Nearly three years after 2022’s “Betsu No Jikan,” Takuro Okada returns with “konoma,” a new original studio album that quietly yet decisively opens another chapter in his evolving practice. Jointly released by Los Angeles–based labels Temporal Drift and ISC Hi-Fi Selects, the record feels less like a statement of arrival than an invitation to step into a space where time, place, and influence overlap.

Deepening the intricate interplay of improvisation and meticulous editing that marked his previous work, “konoma” unfolds with a newfound openness. Its sounds are gentler on the surface, but beneath that ease lies a densely layered world that resists easy categorization. This is not a turn toward pop so much as a widening of perspective, one that rewards careful, curious listening.

The album takes its name from a phrase in Okakura Tenshin’s The Book of Tea: konoma, “between the trees.” In that in-between space, Okada reflects on what it means to make music as a Japanese artist in the present moment, assembling fragments of memory, history, and sound into a fluid bricolage of identity.

Echoes of Ethiopian music, jazz stretching from Japan to Europe and the United States, blues, ambient, and beat-driven forms drift through the record. Rather than colliding, they trace imagined lines of connection—paths that might once have existed, or perhaps still do.

In this conversation, Okada speaks candidly about the ideas that shaped “konoma”: his self-questioning approach to engaging with Black music, the impact of time spent abroad, and the inspiration he found in contemporary artist Theaster Gates’s concept of “Afro-Mingei.”

INDEX

Wanting the Groove to Never End

When did the initial ideas for this album begin to take shape?

Okada: When was it exactly… After releasing “Betsu No Jikan,” I was constantly on the move, working on production and support projects. In the midst of all that, maya ongaku invited me to play a show at WWW (*). Around that time, I had this vague image in mind: music built on a Willie Dixon–like bass line, repeating in a minimalist way, while remaining harmonically and melodically free—something that sits right on the edge, just barely avoiding turning into a jam. To share that mental image with the band, I started using the phrase “ambient blues.” I think that became one of the key starting points for the album.

※Editor’s note: Referring to rhythm echo noise, a joint event by maya ongaku and Shibuya WWW held on August 10, 2023.

I was actually at that show as well. It felt improvisational, but at the same time it clearly wasn’t bound by the conventions of a 12-bar blues. More like an ambient-tinged take on Americana—really fascinating. For you, is blues still one of your core roots?

Okada: Definitely. When I was in middle school, I was completely immersed in blues. I was listening to records nonstop, and I’d also go sit in at jam sessions at local blues clubs back home.

Born in 1991 and raised in Fussa, Tokyo, Takuro Okada is a guitarist, songwriter, and producer. He began his career in 2012 as a member of the band “Mori wa Ikiteiru,” and, following the group’s disbandment, moved fully into his solo work.

His solo albums include “Nostalgia” (2017), “MORNING SUN” (2020), and “Betsu No Jikan” (2022), the latter featuring contributions from Sam Gendel, Carlos Niño, and Haruomi Hosono. Beyond his own releases, Okada has been an in-demand guitarist, taking part in recordings and live performances with artists such as Yuuga, Satoko Shibata, ROTH BART BARON, and never young beach.

Still, since becoming a professional, you haven’t really made anything that could be described as “straight blues,” have you?

Okada: At some level, I always feel the urge to play blues. But the deeper you go, the more you realize how tightly it’s bound to the cultural and historical realities of African American life at that time. Knowing that, I can’t help but hesitate. I’m living in a completely different era, in a completely different environment, and to simply trace the form of blues from that distance never feels quite right to me. That hesitation has been there all along.

When I reach that point, I start thinking about whether the mood and minimalism embedded in blues might be approached differently—by connecting them to the kind of minimal, improvisational playing I explored on “Betsu No Jikan,” filtered through ideas from modal jazz and ambient music.

That comes through. That performance, in particular, seemed to unfold through the repetition of very minimal phrases.

Okada: I’ve said this before in other contexts, but I’ve always had this desire — like wishing the opening of Miles Davis’s “So What” could just continue forever, or wanting to hear Magic Sam’s one-chord boogie go on endlessly. When I tried to translate that feeling into my own music, that’s where I ended up.

Thinking back, what drew me so strongly to blues records in the first place was that sense of atmosphere. The huge reverb on Chess Records releases, or the eerie, almost spectral sound of country blues — those are qualities unique to recorded sound, something quite different from live performance. That sonic world really captivated me.

