For thirty years, Shunji Iwai has been quietly revolutionizing Japanese cinema. With films like Love Letter, Hana and Alice, and All About Lily Chou-Chou, he has created a body of work defined not by spectacle, but by atmosphere — a world suspended delicately between reality and reverie. His unique cinematic language, shaped by soft natural light, flowing landscapes, and carefully chosen music, has earned the nickname “Iwai aesthetics,” and has resonated deeply with audiences far beyond Japan.

At the heart of Iwai’s films is a deep sensitivity to sound and music. Whether it’s the melancholy swell of strings, the echo of silence in a snowy town, or the undercurrent of classical themes, music in his work is never ornamental — it is narrative. Collaborating closely with composer Takeshi Kobayashi, Iwai created what he calls “music films,” most famously Swallowtail Butterfly, and has since remained deeply involved in music not only through his film scores but also as the founder of music units like Hekuto Pascal and ikire.

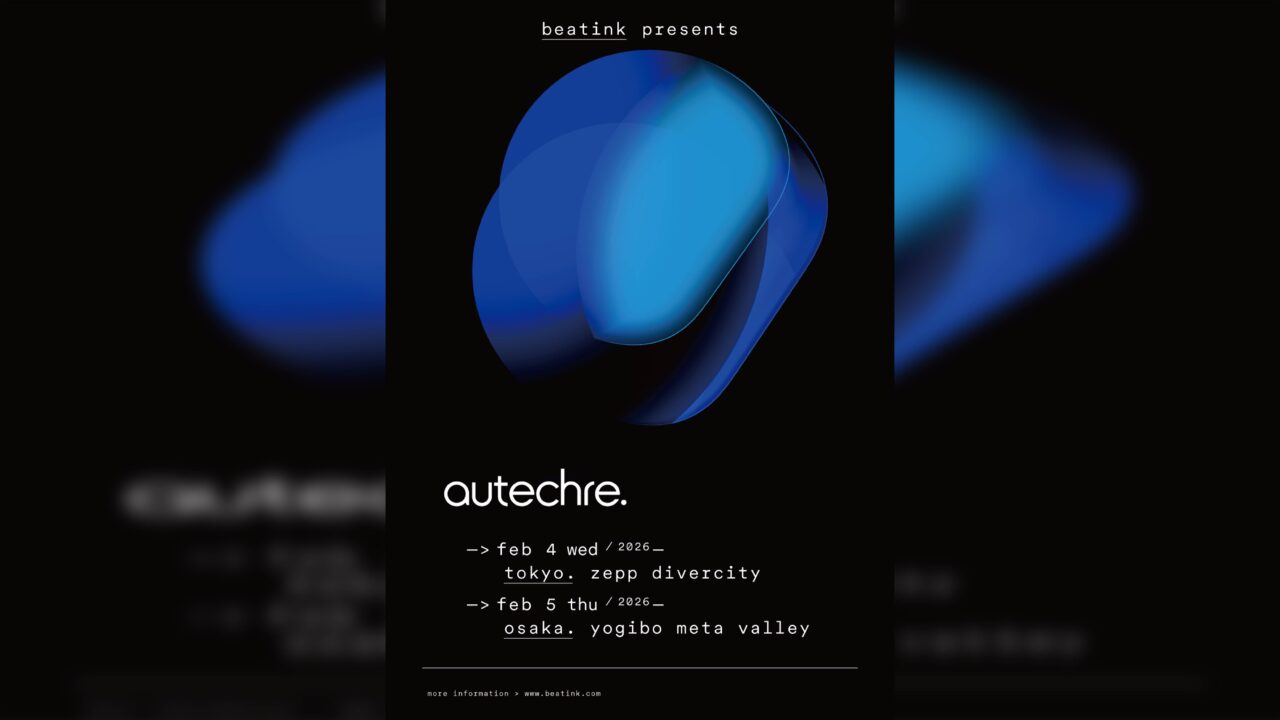

Now, as he celebrates the 30th anniversary of his directorial debut, Iwai returns to the film that started it all: Love Letter. In a special one-night-only performance, he brings the score to life on stage, inviting audiences to experience the emotional core of the film through live music. Ahead of this event, we sat down with Iwai to reflect on his musical roots, the intimate relationship between image and sound, and how three decades of filmmaking have shaped the way he listens—to the world, and to himself.

INDEX

The Music Behind Shunji Iwai’s Early Memories: Osamu Tezuka’s Mushi Production and the Carpenters

Your film scores have a distinct, consistent feel. Can you describe the musical landscape of your earliest influences?

Iwai: Fundamentally, I don’t think it’s changed much. The music I’ve loved since I was a child remains largely the same, and when I listen to it now, I realize that the chord progressions I’m drawn to have been a constant presence.

What kinds of music have truly moved you over the years?

Iwai: It’s not so much about specific genres or individual songs, but rather that the chord progressions in the music I connect with share certain patterns. I only became aware of this later on. Honestly, I’m not sure why these progressions resonate with me, but they’ve been with me since childhood.

