Have you experienced the 120th Anniversary of Émile Gallé’s Passing: Émile Gallé: Longing for Paris exhibition at the Suntory Museum of Art yet? Widely regarded as one of the most renowned glass artists in the world, Émile Gallé was also a visionary in ceramics and furniture design, shaping a unique artistic universe. Through 110 captivating works and materials, this exhibition invites you to trace the creative journey of an artist who left an indelible mark on his era. With the exhibition now halfway through its run, here’s an insider’s guide to the highlights you won’t want to miss.

INDEX

From Hometown Nancy to the Vibrant City of Paris

Émile Gallé was a 19th-century French artist known as one of the leading figures of Art Nouveau. He achieved international success, particularly in the field of glass art, leaving behind many works featuring organic designs inspired by flora and fauna. Many people may have a vague image of him as “the artist behind the wavy, floral vases.

Gallé was born in the regional city of Nancy, located near the border between France and Germany, and he remained based there throughout his life. The production of his works also took place in Nancy. As both an accomplished artist and a businessman, Gallé was a prominent figure in Nancy. However, the capital city of Paris is an essential element in the story of the artist Émile Gallé. He should be viewed not just as “an artist from Nancy,” but rather as “an artist with two homelands: his hometown of Nancy and the capital, Paris.” For reference, the distance between Nancy and Paris is approximately 300 km, roughly the same as the distance between Tokyo and Nagoya in Japan.

This exhibition focuses on the relationship between Gallé and Paris. There are two key points to consider. One is how Gallé stepped up through his participation in the Paris Expo. The other is how Gallé, based in the regional city of Nancy, worked to succeed in Paris. The exhibition is structured in three main chapters, with the former addressed in the main sections and the latter explored through “columns” interspersed between the chapters.

Gallé participated in the Paris Expo about every 11 years, first as an assistant to his father, and later as the central figure in three of them. The Expo were grand international events, showcasing Gallé’s finest works at each stage of his career. So, what kind of works did Gallé present at each of these expos? Let’s take a look at some of the featured pieces.

INDEX

A Young Gallé: Observing the 1867 Expo Behind His Father’s Back

In his 20s, Gallé participated in the Expo with the help of his father, presenting the goblet Portrait of Jacques Callot. The piece features a transparent glass base decorated using “engraving,” a popular technique of the time, and is finished with gold accents. The shape of the goblet follows the traditional design, and Gallé’s personal style is still in the background at this point. Interestingly, the man playing the instrument at the center of the design is based on an engraving by Callot, a copperplate artist from Gallé’s hometown of Nancy. This marks an early expression of Gallé’s love for his hometown. At the same Expo, Gallé’s father received an honorable mention in the categories of crystal glass, luxury glass, and stained glass.

INDEX

Gallé in his 30s: His First Expo (1878)

Eleven years later, at the Paris Expo the year after Gallé took over the family business and became a manager, he presented works like this one. The footed cup The Four Seasons is a small piece, about the size of a child’s tea bowl, but it captivates with its delicate decorations. The names of the zodiac signs are inscribed along the rim, and upon closer inspection, the constellations are engraved beneath them. The front depicts Taurus, with a star symbol in between, and to the right is Gemini… and so on. The engravings on the sides feature female figures inspired by the four seasons.

At this exhibition, several original pieces displayed at past Paris Expos, including this one, are showcased. These are not “identical models,” but rather the actual works that have witnessed history. Knowing this adds a deep sense of nostalgia, as it feels as if the piece holds the sighs and admiration of the spectators from that time.

That said, by this point, Gallé’s works hadn’t undergone significant changes in technique. What was most innovative for Gallé at the 1878 expo was not the decoration, but the base material of the glass itself.

Let’s take a look at the vase Koi with a design of koi fish from Hokusai Manga (a time when Japonism was at its peak!). The undulating shape of the vase refracts the light, creating the illusion of koi swimming in water. This truly makes you realize that working with glass means designing the transmission and refraction of light.

If you focus on the glass portion, you’ll notice a faint bluish tint in the glass. This is the new material Gallé introduced at the 1878 Expo, called “moonlight-colored glass.” Moonlight-colored glass became so popular that it was imitated across Europe. At that expo, Gallé won the bronze medal in the glass category.