On this album as well, tracks like “November Owens Valley” seem to embody that idea of “ambient blues.”

Okada: Yes, absolutely. Talking about it now, I’m also reminded of a conversation I once had with Yakenohara at a gathering, which left a strong impression on me. He said that when he’s making beats, he’s always aware of borrowing from other cultures, but when he’s working on ambient music, that sense of borrowing somehow falls away. I found that incredibly relatable.

Maybe that sense of release is part of why I was drawn to thinking about blues and ambient music together.

Why do you think ambient music creates that feeling? It’s also a fairly intellectual concept, closely tied to the frameworks of contemporary music. Could something like a “non-folk” quality be at play?

Okada: That could certainly be part of it, though there are probably several factors involved. One explanation might be its musical flexibility. The simple scales often used in ambient music, its reliance on repetition, its non-beat fluctuations, and its unadorned melodies and harmonies—those elements can be found, in different forms, in indigenous and vernacular music around the world. That openness is probably what allows ambient music to connect so easily with so many different traditions.

At the same time, even before Brian Eno articulated the concept of ambient music, there was already plenty of music that carried an ambient-like mood—not just in contemporary music, but across many cultures, where it existed naturally, woven into everyday life.

INDEX

Minimalism Informed by Ras G and Madlib

At the same time, tracks like “Galaxy” lean more toward beat music—almost like sharp-edged instrumental hip-hop—and bring in colors that feel different from the ambient side of the album. Where did those elements come from?

Okada: In a very simple sense, I just fell completely in love with that kind of music. I was listening intensely to people like Ras G and Madlib. That’s actually why I reached out to Yakenohara—I really wanted to talk about that music with him.

At the same time, I see that kind of music as carrying a strong Afrocentric lineage, so just like with blues, I didn’t feel I could simply imitate it outright. If anything, listening so deeply to artists like Ras G made me rethink, once again and very seriously, the sense of otherness inherent in blues.

So when it came to absorbing the influence of beat music in my own way, even though it doesn’t have the same surface-level stillness as ambient music, I still wanted to approach it through a minimalist way of thinking.

Over the past decade or so, there’s also been a major reevaluation of J Dilla. Were you following that movement at the time?

Okada: I actually did the opposite—I barely listened to it back then [laughs]. My interest in Ras G didn’t really come from that broader reevaluation of instrumental hip-hop. It started from a completely different thought: wouldn’t it be amazing if just the intro of a Pharoah Sanders track kept looping forever? Then it clicked — wait, isn’t that exactly what Ras G’s beats are doing?

As someone who loves records, another big factor was that I could really feel the cultural appeal of how musical legacies from the past are carried forward in this way.

So the accumulation of very material operations, sampling and editing, can paradoxically bring something like an aura back into being?

Okada: I think that’s something that can happen, yes.

You had already been working with edit-based composition on “Betsu No Jikan,” drawing inspiration from Teo Macero’s techniques on Miles Davis’s recordings. Did that experience naturally lead you to a deeper interest in sampling music?

Okada: I think it did, to a certain extent. On “Betsu No Jikan,” I was already taking performances recorded for one track, cutting them up, transforming them, and reusing them elsewhere — approaches that are very close to sampling.

But when I went back and really listened carefully to J Dilla, what struck me was how he pulls samples from places you’d never expect. And more than that, the way he uses them is completely non-formulaic. The music feels alive. Even though it’s built from edited samples, the sounds don’t exist as isolated points—they’re perceived as a flow. Materially, it’s a collection of points, but between those points there’s a dense, palpable atmosphere. Since I hadn’t listened that closely before, it all felt incredibly fresh to me.

This album also features musicians active in the jazz world, like Shun Ishiwaka on drums, Kei Matsumaru on saxophone, and Marty Holoubek on bass. Yet none of them were recorded together; each part was tracked separately. Just listening to the album, that’s almost impossible to believe. Why did you choose to work that way?

Okada: Looking back over my career, I’ve always felt that my music doesn’t fit neatly into any single framework. It has always hovered somewhere in between. This time, I wanted to acknowledge that consciously and reflect it in the method itself. I didn’t want to commit fully to collective improvisation, but I also didn’t want everything to be completed entirely inside a computer. I was interested in working within that in-between space.