A visionary filmmaker, novelist, and composer born on January 24, 1963, in Miyagi Prefecture. Iwai first captured attention in 1993 with his innovative omnibus drama Fireworks, Should We See It from the Side or the Bottom?, earning the Directors Guild of Japan’s New Directors Award. His 1995 debut feature Love Letter resonated deeply across Asia, establishing him as a unique voice in contemporary cinema. Over the years, Iwai has continued to craft poetic, atmospheric works that blur the lines between reality and memory, securing his place as one of Japan’s most influential storytellers.

So rather than following popular trends, you trusted your own instincts about what music spoke to you?

Iwai: Exactly. As a child, I often listened to music from anime made by Osamu Tezuka’s Mushi Production. When I got to elementary school, kayōkyoku — the popular Japanese songs of the time — were everywhere, and I heard them naturally. But to me, the music from Mushi Pro felt more rich and layered. Looking back, it contained jazz influences and more modern chord progressions.

Your generation grew up during the heyday of folk and kayōkyoku, with music programs thriving on TV, correct?

Iwai: That’s right. But watching those music shows was almost painful for me. I had a kind of aversion to the music playing at home and in public spaces. Since we were somewhat forced to watch TV, it became a bit of a trauma. Then, in upper elementary school, I started listening to artists like the Carpenters and Yumi Matsutoya, which reignited my connection to music — but even then, the number of songs I truly liked was quite limited.

Did you listen to a lot of music actively to find songs that really resonated with you?

Iwai: I don’t think I was that proactive. But since I wasn’t influenced much by my parents, I guess I found music here and there on my own. I also liked soundtracks from Western films. When I was in elementary school, I would sometimes listen to collections of Western movie soundtracks and discover songs that way, or occasionally hear a piece from a foreign film I happened to catch on TV. I preferred simple arrangements — like just piano — rather than lavish, grandiose ones.

INDEX

A Chance Encounter with Takeshi Kobayashi Through the Car Radio

Your films Swallowtail Butterfly (1996), All About Lily Chou-Chou (2001), and Kyrie (2023) are often called “music films,” all featuring music by Takeshi Kobayashi. What was it about his music that resonated with you?

Iwai: I was writing the script for Swallowtail Butterfly around 1994, right as the ’80s were ending. The ’80s were dominated by electronic instruments, especially electronic drums, which gave music a heavy, reverberant sound.

But in the ’90s, there was a shift toward drier, more stripped-down sounds, and that’s the vibe I connected with. I was listening a lot to American Motown records and ’70s artists like Carole King, so I wanted that kind of dry, intimate tone in the music. I was thinking about who could create that sound with me. Then one day, I heard “My Little Lover” playing on the car radio, and it immediately struck a chord. Since I’d directed music videos for Japanese band Southern All Stars, I knew Takeshi Kobayashi and felt there was a natural connection. Our musical tastes weren’t far apart at all.

How did you and Kobayashi collaborate on the music production?

Iwai: For Swallowtail Butterfly, we worked out of Kobayashi’s studio in New York, which featured analog amps and hired studio musicians — it was quite a lavish environment. We even went somewhere in Europe to record the orchestra. I guess that was the bubble era. The editing was done in Los Angeles as well. But for All About Lily Chou-Chou and Kyrie, the whole process took place more conventionally in Tokyo.

You started taking on the music yourself with Hana and Alice (2004), correct?

Iwai: Yes, I’ve always loved music since my student days and used to compose pieces for my indie films, but compared to professionals, I was nowhere near their level. For my early films like Love Letter (1995) and Picnic (1996), the music was done by REMEDIOS, and for Swallowtail Butterfly, I entrusted the score to Takeshi Kobayashi. I never really considered composing film music myself back then.

So how did you begin creating music on your own?

Iwai: One December, on a whim, I went to Yamaha’s Shibuya store and, with the staff’s help, picked up some software and a keyboard to make music on my PC. It started as a hobby, just playing around. The first piece I created was an arrangement of “Love Ballad” from The Inugami Curse [laughs]. I found it so enjoyable that every weekend I’d sit at my computer, composing music without any particular goal. The sound quality was impressive — the Roland SC-88. Later I learned that Ray HaraKami also used the same equipment, which thrilled me. The piano and acoustic guitar sounds were especially beautiful. Back in my student days, the sequencing gear I had just couldn’t produce such polished sounds no matter how hard I tried. After ten years, I was amazed at how far I’d come.

What prompted you to start composing music for your own films?

Iwai: It actually began with a commercial. It starred Takuya Kimura and was a parody of the Kindaichi Kosuke detective series. I created music inspired by The Inugami Family style for it. But I really started composing seriously with the soundtrack for April Story (1998). That took about three months. I felt confident then that if I took the time, I could make music myself.

Iwai: In the beginning, I worked under different pseudonyms, changing my pen name with each project. Eventually, JASRAC asked me to stop switching names so often, so I figured I might as well just use my real name.

You composed the entire soundtrack for Hana and Alice (2004), and its poignant, beautiful melodies left a strong impression.