Additionally, don’t miss the panel displays that clearly explain the decorative techniques. The variety of decoration styles showcases the continuous dedication and refinement of the artists and craftsmen. Some of these techniques, such as “patiné” and “marquetry,” were later developed by Gallé himself, so be sure to glance through them as a helpful hint for your viewing experience.

INDEX

The 1889 Expo: Gallé’s Second Major Showcase

Another 11 years later, Gallé’s second participation in the 1889 Paris Expo was, in short, a great success. Among the approximately 300 glass works Gallé presented, the standout was his use of “black glass.” In line with the grand stage of the expo, Gallé introduced works utilizing black glass, a material that had rarely been used before. (One might even imagine naming it something like “Glass of the Night,” similar to how he named his “moonlight-colored glass.”) The black color was used to express themes of life and death, sorrow, and it added an emotional depth to the pieces. From this point onward, Gallé’s works clearly began to develop a stronger narrative quality and became more emotional in nature.

In the large vase Joan of Arc, created using black glass, Gallé employed both raised (relief) and recessed (intaglio) engraving techniques. When light is cast on the piece, only Joan of Arc appears to shine, resembling a single beam of light piercing through the battlefield.

Gallé is said to have referred to his black glass works as “vases of sorrow.” This sentiment becomes particularly clear when looking at the vase Dragonfly. The dragonfly, exhausted, falls toward the water’s surface. If you look closely at the lower part of the piece, you’ll notice that its reflection on the water is also delicately expressed through subtle raised and recessed details. The dragonfly is heading toward death while gazing at its own approaching reflection. Standing before it, you can’t help but feel an intense emotional connection, as the piece pulls you in with its strong gravitational force. By the way, the dragonfly was a favorite motif of Gallé, who had a love for insects, and you can find many dragonflies throughout this exhibition. At this expo, where Gallé’s artistic identity truly blossomed, he achieved great success, winning the Grand Prix in the glass category, as well as a gold medal in the ceramics category and a silver medal in the furniture category.

