In March of this year, Berlin Techno was officially registered as part of Germany’s Intangible Cultural Heritage by UNESCO.

‘More than just a music genre, techno represents a living culture, standing in contrast to the traditional experience of classical music and other forms,’ (UNESCO official website).

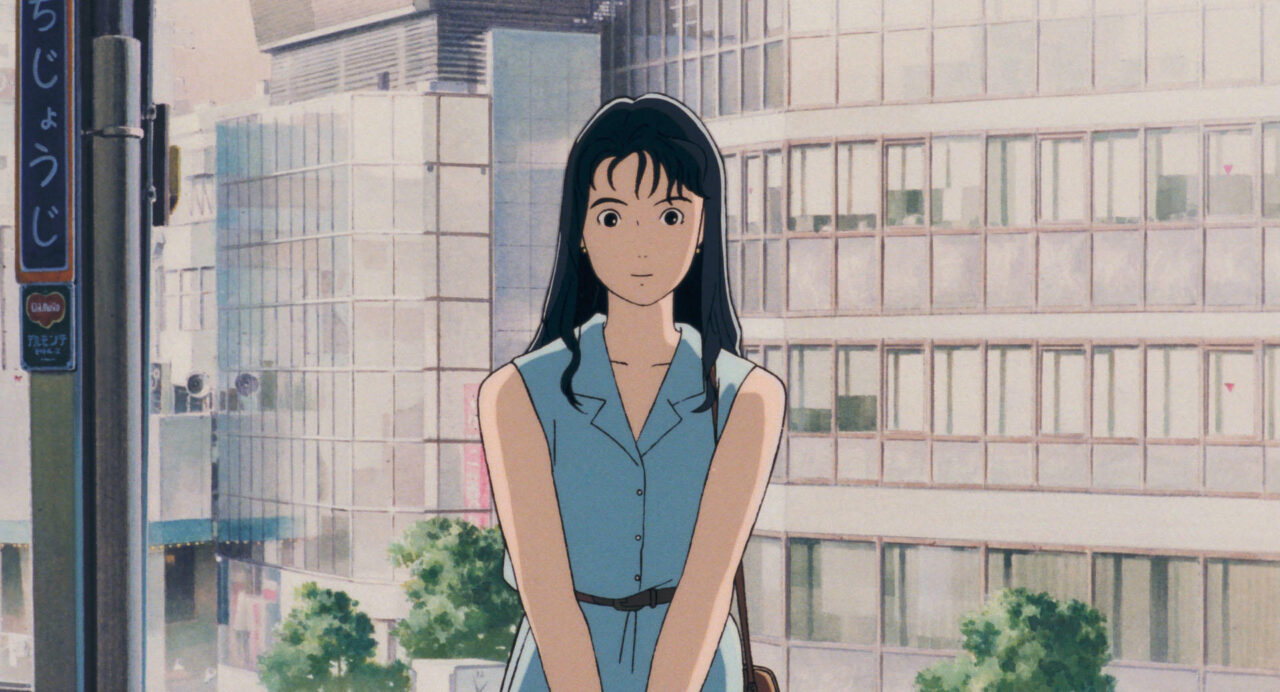

‘Techno, which was still niche in Berlin in the late 1980s, became the focal point of the club scene that shifted eastward with the fall of the Wall. Berlin Techno is a fusion of Detroit’s techno roots with Berlin’s unique electronic music tradition, sparking imagination and inspiring creativity in music, art, and fashion,’ (Mark Reeder).

In 2016, the world-renowned club Berghain was recognized as a cultural monument by the German government. But what led Berlin’s techno culture to become a global influence on the club scene and gain permanent protection under the law?

We spoke with Mark Reeder, a key figure and music producer who has been deeply involved in the scene since the early days of Berlin Techno, to discuss the evolution from its origins to the current scene. We also highlighted the newly opened open-air club, Turbulence, which has been making waves since its launch last September, to get his take on the latest developments in Berlin’s club scene.

