Kohei Igarashi’s latest film, ‘SUPER HAPPY FOREVER,’ was selected as the first Japanese film to open the ‘Venice Days’ section of the Venice International Film Festival, while Tatsunari Ota’s feature debut, ‘There Is a Stone,’ has been invited to over 10 international film festivals, including the Berlin International Film Festival. One film tells the story of friends reminiscing about a person they once met while visiting a seaside resort. The other is a mysterious adventure of two people who encounter each other by chance at a river and embark on an odd journey involving a stone. Both films, premiering in September, portray miraculous moments shared by people who meet by chance during their travels.

The two directors, both graduates of the Tokyo University of the Arts Graduate School, have collaborated on each other’s projects. “We share what we value when making films,” says Igarashi, highlighting their mutual understanding. Yet, despite their similarities, the charm of their films is strikingly different. As they talk about how these two films came to life, their impressions of each other, and the surprises they found in each other’s works, their approaches to filmmaking and the current state of Japanese cinema gradually come into view.

INDEX

Discussing Films with Neutrality: Tokyo University of the Arts Alumni

You participated as an assistant director in Igarashi-san’s ‘SUPER HAPPY FOREVER.’ To begin with, could you tell us how you two met?

Ota: Originally, we were senior and junior at the graduate school of Tokyo University of the Arts. Just before I enrolled, I saw Igarashi-san’s graduation film ‘Iki wo Koroshite’ (2014) at Eurospace, and my first impression was being blown away, thinking, ‘Wow, someone can make a film like this.'”

Born in 1989 in Miyagi. After winning the Grand Prix at the Kyoto International Student Film Festival with his debut short film ‘Kaigai Shikou,’ he went on to attend the graduate school of Tokyo University of the Arts. His graduation work ‘Bundesliga’ (2017) was selected for Spain’s FILMADRID, among other festivals. His latest film, ‘There Is a Stone,’ is set to be released on September 6, 2024.

Igarashi: I don’t really remember when we first started talking, but I feel like I used to see you often at the smoking area in grad school. Maybe that’s how we started talking?

Ota: I don’t quite remember that [laughs]. The first time I participated on set was for ‘Two of Us’ (2023), the predecessor to ‘SUPER HAPPY FOREVER.’ Igarashi-san asked me if I’d like to join as an assistant director.

Igarashi: I don’t make films in a fully systematized way, where all roles are strictly defined. So it wasn’t really about Ota-kun’s ability as an assistant director, but more that I could talk to him openly about the content of the film and discuss things freely. That’s why I asked him to join me, I think.

