Neo Sora’s feature debut, HAPPYEND, is a masterpiece born from the chaos of the 2020s, offering a beacon of hope for the future of Japanese cinema. With its visual aesthetics reminiscent of 1990s Asian films, it delivers a sharp critique of modern Japanese society while also engaging a global audience with thought-provoking questions.

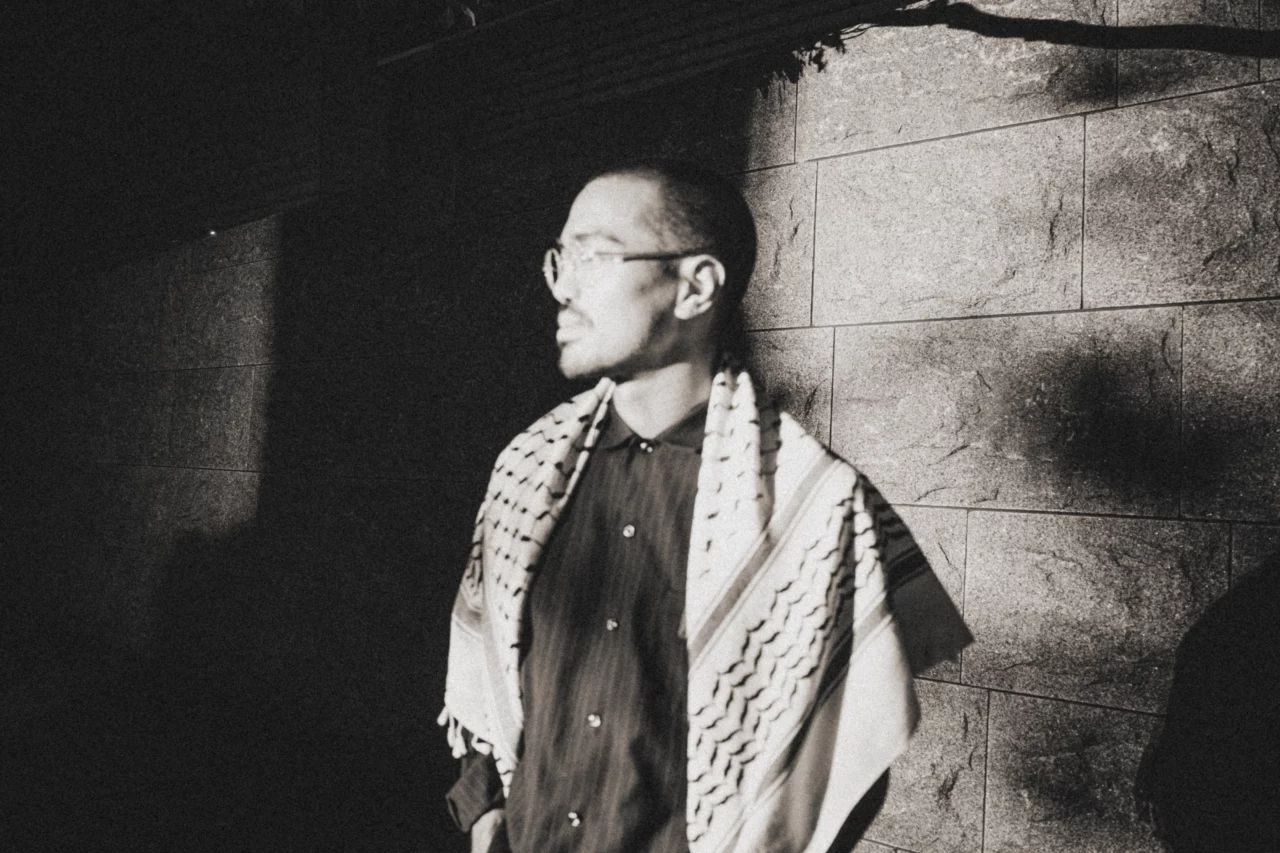

At its core, this challenging film is anchored in the universal theme of friendship. It successfully navigates the balance of being political without excluding viewers based on ideology. To uncover the deeper layers of the film, we interviewed Kimi Idonuma, a close friend of the director. Our conversation explored how the film captures emotions like love, friendship, and the full range of human feelings that transcend notions of “social correctness.”