INDEX

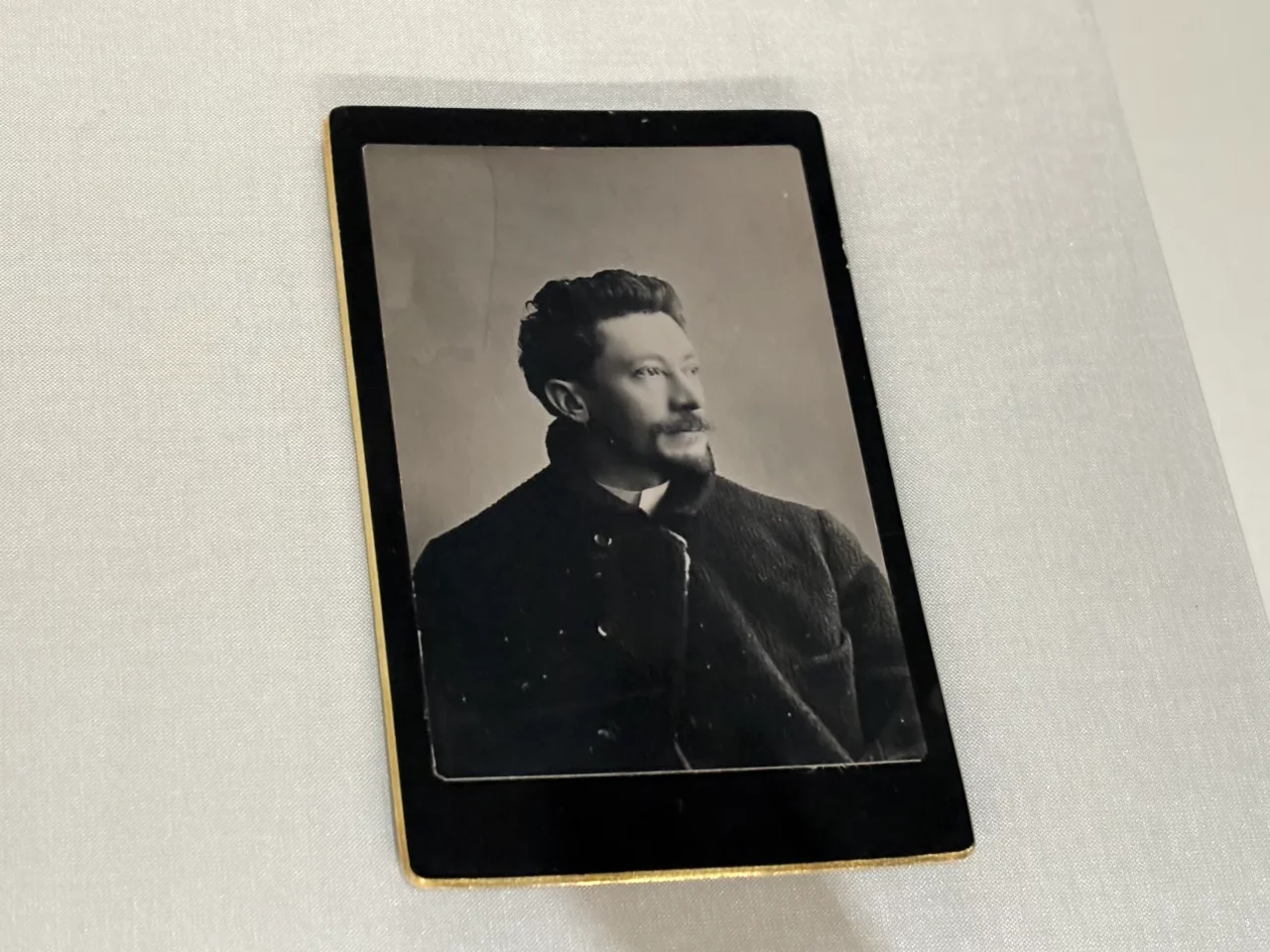

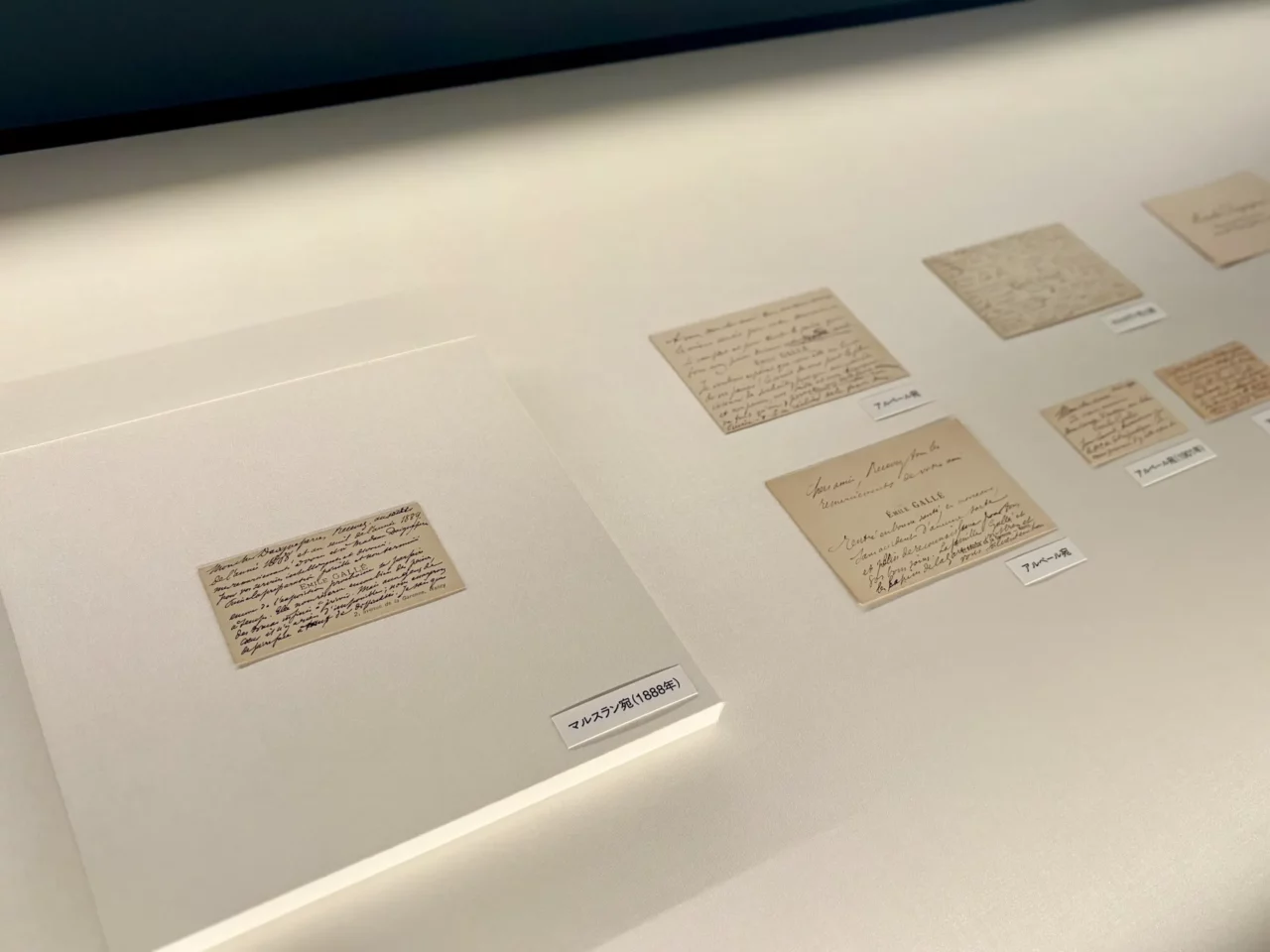

Handwritten Notes: A Reflection of Personality

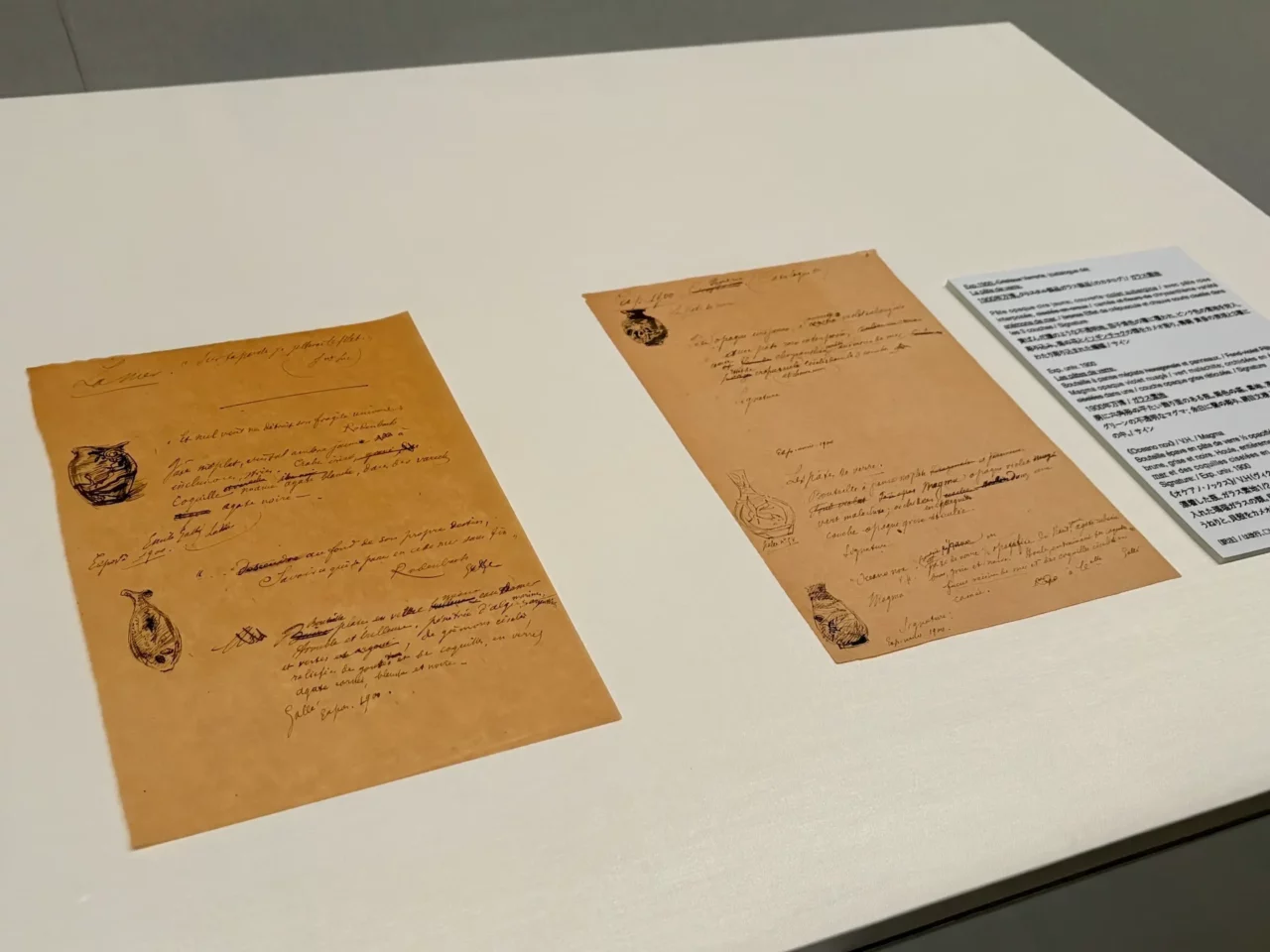

One of the must-see items in this exhibition is Gallé’s handwritten message card, displayed in Column 1. This piece is part of the “Degpeers Family Collection,” which was recently acquired by the Suntory Museum, and it is being shown for the first time in this exhibition. The Degpeers family, based in Nancy, were key partners in Gallé’s business, managing the sales of his works in Paris and playing a significant role in supporting his popularity there. The card features elegant handwriting, expressing Gallé’s thoughts and feelings as the expo approached.

First and foremost, they are small! The cards are all business card-sized… but, interestingly, the messages are written in the margins of the cards themselves. From the tiny letters carefully written on the small paper, you can almost imagine Gallé’s personality, which feels amusing. Some of the cards include Japanese translations, and the content is surprisingly humble. Phrases like, “I am very afraid of not being able to