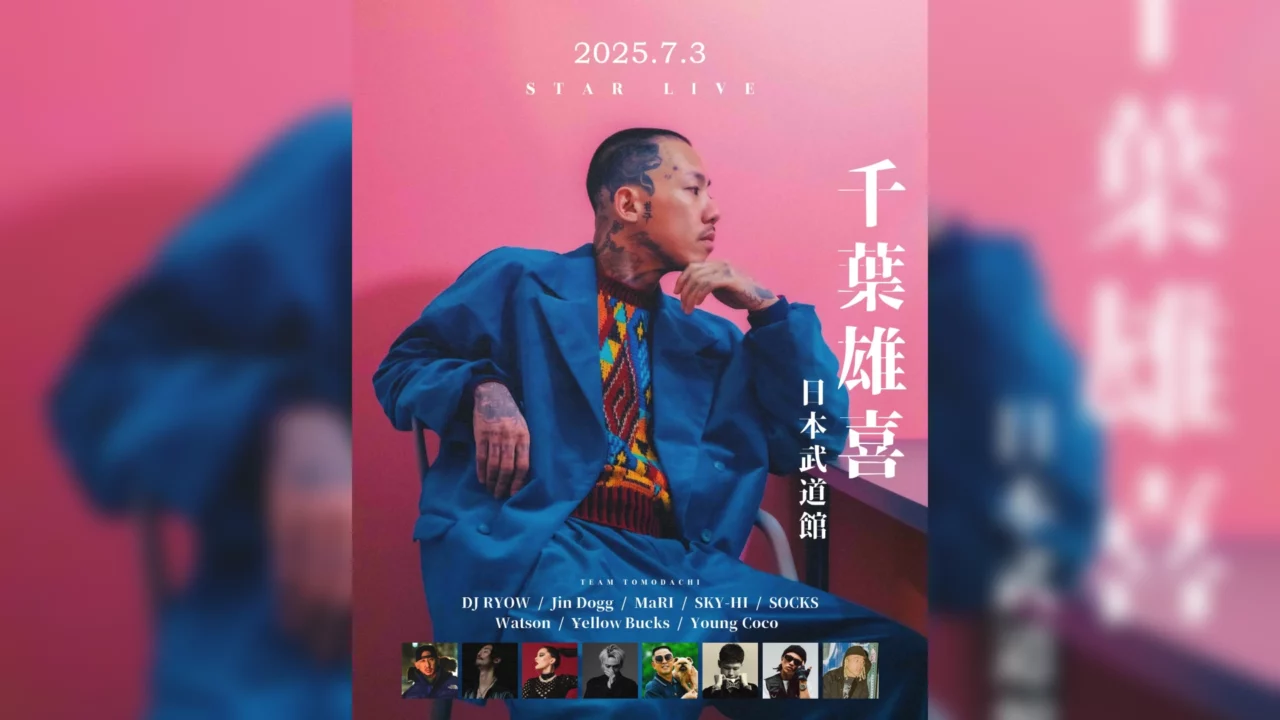

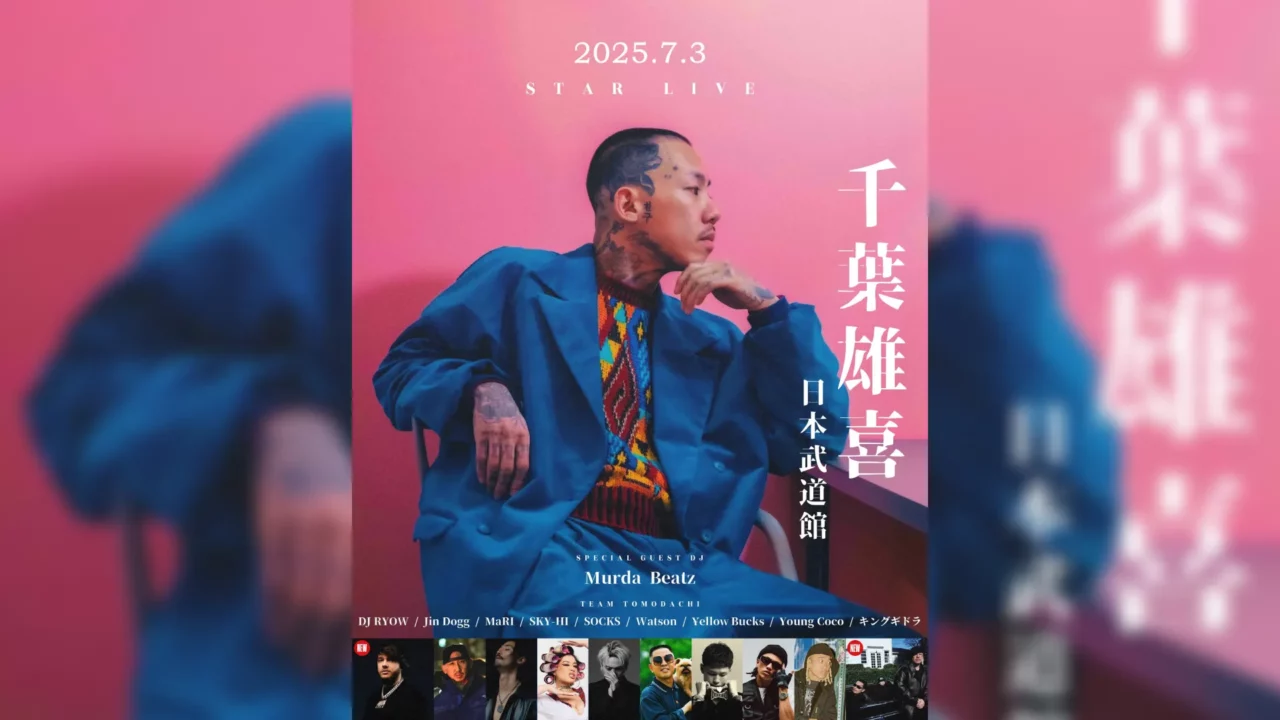

Born in 1983 in Shizuoka. Graduated from the Graduate School of Film and New Media at Tokyo University of the Arts, specializing in directing. His film ‘Iki wo Koroshite’ (2014) was officially selected for the New Directors Competition at the 67th Locarno International Film Festival. The French-Japanese co-production ‘The Night I Swam’ (2017), co-directed with Damien Manivel (known for ‘A Young Poet’ and ‘Isadora’s Children’), was featured at numerous festivals, including the 74th Venice International Film Festival and the 65th San Sebastián International Film Festival. His latest film, ‘SUPER HAPPY FOREVER,’ is scheduled for release on September 27, 2024.

How did you feel after watching each other’s films?

Igarashi: When I saw the completed version of ‘There Is a Stone’ at the 2022 Tokyo Filmex, I was laughing non-stop [laughs]. Especially the scene where Kanou Do crosses the river and meets Ogawa An. The way it transcends imagination was both terrifying and incredibly funny. From there, everything he did—the way he moved, his expressions—was hilarious, and I laughed all the way through to the end.

That was indeed an intense scene [laughs].

Igarashi: It truly is a perfect shot.