That sense of in-betweenness applies culturally as well. I can’t fully commit to Black music, but I can’t fully commit to Japanese traditional culture either. And in terms of finish or polish, I deliberately avoided aiming for something completely sealed or perfect, leaving room for that same sense of ambiguity.

INDEX

Finding Connection in the In-Between

Rather than a sound that feels obsessively refined, the album seems animated by a strong sense of intuitive bricolage. Even with all the editing involved, it feels far removed from anything cleanly built through copy-and-paste.

Okada: Even when I repeat a part, I’ll run it through tape first and let the rhythm loosen slightly. I want to avoid patterns that repeat with machine-like precision. That approach connects very directly to mingei thinking. Once you become aware of the mingei philosophy, which places value on handwork, it becomes hard to justify copy-and-paste as a shortcut to save time [laughs].

I spent about a year and a half constantly kneading and reworking the session data. In some cases, a track might not sound dramatically different from its original version at first listen, but continuing to engage with the material in that hands-on way felt like one of the goals of making this album in the first place.

Since mingei has come up, when did you first encounter the idea of “Afro-Mingei,” which feels like a key motif in this album?

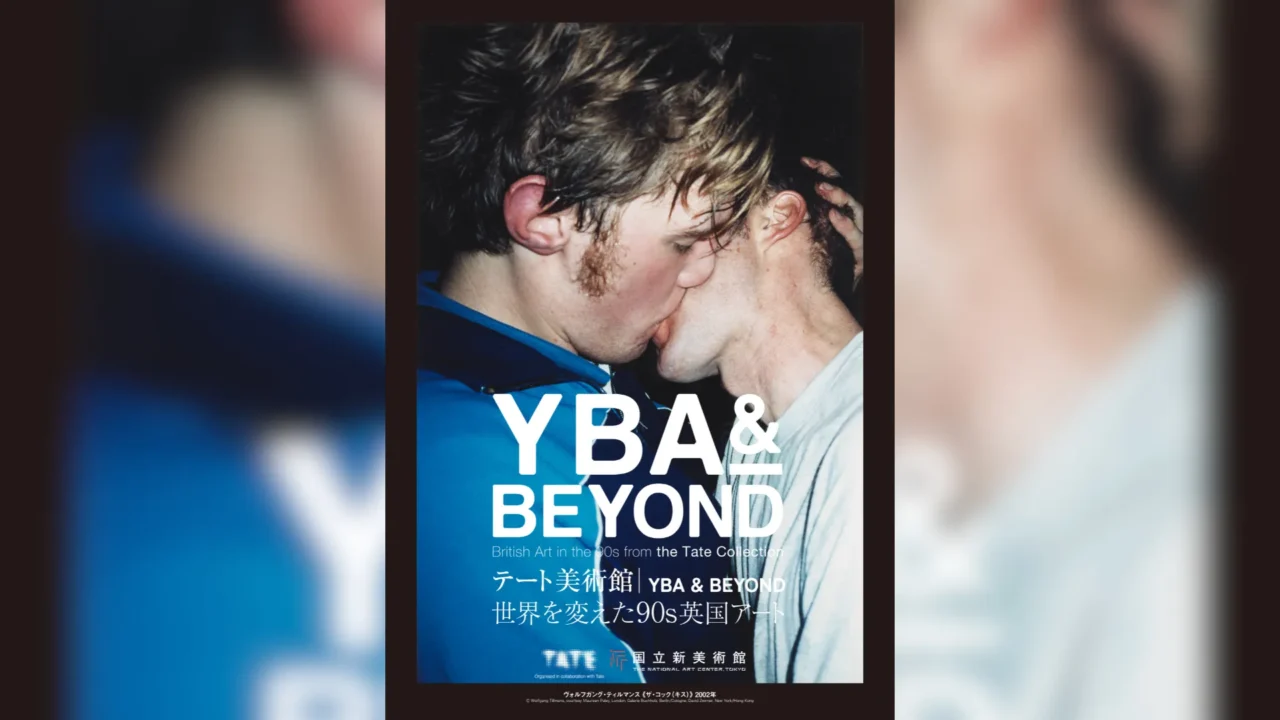

Okada: Last summer, in 2024, I was wandering around Roppongi and happened to notice that the Mori Art Museum was hosting an exhibition called “Theaster Gates: Afro-Mingei.” At the time, I barely knew who Theaster Gates was, but I went in out of curiosity. I ended up staying for an incredibly long time—probably longer than I’d ever spent in a museum before.