measure up to such a big task,” or “Let’s meet again on the stage of honor!” convey the pressure and excitement Gallé must have felt as the expo approached. It’s a moment that makes Gallé feel incredibly relatable and easy to empathize with.

On the other hand, here is a handwritten note by Gallé regarding his creative process (displayed in Chapter 3). The illustrations are smaller than expected, and there is a considerable amount of text. These kinds of sketchbook-like notes are fascinating as they provide a glimpse into the artist’s thought process. Additionally, you can also see records of orders for his works from the expo, so be sure to pay attention to the paper materials displayed in the exhibition room.

INDEX

The Voice of ‘Speaking Glass’

In another column section, the connection between Gallé and Parisian high society, which blossomed based on his success at the expo, is highlighted. The meeting with Count Montesquieu, who played a crucial role in his networking, is also noteworthy. However, the work that stands out is the vase “Pelican and Dragon,” made using black glass.

The motif is carved in white and black, contrasting light and darkness, good and evil. However, upon walking around the piece, one notices that the dragon is actually much larger than the pelican. The dark wings of the dragon spread out, enveloping the vessel, suggesting that evil’s power is overwhelming, while good seems to be the minority. Interestingly, Gallé dedicated a version of this work to William O’Brien and his wife, who were leaders of the Irish nationalist movement. This is something I learned for the first time at this exhibition, and it reveals that Gallé had a highly social and humanitarian side.

In 1894, between the Expos, the “Dreyfus Affair” occurred, a significant event in 19th-century France that divided public opinion. It might be difficult for us in modern-day Japan to imagine, but the case involved a Jewish officer who was imprisoned on charges of being a German spy. The controversy over whether he was guilty or innocent led many French citizens to publicly voice their opinions and engage in debates (the case was later concluded as a wrongful conviction in 1906). Gallé, from an early stage, supported Dreyfus, taking the stance that it was a wrongful conviction orchestrated by the military.