INDEX

Born in the U.S. and raised in both Japan and the U.S., Neo Sora is a filmmaker, artist, and translator based in New York and Tokyo. In 2024, he directed the concert documentary ‘Ryuichi Sakamoto | Opus,’ which, despite its simple and austere direction focusing solely on piano performances, has garnered critical acclaim at film festivals worldwide, following its world premiere at the Venice International Film Festival. It has since been screened at festivals in Yamagata, Busan, New York, London, and Tokyo. In October 2024, his feature film debut, ‘HAPPYEND,’ will be released.

Capturing Anger Through the Art of Film

At the beginning of the film, the words “The forces trying to confine people to old frameworks are loud” are displayed, and right after that, a red light appears. That made me feel like this film might place importance on the theme of “anger.” As I continued watching, that feeling gradually turned into certainty. Was anger something you consciously focused on while making this film?

Sora: Yes, it was. I believe anger is important. The fact that you can get angry at something shows that you still have hope for it, right? If you’d already given up or didn’t care at all, you probably wouldn’t even feel the need to get angry.

I think anger is a deeply important form of expressing love, whether on a personal level or a societal one. That’s why I sometimes feel like it isn’t right to suppress it.

When trying to convey anger to someone, it’s often difficult to choose the right words, but sometimes expressing it leads to better outcomes. On the other hand, in my daily life, I often find myself feeling irritated but not quite reaching the level of full anger. So, I’m curious how you personally deal with anger in your everyday life.

Sora: I’m the type to simmer slowly. I don’t usually explode, and it takes me a while to understand my own emotions, so I’m not very quick to react. That’s why I tend to mull things over, let my anger simmer, and then channel it into writing or making films.

Some people can explode in anger within seconds, while others take days, weeks, or even years to express it. Everyone has their own way of dealing with it. HAPPYEND seems to capture that full gradient of emotions. For example, there’s a scene where Kou and Yuta have a heated argument, but right after that, we see a simple, almost peaceful moment where they’re working together, moving things.

Sora: In that scene, I was thinking about what it feels like when a couple argues. I think a lot of people have experienced this, but during an argument, it often feels like time skips ahead. One moment you’re shouting, and the next, your relationship has somehow started to mend itself. It’s like, “How did we get to this point where we were yelling?” and “Where did the in-between moments go?” I wanted to capture that subjective experience in the film, so I intentionally skipped over part of the scene.

That’s fascinating. There were many other moments of playful shooting and editing throughout the film, too. It felt like you were having fun making it.

Sora: I was definitely conscious of that. I gave myself a challenge during the shoot. Of course, every scene has a plot point to hit and something to convey, but I also wanted to add something that would create a sense of cinematic joy in each moment.

It’s a bit vague when I try to put it into words, but it could be something as simple as a visual gag, a focus on sound, attention to the beauty of a shot, or playful editing. My goal was to infuse every scene with something that evokes the joy of cinema.

This incident leads Kou to start reflecting deeply on the discomfort he’s been feeling toward his identity and society. On the other hand, Yuta just wants to keep having fun with his friends like they always have. As a result, the once-close relationship between the two begins to grow strained.

INDEX

Training to Evoke Emotions: A Practice in Rebellion Against the Mundane

I wondered if the emotion of “joy” might somehow connect with the “anger” we talked about earlier. I have the impression that Neo has a remarkable ability to enjoy things and find humor in them. Perhaps this is because he regularly engages with a full range of emotions, keeping his emotional muscles relaxed.

Sora: That makes me remember that I tend to think of every experience as something to be grateful for. It might be a bit of a professional habit, but even when faced with really unpleasant feelings or events, I find myself thinking, “I’ve never felt this way before.”

Recently, I experienced the death of my father. It was incredibly sad, and being present at that moment was shocking. But it’s a once-in-a-lifetime experience. It may sound strange, but I’ve realized that I feel grateful to have had that experience. There’s a part of me that appreciates that my emotions have been stirred in a way I’ve never felt before.

When did you start thinking, “I’m glad to have experienced this emotion”?

Sora: I think it was in middle school or high school. During that time, I had a phase where I intentionally watched videos that made me feel “pain.”

Why did you do that?

Sora: Because I wanted to know.

You wanted to understand painful emotions?

Sora: Exactly.

For example, what kind of things did you watch?

Sora: Hmm, back then, YouTube was just emerging, and there weren’t many content restrictions. I was watching videos of surgeries and real footage from battlefields. I wasn’t enjoying it; in fact, I didn’t really want to see it, but I convinced myself that it was my responsibility to be aware of these things happening in the world! It sounds really intense when I say it like that [laughs].

-[laughs].

Sora: But there was a time when I was trying to consume things through media that I could never experience in my daily life. There are so many events happening around the world that I can’t experience everything, and I don’t have the courage to seek out some of those experiences. Still, I wanted to know as many different emotions as possible.

