When an author’s intent aligns seamlessly with their work’s realization, it sparks a thrilling connection. Yet, some pieces evoke profound emotions even when their creators can’t articulate their “why” or “how.” In the captivating dialogue between OGRE YOU ASSHOLE and researcher Pegio Gungi, these complexities unfold. As we explore the notion of “natural intelligence” as the antithesis of “artificial intelligence,” this article invites you to dive into a thought-provoking 100-minute conversation that examines the depths of creativity. Let’s begin with a preface by critic Yuji Shibasaki, who led this insightful discussion.

INDEX

Renowned as one of the top contemporary live bands, OGRE YOU ASSHOLE has garnered a substantial following with their mellow psychedelia. After developing a guitar sound synchronized with 2000s US indie, they solidified their reputation through a conceptual trilogy—”homely,” “100 years later,” and “paper craft”—which incorporates elements of psychedelic rock and krautrock. They have graced the stages of the FUJI ROCK FESTIVAL, performing at the WHITE STAGE in 2014 and the RED MARQUEE in 2022. In September 2024, they released their latest album, “Nature and Computer.”

INDEX

Has Music Transformed into Just “Information”?

Since when has music, which should fundamentally be a “creation,” come to feel like mere “information”? This issue likely extends beyond music itself; perhaps it’s not entirely accurate to say it has “turned into” something else. It might just be that we have become so accustomed to viewing everything as quantifiable “information.”

Nonetheless, it’s increasingly clear that musical creations are circulating as formulaic content, with only those that thrive in the competition for attention and sales being remembered, while many exceptional “creative” works slip into oblivion. This reality is becoming harder to ignore. If I were to reflect on my own susceptibility to these trends, I could only respond with uncertainty.

How can we salvage these works? More specifically, how can contemporary creators reinvigorate “creativity” in their expressions? Furthermore, how can we, as audiences—who often are creators ourselves—truly uncover “creativity” within them?

If discovering valuable insights requires us to look beyond naive critiques of capitalism, then what we need may be a different level of thinking. In this article, I will explore this idea through the lens of “natural intelligence.” Pegio Gungi, a professor at Waseda University and a Ph.D. in science, discusses this concept in his book Natural Intelligence (2019, Kodansha).

An absolute external presence that cannot be seen or heard, entirely unpredictable yet sensed, and that must be embraced when it manifests. To await something emerging from this complete externality and to find a way to coexist with it—that is the essence of natural intelligence.

——Pegio Gungi, Natural Intelligence, p. 9

Born in 1959. Graduated from Tohoku University with a degree in Science and completed the doctoral program at the Graduate School of Science at the same university. He holds a PhD in Science. After serving as a professor in the Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences at Kobe University, he is currently a professor in the Department of Advanced Molecular Science and Engineering at Waseda University. His published works include The Science of Being Alive (Kodansha Contemporary New Books), The Philosophy of Living and Raw Beings, Life No. 1, Life, Without a Tremor, Where Does the Memory of Once Living in That Game World Come From? (all published by Seido-sha), The Swarm Has Consciousness (PHP Science World New Books), Natural Intelligence (Kodansha Selected Books), It Comes (Igaku-Shoin), and TANKURI (co-authored with Kyoko Nakamura, Suiseisha), among many others.

Natural Intelligence differs fundamentally from AI (artificial intelligence), which, despite its remarkable advancements, constructs a “perceptual world” based solely on its utility and values. In contrast, Natural Intelligence patiently awaits to embrace the world, striving to keenly sense the “external.”

However, the “external” in this context does not refer to some unknown information that has yet to be learned but will be learned in the future. It signifies a thorough externality unrelated to such ways of knowing; creativity is inherently an unquantifiable endeavor achieved solely through what “comes from” that external.

Let us question once more: In a time when AI-like thought processes are rapidly proliferating across all fields, is the act of creation and the existence of art destined to be subordinate to some purpose or convenience? Absolutely not. The act of engaging in creativity with “Natural Intelligence” fully activated will surely draw in a vastly different and rich “external.”

The rock band OGRE YOU ASSHOLE is currently one of the most self-aware practitioners of this “Natural Intelligence” in their creative activities. In an interview at the time of their EP Outside the House release last year, they mentioned being greatly inspired by Pegio Gungi’s work It Comes (2020, Igaku-Shoin). Now, about a year later, their new album “Nature and Computer,” released for the first time in five years, was also inspired significantly by that book and other works by Gungi.