At the 1900 Paris Expo, Gallé expressed his stance more openly, creating several related works and using bold displays to make his position known. While his stance was well-received in Paris, it earned him strong opposition in his hometown of Nancy. Despite being a prominent artist of the region, Gallé reportedly found that no one would even greet him in public in Nancy. Ironically, in the same year as the Dreyfus Affair, 1894, Gallé had opened a one-stop manufacturing factory for his company in Nancy, solidifying his presence locally. His commitment to his beliefs and sense of justice was admirable, but it is easy to imagine that it must have been an incredibly difficult situation for him.

The chalice “Fig” displayed in Chapter 3 seems to embody Gallé’s humanitarian sentiments. A chalice is used in the Christian sacrament to drink the wine, which symbolizes the blood of Christ, sacrificed for the people. On the bottom of this chalice, a verse from Victor Hugo is engraved: “For all men are the sons of the same father. They are the tears that have fallen from the same eyes.” Two droplets, resembling tears, flow down the surface of the chalice. One of them is stained red, resembling blood. While both droplets fall from the same eyes, only one appears to bleed. Given the various symbolic meanings of figs in Christianity, it is impossible to definitively interpret the artist’s intent. However, the piece seems to ask: why must someone be sacrificed or why is only one harmed? This question seems to be voiced with sorrow and indignation. Gallé referred to his works, which incorporate verses and literary excerpts to resonate with meaning, as “speaking glass.”

INDEX

Gallé in His 50s: The 3rd Expo (1900)

