they became friends on their own. By the time we started rolling the camera, their relationships were already somewhat established.

By the way, what plan did Sora have in mind for helping the five get along?

Sora: We started workshops two months before filming, creating time and space for them to work together. This was something I began on the advice of Ryūsuke Hamaguchi. At that time, Mina’s actor, Sina Pen, was still in New York, so we would meet over Zoom two or three times a week. We introduced ourselves and played a game where we would each weave a single lie into our conversation. We also shared one topic we were passionately interested in and could talk about for hours.

Once Sina arrived in Japan a month before filming, we rented a community center two or three times a week for rehearsals and workshops. We increased physical closeness during the workshops and discussed what acting is. We did various activities, but the content wasn’t as important as creating time to do something together.

Sora: After the workshop, I had to head home for another task, but the cast members went out to eat together on their own. I think that’s where their friendships really deepened. I merely created the opportunity; they did the actual work of getting close.

While watching the movie, I grew to love the five of them like they were my own friends.

Sora: Recently, during the screening of ‘HAPPYEND’ in Venice, there was a wonderful moment. Hayato Kurihara, who plays Yuuta, arrived a bit late, and the moment he showed up, Yuki Hi daka, who plays Kou, started crying tears of joy.

What a miraculous team.

Sora: It truly is miraculous, and this is something you just can’t plan! I sincerely believe that the movie exists because of their relationships.

HAPPYEND

Nationwide Release on Friday, October 4, 2024, at Shinjuku Piccadilly, Human Trust Cinema Shibuya, and other theaters

Director & Screenplay: Sora Neo

Cast:

Hayato Kurihara

Yuki Hidaka

Yuta Hayashi

Shina Pen

ARAZI

Kilala Inori

Ayumu Nakajima

Masaru Yahagi

PUSHIM

Makiko Watanabe

Shiro Sano

Cinematography: Bill Killstine

Art Direction: Norifumi Ataka

Music: Lea Ouyuyan Rusli

Sound Supervisor: Miki Nomura

Producers: Albert Toren, Aiko Masubuchi, Eric Niarri, Alex Law, Anthony Chen

Production & Development: ZAKKUBALAN, CineLiq Creative, Cinema Inutile

Distribution: Bitters End

© 2024 Music Research Club LLC