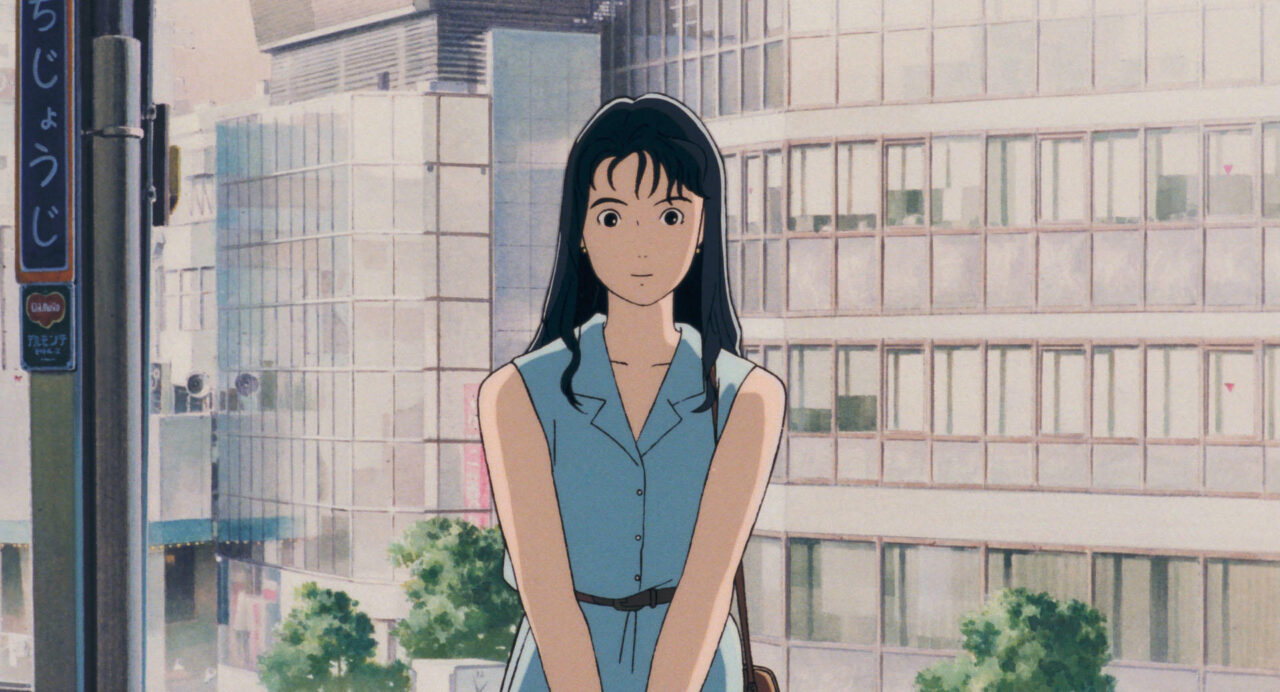

Synopsis: The protagonist, An Ogawa, who works at a travel agency, visits a rural village for research. While walking along the riverbank, having found no tourist attractions and feeling at a loss, she encounters a person (Do Kanou) skipping stones. The two start wandering along the riverbank together, searching for a lost stone.

It’s interesting that both films depict miraculous, serendipitous encounters during travel. Do you find any commonalities between each other’s works, or aspects that you feel are similar to your own personality?

Ota: There is a certain impression that our tastes are similar. When ‘The Night I Swam’ (2017), co-directed by Igarashi-san and Damien Manivel, was released, I was just thinking, “I want to make a film about a boy walking in the snow.” I often feel like Igarashi-san is always one step ahead of me in terms of what I want to do.

Igarashi: But even though they seem similar, in the end, they are completely different. On one hand, I feel we share what’s important when making films, but on the other hand, when I watch the finished films, I realize that they are really quite different from what I would make.

Synopsis: On August 19, 2023, childhood friends Sano (Hiroki Sano) and Miyata (Yoshinori Miyata) arrive at a resort hotel in Izu. As they visit various locations around the hotel and the seaside, they begin searching for a lost red hat from the past. This is the place where Sano first met his late wife, Nagi (Nairu Yamamoto), and fell in love with her five years ago.

Ota: Certainly. Even in depicting a chance encounter, I tend to prefer a more direct approach, while Igarashi-san leans more towards fiction. We both value the same things, but the “trees” we lean on are different. The starting point is the same, but the difference lies in whether we push more towards the realm of film or try to contain it within something more pre-filmic.

Both films are also about searching for lost things. In SUPER HAPPY FOREVER, they are continually searching for a lost hat, while in There Is a Stone, they are looking for a stone lost in the river.

Igarashi: I recently realized, after being told by someone, that I seem to always be searching for something. In ‘Iki wo Koroshite,’ it’s a dog they are looking for; in ‘The Night I Swam,’ they are searching for the father’s workplace; and now, it’s a red hat.

Is the theme of “searching” something that’s easier for you to work with?

Igarashi: I don’t consciously realize it, but I think I’m probably interested in what is visible and what is not. In film, we only see what is on the screen, but in reality, everyone imagines and enjoys what exists beyond the frame. I guess I’m interested in how to perceive both what is shown and what is not.

Ota: Rather than thinking of it as a story about “searching,” I simply translated my experience of picking up stones with friends into a narrative. When we were picking up stones, a friend lost a stone by the river, and even though we went looking for it, we never found it. That experience was really fascinating to me.

Igarashi: To follow up on what we discussed earlier, ‘There Is a Stone’ is a film that’s very much about “what is shown.” It’s like “there is a stone” [laughs].

INDEX

How Film Reveals Character: A Look at the Two Directors Through Their Films

How do you each perceive the other after working together on films?

Ota: What I liked most on set was that Igarashi-san really eats well and sleeps well.

Igarashi: [laughs].

Ota: During filming, he’s always the first to go to sleep among the staff and cast. I often find myself staying up late, worrying about the next day’s shoot, but Igarashi-san would eat and then immediately go to bed, saying, “You won’t know until you see the set.” In the morning, he would wake up early, sit cross-legged on a wooden terrace with a view of the sea, and read the script. It looked so comfortable and made me realize, “Oh, this is the way to do it.” It was quite a revelation.