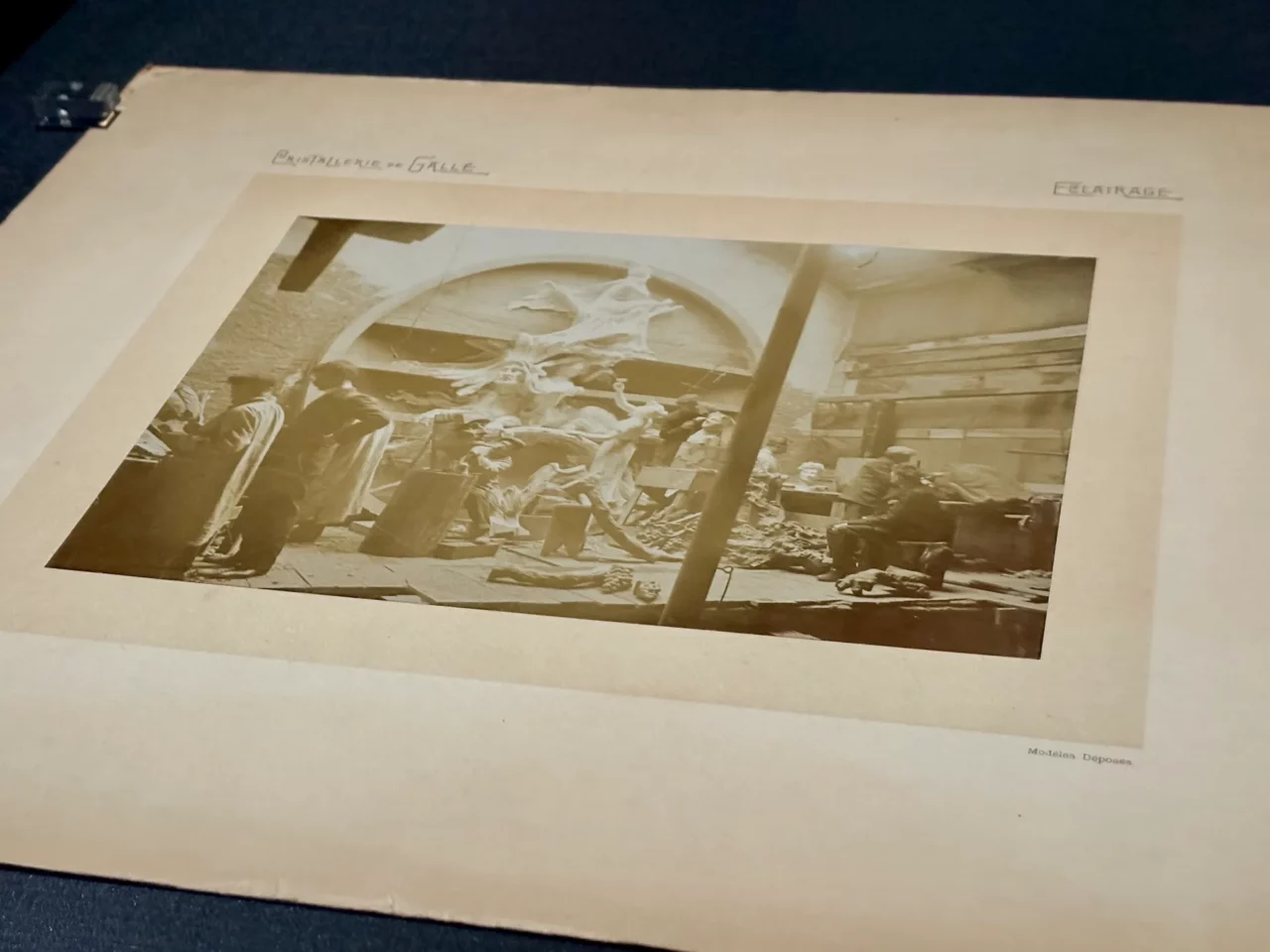

Eleven years after the great success of the previous expo, in 1900, Gallé’s art entered its mature phase and was more dynamic than ever at the largest “Exposition Universelle” in history.

Looking at the morning glory-shaped vase “Moth,” instead of adorning the vase with floral decorations, the vase itself has transformed into a flower. The delicate veins running through the petals are intricately expressed, making it truly a glass flower. While it could still be used functionally, rather than arranging flowers in it, you would prefer to admire the vase itself. Through research into materials and techniques, the range of expression has expanded dramatically, and the piece has evolved from a “beautifully decorated vessel” into an “artistic glass object with intentional expression.”

The use of the technique “fusion,” which involves attaching separate glass parts, results in fascinating three-dimensional works. In the foreground, there is a piece inspired by grapes, and in the background, one inspired by tadpoles. Each piece is engraved with a line of poetry that reinforces its theme. If you compare these with the goblet from his first expo 30 years ago, you can truly appreciate the freedom of thought based on natural observation, the technical skill to realize it, and the spiritual depth that speaks to the viewer. I felt that I could finally understand why Émile Gallé became so famous in the field of glass.

The pieces displayed at the 1900 expo are full of captivating works that make you wonder, “How is this possible?” and there are so many that it’s hard to know where to begin. I would recommend taking plenty of time to explore Chapter 3 during your visit.

By the way, in this chapter, you can also see Gallé’s furniture works. The chest in the foreground is called “Forest.” Through the framework resembling tree branches, a natural landscape depicted with marquetry unfolds, creating an immersive experience. If you’re a fan of Art Nouveau, you’re sure to be mesmerized. Notably, at this year’s expo, Gallé won both the Grand Prix in the glass category and the Grand Prix in the furniture category.

INDEX

Final Years: Reflecting on Life and Death

Starting around the year after the 1900 Expo, it is said that Gallé began to repeatedly undergo treatment. In the final exhibition room, with the lights dimmed, Gallé’s works from his final years emerge under the spotlight. As you view them, try to quietly engage with the works, aligning yourself with Gallé’s heart as he continued to create in the face of death, possibly fully aware of it.

One of Gallé’s famous works, the mushroom lamp, is inspired by the “Hyotake” (One-Night Mushroom). This mysterious mushroom dissolves and disappears from the edge of its cap after it matures, due to its own enzymes. The liquefaction and disappearance are believed to be for the purpose of dispersing spores, thus ensuring the next generation. Perhaps Gallé felt a connection to the cycle of life, including his own, in this phenomenon.

The final work you will encounter in this exhibition is, once again, the dragonfly. Created between 1903 and 1904, it was made in the year Gallé passed away from leukemia, or possibly the year before. Through a combination of complex techniques, the dragonfly appears to be desperately fluttering its wings. One could interpret this as a reflection of Gallé himself, struggling to continue creating until the very end of his life. On the other hand, the milky-white cup resembles an eggshell, evoking a sense of something new and larger being born, giving the piece a mysterious brightness.

Gallé passed away in 1904 at the age of 58. In his final years, he was dedicated to the formation of the Industrial Arts Alliance in his hometown of Nancy. Knowing this, in light of the history of his relationship with his hometown that we’ve seen in this exhibition, it evokes a feeling of sadness.