INDEX

Mark Reeder: A Music Producer at the Heart of Berlin’s Club Culture Evolution

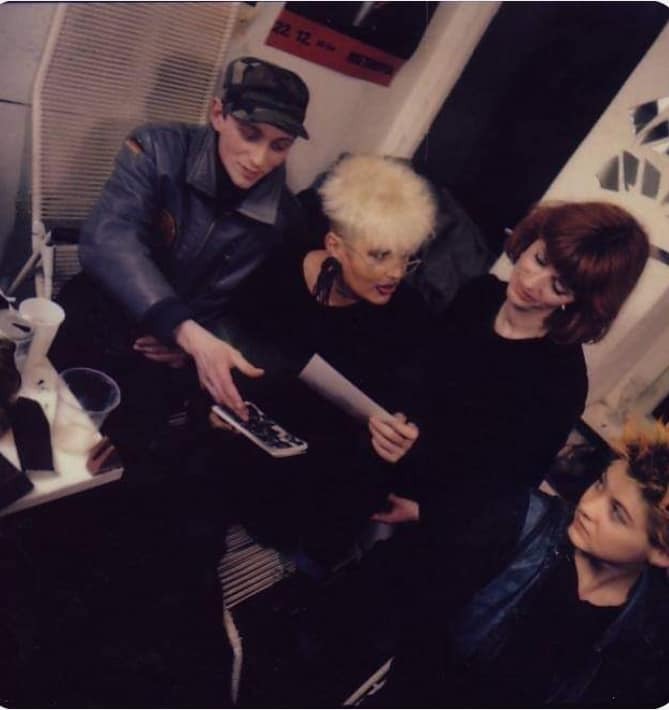

Mark Reeder has lived in West Berlin since 1978, where he has been active as a musician while releasing tracks by Paul van Dyk, Mike van Dyk, and Takkyu Ishino through his label MFS. He has also remixed tracks for Depeche Mode and New Order. In 2015, a documentary film about his life, ‘B-Movie: Lust & Sound in West Berlin,’ was released and is still being shown at Berlin’s Sputnik Kino. In Japan, a screening event was held last year at DOMMUNE. What has Mark witnessed in Berlin’s club culture over more than 45 years?

You were one of the key figures deeply involved in the early days of Berlin Techno. Could you tell us about the atmosphere in Berlin at that time?

Mark : In the 1970s, Berlin was in the era of Krautrock, with pioneers of electronic music like Klaus Schulze, Tangerine Dream, and Manuel Göttsching being active. However, back then, the city wasn’t yet known as a music hub. There’s no doubt that the fall of the Berlin Wall in November 1989 was the most significant political event that dramatically changed the city’s music scene. The center of the club scene shifted eastward, techno became established, and it ignited the imagination of people yearning for freedom, stimulating creativity in music, art, and fashion.

In particular, the techno rave ‘Love Parade,’ which started in the same year as the fall of the Wall, has had a profound impact on Berlin’s current club scene. I participated from the very first event, and the revived ‘Love Parade’ became a positive action, replacing demonstrations with placards and flags, political speeches with techno and house music, and spreading messages of love and peace. It was a moment when everyone could finally look toward the future with positivity, free from the oppressive shackles of the Cold War. I believe that the ‘Love Parade’ sent a positive message not only to Berlin but to the entire world. It was an unprecedented event where many people enjoyed themselves, danced in the streets, and everything was free of charge, leaving a significant impact.

How did you personally get involved in the club scene and build your career?

Mark:

One of the most significant turning points in my over 45-year career was probably the ‘Konzert zur Einheit der Nation’ held at SO36 on June 17, 1981. At that time, our band didn’t have a name, but after a local magazine referred to us as ‘two unknown Brits’ in a live review, we became known in the new wave avant-garde scene as ‘Die Unbekannten’ (The Unknown). This concert led to us releasing our first vinyl through Monogam Records, the same label that released albums by Einstürzende Neubauten and others.

In addition to the first ‘Love Parade’ in 1989, I also performed at the legendary festival ‘Geniale Dilettanten’ in 1981 and at the inaugural experimental music event ‘Berlin Atonal’ in 1982. These experiences were also very important in my music career.

At the same time, I was the sound engineer for bands like Malaria! and Die Toten Hosen, which led to an offer to produce an album in East Berlin in 1989. Following the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1990, I founded the electronic music label MFS, specializing in electronic music.

The music scene in West Berlin during the 1980s was quite avant-garde, significantly different from that in East Berlin. You have deep connections with key figures who have influenced the current Berlin club scene. Would you say that Monika Döring, the founder of ‘The LOFT,’ who unfortunately passed away in May, was one of them?

Mark: I worked for many years at ‘The LOFT’ as a bouncer, sound technician, and occasionally as a translator, and Monika was like a mother to the Berlin music scene. She always looked out for us and took care of us, and she was always open-minded and accepting of avant-garde music. She started ‘The LOFT’ to give local bands a chance. Not only did ‘The LOFT’ incorporate 1980s music, but it also embraced techno and experimental avant-garde music. With a capacity of 800 people and a high-quality sound system, ‘The LOFT’ established itself as the largest gay club in Europe during the 1980s and held a solid position in West Berlin.

What do you think about Berlin Techno being registered as a UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage? Also, why do you think it has reached this level of recognition?

Mark : I think it’s extremely important. I am also one of the people who wrote a paper supporting the significance of its UNESCO recognition. This topic is very dear to me, and I believe it is essential for the development of Berlin’s electronic music culture. No one would deny that techno originated in Detroit. However, it was in Berlin that the true scene was born. Therefore, the recognition of Berlin Techno should be shared not only with Berlin but also with Detroit.

However, without the fall of the Berlin Wall and the ‘Love Parade,’ it would not have become the global phenomenon it is today. In the late 1980s, techno was still a niche genre, with only a few records made by a small group of Detroit artists. They were influenced by German electronic music and wanted to add a dance groove to it. This feeling was similar to what I experienced with trance, where I wanted to mix the hypnotic trance-inducing sequencers of Tangerine Dream and Klaus Schulze with emotional melodies like those of Wagner or Mahler, and add the groove of techno to it.

What do you think about the ever-evolving club scene in Berlin?

Mark: Berlin has talented young artists like Grossstadtkind, Linus Frisch, and Berlin Banter, who are contributing to the city’s vibrant music scene. They are carrying forward the legacy of creativity and innovation in Berlin’s electronic music and paving the way for new musical directions in the future.