Igarashi: During filming, I find myself completely worn out. Although I prepare detailed plans, I don’t adhere to them strictly. Instead, I adapt to each situation as it arises, which leaves me exhausted by the end of the day. At that point, I can’t think clearly, so I prefer to go to bed early and rise early, using the morning walk to sort through my thoughts.

Ota: Realizing that you can’t think straight when you’re exhausted is a lesson that applies not only to filmmaking but to everything.

-Igarashi: Do you think that your way of being came out in the film?

Ota: I think that aspect of Igarashi-san definitely comes through in his work. He doesn’t push himself to make things work; good ideas naturally emerge on set. That kind of coolness is likely reflected in his films.

Igarashi: From my perspective, when I ask Ota-kun, “What do you think about this?” he usually starts with a long “Hmm…” and doesn’t answer right away [laughs]. He seems to have no preconceived notions about anything. So he takes his time to think things through for each situation. When he eventually says, “I think it might be like this,” he sticks firmly to that idea. Ota-kun has a combination of sincerity and stubbornness.

I think ‘There Is a Stone’ is a perfect example of that. As someone who makes films, I often wonder how you make a story about “two people meeting and walking by the river” work. But Ota-kun doesn’t have any preconceived notions about what a film should be or what kind of story needs to be told. His straightforward approach is really impressive.

INDEX

Embracing the Present: Integrating Non-Fictional Space into Fiction

Do you usually discuss specifics about filmmaking, like how to write a script or find locations?

Igarashi: I don’t think we’ve ever had such discussions. We usually just talk about what we see as we walk around, saying things like, “This scene is interesting” or “That place looks good.” Sometimes, we comment on the vibe of store clerks we encounter during location scouting.

Ota: It’s more about coming to a mutual understanding of specific locations rather than discussing how to make a film.

How did you find the river in ‘There Is a Stone’?

Ota: When we were searching for shooting locations, we chose the river that seemed the most walkable. During the shoot, we actually walked along the river, planning our path day by day—“Today we’ve reached this point, so tomorrow let’s walk from here to there.” We filmed exactly where we walked, so you could say the plot itself was born from that location.

The setting of ‘SUPER HAPPY FOREVER’ is described as “a certain resort area in Izu,” but it was actually filmed in various locations in Izu and Atami, correct?

Igarashi: Yes. I can’t finalize the plot or script until the locations are decided, so once we settle on a place, I start developing specific scenes and adjusting them to fit the actual location. That’s how I approach writing the script.

Ota: If you try to force a shooting location to fit the story, it can increase the level of fiction and make the filming process more complicated.

Igarashi: It’s not just inconvenient; it stifles creativity. For example, if you want to show a corridor and a room as part of the same hotel but they are actually in separate locations, you need to carefully calculate the background scenery and angles. Instead of spending time on that, I prefer to think creatively and capture what’s possible.

Of course, even in the same location, you need to be resourceful to make things work. It’s enjoyable to discuss these aspects with Ota-kun because we share a common approach to space. We can quickly agree on, “This is how we should shoot this.”

Ota: Fundamentally, we both share a mindset of trusting what’s there. Whether it’s a location or people, we prefer to work with what’s available and believe in it.

Ota: Given the previous discussion, I think ‘SUPER HAPPY FOREVER’ is a film with a lavish background. It features not only the actors but also the people who happened to be there, and the sea and cityscapes are clearly depicted.

By the way, I noticed that on set, Igarashi prioritized what appeared in the background, like trying to capture a boy running in the distance. This time, it seems like even more uncontrolled elements from the background were included. Was this a deliberate choice?

Igarashi: In feature films, even if the story’s setting is fictional, what appears on the screen is reality. This reality inevitably seeps into the fiction. Sometimes, when reality overshadows too much, it can create significant gaps in what should be a cohesive fiction. But I actually prefer it when there are many gaps. I believe those gaps are where something emerges between reality and fiction. For this film, perhaps the gaps were created by the sea, streets, and people of Izu and Atami.