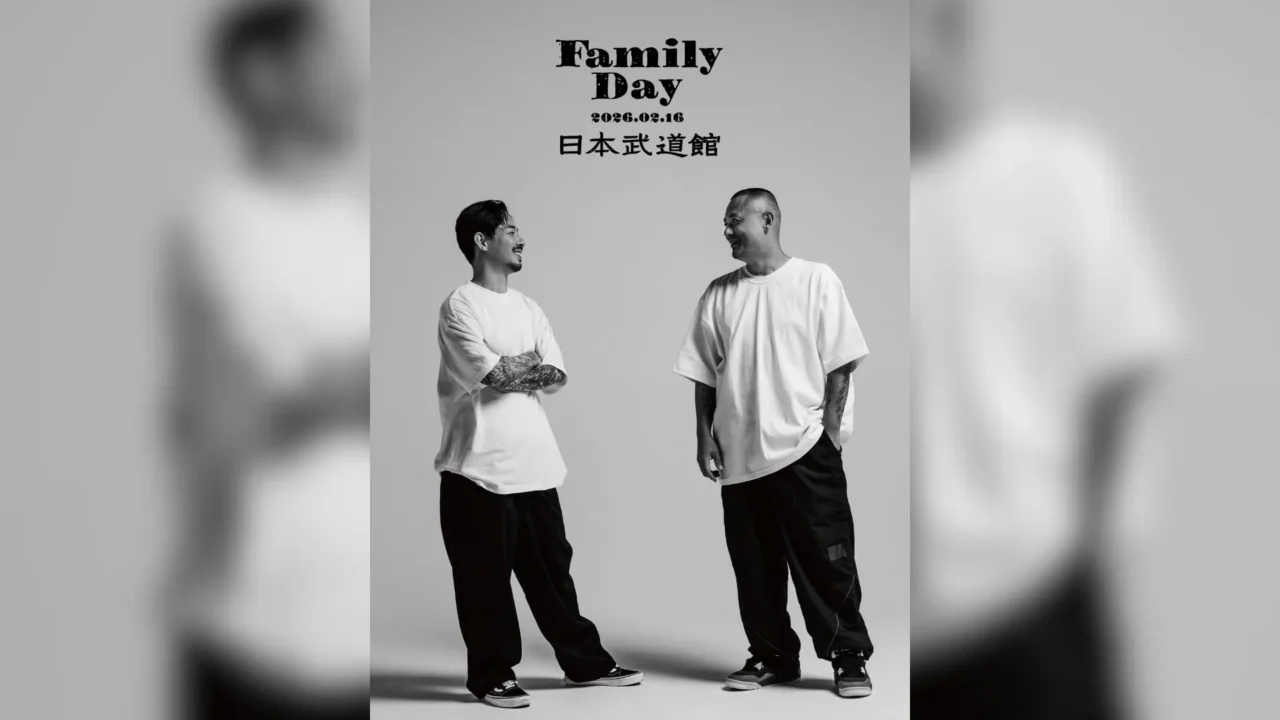

“Nature and Computer” Artwork (Available on various streaming services)

Manabu Deto, a member of OGRE YOU ASSHOLE, shared the following in an email during the planning stage of this article:

“There’s a sudden sensation of ‘I’ve done it’ or ‘I understand’ while creating, but I’m not quite sure what it is. However, it feels like it comes from the outside.”

What exactly is “Natural Intelligence”? Furthermore, what does “external” mean in the context of creativity, and what does “completion” entail in the process of making art? In this valuable roundtable discussion, we will hear from Daito, fellow OGRE YOU ASSHOLE member Takushi Katsuura (Dr), and Pegio Gungi.

INDEX

Creativity and Reality Emerge from an External Source Beyond Mind and Body

I’d like to ask Deto and Katsuura first: How did you come across Professor Gunji’s works?

Deto: At first, I think I came across a review of Yatte Kuru somewhere. It seemed like an interesting book, so I picked it up, but within ten pages, I thought, “This might be something extraordinary.” Before I even finished reading it, I recommended it to the rest of the band. I felt that it articulated things we had been thinking about in a very clear way.

Katsuura: I read it shortly after, and I felt exactly the same way as Deto. I started to think that the strange sensations I had experienced before might have been related to the “coming” experience described in the book.

What kind of experience was that?

Katsuura: I remember when I went to see Lee Perry’s concert years ago. At first, I thought it was nice music, but then suddenly a massive wave surged from the stage. It wasn’t a metaphor; it was a real “wave” unlike anything I had ever experienced before. It felt like something deep within me, neither my mind nor my body, was suddenly grabbed and I was floating in the sea, riding that wave.

So you felt a “wave” that was not just a cliché, but had a physical reality?