Afro-Mingei brings together the “Black Is Beautiful” aesthetic that emerged from the African American civil rights movement with the mingei philosophy proposed by Yanagi Sōetsu. It immediately resonated with something I had already been thinking about: the possibility of a connection between African American culture and Japanese culture.

Walking through the exhibition itself was stimulating, but what really stayed with me was how, partway through, the space suddenly opened into something like a bar or a club. In a good way, it completely caught me off guard. Rather than demanding strict contextual interpretation, it felt friendly, relaxed, and welcoming. That sense of accessibility seemed to gently draw out my own interest in mingei as well.

Did that experience then shift your attention toward Japanese or Eastern elements embedded within African American musical culture?

Okada: Yes. I’d already been interested in how Japanese motifs quietly appear in the work of spiritual jazz musicians like Pharoah Sanders and Billy Harper. But that exhibition made me think much more clearly about the potential intersections between the two cultures.

At the museum shop, I picked up Ytasha L. Womack’s book “Afrofuturism: Black Culture and the Imagination of the Future.” Learning about how African American artists have repeatedly imagined possible futures for Black culture made me want to explore what it might look like for that kind of imagination to intersect with Japanese culture as well. And in terms of how to approach that in practice, I didn’t want to become overly serious or self-critical. I kept thinking about that club-like space in the Afro-Mingei exhibition, and whether something similar—open, inviting, and approachable—could exist in music.

In that sense, “konoma” does feel noticeably more approachable than your previous album.

Okada: I sometimes feel that when you build something too rigidly, with excessive logic and precision, you end up reducing the very imagination needed to envision those “possible futures.” Seen that way, I’ve come to think that J Dilla, through his fluid and intimate music, was already giving sonic form to the idea that different cultures could connect.

Through my experience at the Theaster Gates exhibition and encountering the concept of Afro-Mingei, everything I had been thinking about—and everything I was trying to do—began to link together quite naturally.

INDEX

Drawn to Japanese Jazz Circa 1970

The album includes a cover of “Love,” originally recorded by Japanese jazz drummer Akira Ishikawa (editor’s note: the piece was composed by pianist Hiromasa Suzuki). What made you want to include this song?

Okada: It ties back to an interest I’d started developing a little before I encountered Theaster Gates’s exhibition — specifically, in the different experiments happening in Japanese jazz around 1970. Around that time, I visited the Koenji record shop UNIVERSOUNDS for the first time and spent a lot of time talking with the owner, Yusuke Ogawa, about spiritual jazz and Japanese jazz in general.

That period in Japanese jazz coincided with broader international movements, with musicians drawing not only from the U.S. but also from so-called Third World music, and incorporating a wide range of non-Western elements.

Okada: Yes, exactly. Alongside the point where free jazz experimentation had more or less been taken as far as it could go, there were many records that resonated with a more fundamental, almost primordial sense of crossover. Some musicians looked back to Afro-centric elements as a way of retracing jazz’s roots, while others turned inward, toward local traditions, engaging directly with Japanese folklore.

For example, “Gin-kai,” the collaboration between shakuhachi player Hozan Yamamoto and the Masabumi Kikuchi Trio?

Okada: There were plenty of cases where Japanese instruments were simply placed on top of easy-listening–style jazz, and I don’t necessarily dislike that approach. But “Gin-kai” goes well beyond that. It’s a remarkable record, no matter when you listen to it. Later on, ECM became known for producing cross-cultural collaborations between musicians from different backgrounds, and “Gin-kai” feels like a clear precursor to that kind of work.

Akira Ishikawa, on the other hand, is often discussed in the context of Japanese rare groove, and he also made many jazz-rock records. Still, “Love” stood out to me as having a very particular resonance. When you look closely at the relationships between musicians from that era, you start to see just how much crossover was actually taking place. In that sense, I’m drawn to both strands, and the way they reflect on musical and cultural roots doesn’t feel so far removed from my own perspective.

INDEX

Japanese Roots, Hard to Voice Overseas

Over the past few years you’ve toured the U.S. several times as a bassist with Yuma Abe. Did those experiences prompt you to think more deeply about your own cultural roots?