Iwai: Thanks. Comedy scores are actually quite demanding because they require a wide range of styles. I aimed to base it on a classical tone, so I did a lot of research — listening, studying, and experimenting as I went. Around that time, I became obsessed with digital music programming, trying to replicate acoustic instruments on the computer. I tested countless sound libraries, rejected most of them, and kept searching endlessly for the perfect sounds… and yes, I spent quite a bit in the process.

INDEX

Embracing Works as “Products” with a Focus on “Quality Control” Through Universality

Did you have any specific preferences or philosophies in your approach to music production?

Iwai: Because films already include sound effects and dialogue, I prefer to keep the music as free from unnecessary noise as possible. Even with classical works like Debussy’s, I’ve sometimes rearranged loud sections marked forte or fortissimo into very soft pianissimo passages. When it comes to sound, I’d say I lean toward minimalism.

Iwai: Because Hana and Alice was a comedy, we incorporated woodwind and brass instruments, but at its core, I believe piano and cello are enough to carry most scenes. That’s especially true for Vampire (2012). The music I create tends to be very simple and ambient. Recently, I’ve been experimenting with sounds that can play continuously in the background without ever feeling intrusive.

Whether working with collaborators or composing on your own, is there a particular focus you maintain when creating film music?

Iwai: I always try to attune myself to what the visuals are calling for. That’s the sense I prioritize.

Iwai: Rather than music that clearly smells like it was made “specifically for this film,” I actually prefer when an existing piece unexpectedly fits perfectly. That’s my ideal.

When I create, I’m always aware of the “presence” or “essence” of the work. This applies not only to films and music but also to writing novels. By “presence,” I mean how the work will be perceived and displayed once it’s released. From that standpoint, it’s less of an “artwork” and more like a “product.” Without that product perspective, it’s easy to get lost in self-indulgence. So, I’m quite conscious about maintaining the quality control of the “product.”

Given the strong, unique world your films create, I found it surprising to hear you talk about “product management” instead of just calling them “works of art.”

Iwai: If you label everything as a “work,” then everything — good or bad — is just a “work.” The products around me feel natural to use because someone guarantees their quality. But if the quality is poor, consumers immediately think, “What is this?” No product simply exists by chance; it’s created by a team of dedicated makers who care deeply about quality.

I always thought films were more about being “artworks,” unlike everyday products.

Iwai: Everyday products are meticulously managed down to every single part and produced under strict standards. That level of care and quality control should be the basic premise for films as well.

INDEX

Leaving Even a Fragment in Someone’s Memory — The Joy of Encountering a Work

The 4K re-release of your debut film Love Letter this April has attracted a lot of attention from younger audiences. It truly embodies the “universality” you aim for as a director.

Iwai: Speaking of music, recently the theme song from The Case of Hana & Alice (2015) went viral on social media in India. It’s called “fish in the pool.” I originally composed it when I was a student. It’s quite moving to see a song I made years ago being used in videos overseas — it really brings a sense of full circle.

Iwai: When we make a film, we put everything into it, striving for our own version of perfection. But once it’s out in the world, any way people interpret or experience it is fine. What truly matters is the fragment of the film that sticks in each viewer’s memory. That fragment might be very different from what I originally intended. That’s the fascinating part. For example, in Love Letter, Miho Nakayama plays two roles, but some people didn’t realize this and watched it thinking it was the same person until the very end. That was intriguing to me. For that viewer, that’s their Love Letter, and that’s perfectly okay.

So even if the way the film is appreciated is unexpected, the important thing is that people have connected with it?

Iwai: Exactly. Even if someone has only seen the trailer or a poster, that’s enough. It’s a gift if the film leaves even a small impression on someone’s memory, because it means you’ve taken up a tiny space in their mind. No one remembers every detail of a film perfectly; the brain simplifies and condenses it. How the audience transforms and holds onto it — in whatever form — that’s what matters. Nowadays, with clips and fragments circulating online, film is inevitably broken down into pieces. For me, it’s fine if people watch on their phones or just save it to a favorites list. The key is that they’ve encountered the work. From there, if it inspires other creators, whether through homage or even copying, if my ideas get passed along like a baton and become part of new creations, that’s wonderful. No matter how fragmented my work becomes, if it remains in someone’s memory, that’s the greatest reward as an artist.

So even leaving a small fragment in someone’s memory brings joy to the work itself.

Iwai: I have plenty of books I’ve bought but haven’t read yet, and I look forward to the moment I finally do. Just having come across them holds meaning. Even if I never read them and eventually discard them, they’ve taken up a bit of my time to consider whether they’re worth it. In the same way, I think my works — my “products”—probably cause more disruptions than I realize in various places. That’s why I truly value the countless small encounters and farewells where a film “exists.”

You mentioned “homage.” NJZ (NewJeans) music videos are filled with tributes to your work. How do you feel about that?

Iwai: I’m really grateful. It’s a true miracle that my older works are still remembered after all these years, and it brings me joy regardless of the form it takes. Recently, Love Letter was re-released in China and surprisingly ranked third on opening day, even alongside new films. In South Korea, a small theater re-screened All About Lily Chou-Chou, which became a long-running success with over 10,000 viewers. It’s incredibly rewarding to see younger generations discovering and appreciating the films.