Katsuura: Exactly. It was an experience that went beyond just finding the music interesting; I thought, “This must be what true ‘groove’ feels like.” If I were to describe it simply, I’d say it was a hypnotic state, but for me, it was a profound event that made me realize there’s a whole other world beyond what I had previously understood rationally.

Ideto: You shared that experience with a look of astonishment back then, right?

Katsuura: I’ve been working as a psychiatrist alongside my band for some time now. A few years after that experience, while talking with a patient who had an eating disorder, I suddenly realized that I could listen to various patients’ stories with a sense of reality that I hadn’t felt before. When that patient said, “I eat to fill the void inside me,” it struck me. I thought that maybe that “void” was the same place where I had felt the “wave.”

To borrow a phrase from Gunjii, my experience of touching the limits of my previously “artificial intelligence”-like way of living made me aware of an external reality I hadn’t anticipated before.

Gunji:

That’s a very interesting episode. While the mechanisms behind eating disorders like bulimia and anorexia are still not fully understood, one hypothesis proposes the following:

Humans see their own reflection through mirrors, which gives them a first-person perspective of their face and body. However, they also construct a third-person body image by viewing their profile through double mirrors or by looking at photos taken from behind—essentially layering fragments of their image.

When the link between these first-person and third-person images is disrupted, individuals may look at their first-person reflection after dieting and losing weight, but if their third-person image remains unchanged, they might feel compelled to lose even more weight without being able to control that urge.

Expanding on this hypothesis, I believe it could also effectively explain the out-of-body experiences reported by epilepsy patients during seizures. In such cases, there might be a runaway first-person image observed from a specific coordinate, and to keep that image unified, a perspective of viewing oneself from above may arise.

Katsuura: I see.

Gunji: On the other hand, there are experiments in the field of neuroscience known as out-of-body experiments. These are quite simple: a person’s back is filmed from behind with a camera, and the subject watches this footage through a head-mounted display. In this situation, when someone touches the person’s back, they may feel as if their body is leaving their physical form.

However, when I attempted to recreate this in the lab, I found that it lacked a sense of reality. I wondered if there might be a fundamental difference between the image presented through these logical procedures and the actual experience of out-of-body sensations. In other words, the reality referred to here might also be something that comes entirely from an external source.

Katsuura: That is very interesting.

INDEX

The Moment of Completion: When Does a Work Truly Finish and What Gaps Remain?

Gunji: I believe that the practice of art also relies on something that comes from the outside in the same way. It’s not simply about saying, “This is why the expression turned out this way”; rather, art serves as a device that invites us into an experience of sensing the external.

In other words, it’s crucial that a collection of first-person expressions isn’t just parallel but instead has an “opening” that allows it to extend into the external realm. I realize I’ve taken quite a roundabout way to get here… [laughs], but listening to OGRE YOU ASSHOLE’s music in preparation for this discussion made me feel that very sense of “art” in that context.

Deto: That’s great to hear. When I’m making music, there are moments when I suddenly think, “Ah, I’ve got it,” and I feel that relates to what you just mentioned. It’s not about having a completed vision in mind and actively working towards it; rather, it often comes unexpectedly while I’m simply playing the synthesizer or experimenting with sounds. It’s a sensation that can’t easily be put into words.

I can’t quite explain why I consider that moment as “complete,” but there’s definitely a sense of satisfaction. In Kato’s book Where Does Creativity Come From? — The World of Natural Expression (2023, Chikuma Shobo), he discusses how being thoroughly passive can lead to an active state of creation. I wonder if that state is somewhat similar to what I’m experiencing.

Gunji: As long as we live with self-awareness, it’s challenging to be completely passive; we inevitably maintain some active attitude. I believe it’s within this contradictory situation that creative acts become possible.

This idea doesn’t involve reaching a profound “enlightenment” through special training; rather, it can often occur in everyday situations. In that sense, the song “Outside the House,” which sings about a passive state of “waiting,” captures this feeling well.

Deto: That makes sense. I can’t articulate it precisely, but during live performances, I often find that when unexpected troubles arise instead of sticking to a pre-planned blueprint, the performances feel more genuine.

That’s why I intentionally include ambiguous parts in songs I’ve practiced many times. It’s as if I’m playing an unfamiliar piece, which brings me closer to the state you mentioned, where something emerges that can’t be measured by the usual concept of “high-quality performance.”

Katsuura: I get that. I’ve always disliked “skilled music” as a premise (laughs). When I listen to music that highlights the players’ technical abilities, I feel like “nothing is happening here.”

I used to have the desire to play the drums exactly as I wanted, but I’ve realized it’s impossible to play perfectly when my body is involved. Recently, I’ve come to find it interesting precisely because I can’t play exactly how I envision. In the past, I would try to eliminate any muddiness in the band’s rhythm during performances, thinking of it as noise, but in recent years, I’ve come to believe it’s better not to force everything to fit perfectly.