Okada: I’d say they were definitely a key trigger. Everyone I met, the local musicians, the staff, the audience, was incredibly kind. But whenever I was on my own, I couldn’t help but feel just how much of an outsider I really was. Being in a foreign landscape made me keenly aware of my difference, and of how unmistakably Japanese I am.

One moment that really sticks in my memory happened in Chicago. Our originally booked accommodation fell through, and we had to stay at an Airbnb in a neighborhood tourists were strongly advised to avoid. Outside the room, I could hear gunshots — just as the rumors had suggested, it was a rough area. But while driving from there to the venue, we happened to arrive on Puerto Rican Day. Puerto Rican people were everywhere, blasting music from their cars, honking their horns, and parading through the streets. Children and elders alike waved flags from their vehicles, the whole area was alive with celebration. It was unmistakably festive—a vivid expression of people enjoying themselves while celebrating their roots. Later, I learned that such public revelry also serves as a form of visible affirmation, a way of saying “we are here.”

Watching that, I suddenly wondered: why is it so difficult to engage with one’s roots in the same way in Japan?

If people in contemporary Japan were driving down the street waving flags, the meaning would be very different—likely invoking specific right-wing ideologies.

Okada: Exactly. I’m not saying I want to march around waving flags myself. But in postwar Japan, even attempting something like that would project a completely different, tense atmosphere—far from the celebratory, communal vibe I saw in Chicago.

So it made you realize the difficulty, or the emptiness and borrowed nature, of expressing one’s own identity?

Okada: Yes. At first, I was surprised by what I saw, but gradually I also felt a little envious. From an outsider’s perspective, it might look like, “why not just do the same thing?” But Japan has its own contexts, its own social traumas, that make it much more complicated.

So this album is, in a sense, a reflection on that problem—a search for your own cultural identity?

Okada: Hmm… I wouldn’t say there’s a clear answer. Rather, it’s still a process I’m thinking through, and in some ways, I consider it a kind of life work.ng project.

INDEX

Cultural Ruptures: From the Meiji Restoration to the Pacific War

The opening track, “Mahidere Birhan,” seems inspired by Ethiopian jazz and pop. Listening to it, I couldn’t help but notice its similarity to the Japanese pentatonic scale.

Okada: Living in Japan, it’s rare to encounter Ethiopian culture directly. But when I listen to their music, I sense this strange, almost uncanny connection. Why do the scales of these two geographically distant cultures align so closely? That question has fascinated people for a long time, and it sparks the imagination, just like the “possible futures” I mentioned earlier, imagining connections between African and Asian cultures. Thinking about that is genuinely fun.

It’s similar to how rumba rhythms traveled between Cuba and Africa, or how cultural expressions moved across continents. Even if the similarity between Ethiopian music and Japanese pop is partly coincidental, it’s exciting to explore these “what if” scenarios of cultural exchange.

Okada: I recently watched a YouTube program, or maybe it was a podcast, with Kenichi Shinoda, director of the National Museum of Nature and Science. He was talking about how humans are naturally migratory, and how the movement of people and objects has shaped cultures worldwide. I think a lot of popular music emerges through this same process of migration and cultural transmission.

So it’s not something that just appeared in a single fixed location.

Okada: Exactly. That’s the image I had in mind for this album, music emerging through intersections and movement. Though, honestly, on the day of the release, I suddenly thought, “Did I really take on too much?” Laughs. Still, it’s a subject you can’t avoid confronting.

And maybe that very hesitation is what makes the album such a compelling example of reflective identity exploration.

Okada: If that’s how it comes across, I’m happy with that. As widely discussed, after the Pacific War, and going back to the Meiji Restoration, Japanese popular music had to reckon with the fact that its connection to earlier traditions had been severed. That’s why, for this album, I had no choice but to think while making it, or make it while thinking.

During the Meiji era, the Music Investigation Committee promoted Western music, which gradually spread throughout society. This was part of the broader “Datsu-A Nyū-Ō” slogan, literally meaning “Leaving Asia, Entering Europe,” which the Meiji government promoted as a guiding principle for modernization across many fields in Japan.

Okada: Right. Ever since then, the imaginative potential for “Japanese-ness” in music has largely been skipped over.

In that context, it’s difficult to envision “Japanese music” in ways that are free from nationalism, right-wing ideology, or state-driven agendas

Okada: Yes.