Sora: That’s one of the main reasons I started going to the movies more often. Of course, it’s not just about the unpleasant things; when I watch a romantic film, I can discover wonderful feelings of love that I’ve never experienced. I also really enjoy hearing how others felt about what they watched. This desire to accumulate various emotions began during my student days.

It sounds like a practice in stirring emotions. I remembered that you wrote in the press materials for ‘HAPPYEND,’ “If you don’t build your emotional muscles, you won’t be able to act when you find yourself in a situation where you need to break significant rules or laws.”

Sora: From the small, everyday level, when I encounter things I find meaningless or harmful, I call the act of rebelling against and dismantling them “anarchist calisthenics.” I believe it’s really important to take direct action to change things rather than just accepting them when faced with the trivial. In the film, Yuta unconsciously embodies this kind of natural rebellion, but I think it would be even better if he could do it with greater awareness.

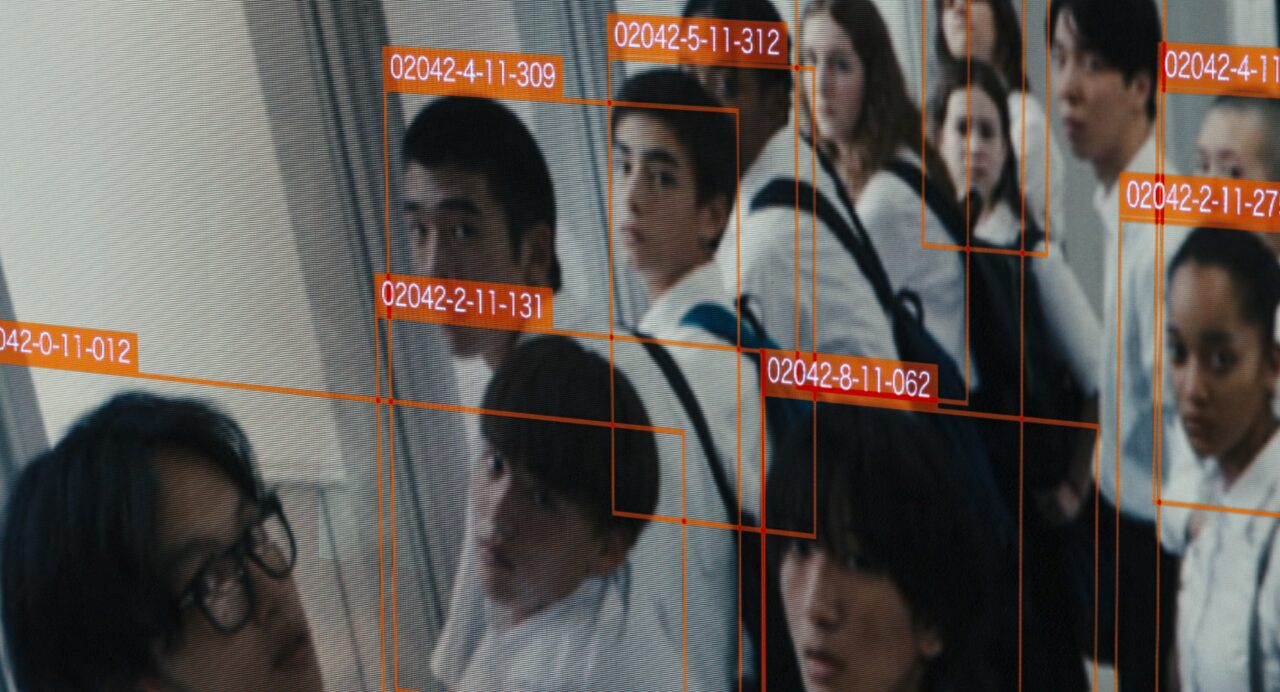

Sora: If we don’t become aware, we can’t properly resist the structural violence that is often hidden on the surface. At the same time, it’s important not just to be aware, but also to actively rebel against and dismantle these structures. Otherwise, when faced with conscription or laws and systems that lead people toward war and genocide, we won’t be able to fight back.

I believe that if we don’t continue to cultivate a “thinking ability that follows oneself” rather than just the system, Japan will end up complicit in wars and will become entangled in them. We won’t even be able to recognize the violent structures that already exist in Japanese society. For example, people paying into the pension system in Japan are unknowingly having their money invested in Israeli government bonds and defense contractors. We are definitely in a position where such global issues are at play.