Gunji: I also create sculptures, but I’m at a stage where I can’t quite say, “I shouldn’t focus too much on technique,” so I recognize it might come off as presumptuous (laughs).

I believe a true artist is someone who can pinpoint the moment they think, “Ah, this is done.” In contemporary art, influenced by postmodern theories, there’s often a notion that the creative process involves continuously delaying that sense of completion. However, I believe there are still creators who experience a definitive moment of realization: “Ah, it’s finished.”

Even if outsiders perceive it as incomplete, the creator undeniably reaches that point of clarity: “This is complete.” I think that’s what enables them to carve out an “opening” in their work that connects to the external world. The objective reality of what that means is something that can’t be captured within an artificial intelligence-like framework.

INDEX

The Inherent “Opening” of Art and the Sense of “Lame Coolness”

If we consider the earlier discussion about live performances, it may be that by embracing the imperfect state of having “openings,” we can feel a sense of “we’re playing well” as participants.

Deto: Ah, that might be true.

Gunji: The “openings” we’re talking about can manifest not only in static artworks but also in forms like music performances. The key point is that these “openings” represent absence in the literal sense; they cannot be manipulated or treated as if they were present. Instead, they emerge from the incomplete state of tension and inconsistencies experienced by the participants.

Deto: Definitely. Rather than consciously thinking, “Let’s create an opening here,” we tend to feel more like we’re just providing a free space within the song. We place those parts as a catalyst from the outside and use them to experiment with various things. In reality, we won’t know what will happen until the entire band faces that free situation together.

How about you, Katsuura?

Katsuura: Our songs often have repetitive structures, which sometimes leads to them being labeled as “mechanical.” However, that feels overly simplistic to me. Take Kraftwerk, the pioneers of techno music: while they project a mechanical image, you can still hear nuances of human performance, like imperfections and slight delays. Personally, that’s where the appeal lies for me.

Recently, OGRE YOU ASSHOLE has been playing along with electronic sounds, but I don’t think it’s possible to be perfectly synchronized with machines, nor do I want to be. The moments when there’s a bit of a “squishy” disconnect between us and the machines are what I find interesting. It’s almost like we consider the machines as part of the band while we play.

So you believe that it’s in those gaps and discrepancies that the musical dynamism resides?

Katsuura: Exactly, that’s what I think.

Gunjii, you also mention gaps and discrepancies in music, using artists like Prince as examples in your book やってくる. I found your use of the term “awkward coolness” to describe this appeal quite striking.

Gunji: At first glance, “awkward coolness” might catch people off guard… [laughs]. What I mean is that when we think of something as “cool,” it often refers to a perfectly aligned arrangement of components with no flaws. In contrast, “uncool” describes a state where that arrangement is mismatched.

To take it further, when unrelated elements are simply placed together, that’s what we call “lame.” On the other hand, “awkward coolness” involves a mixture of disjointed elements that somehow maintain a sense of coherence.

I believe that “awkward coolness” arises from the effective introduction of disconnection by inherently unrelated entities, creating an unclear but intriguing state. And I think this is crucial for the act of creation itself.

Deto: I find this really fascinating, and I can instinctively grasp the feeling.

Gunji: When we view pure entertainment and art as distinct concepts, I’m not necessarily criticizing the former. Entertainment often mixes highly disparate elements within a closed environment while maintaining a sense of coherence, yet it doesn’t seek to connect with the outside world.

On the other hand, I think art fundamentally dismantles that structure and forges connections with the external. Prince’s work is generally seen as entertainment, and when I first watched his music videos on a friend’s recommendation, I thought, “This is so lame!” [laughs]. However, after watching them multiple times, I started to realize, “This is actually incredible…” and I was genuinely moved.

Prince has many works that exemplify this, and I think it’s an important point that playing with machines often highlights those “gaps.” When I consider that, it feels like recent uses of electronic instruments by OGRE YOU ASSHOLE carry a sense of “awkward coolness” [laughs].

Katsuura: If that’s the case, I’m glad to hear it [laughs].

Instead of using easily controllable digital instruments that produce diverse sounds, you actively choose cumbersome analog gear like modular synthesizers. What’s the reasoning behind that?

Deto: I’m not sure. At least on a sensory level, analog synthesizers seem to produce better sounds than digital ones.

Katsuura: Right, and among analog synths, those that require retuning every ten minutes to keep their pitch can actually sound better.

Deto: Exactly. It’s a strange phenomenon.

INDEX

Emphasizing “Being a Cat” Over “Not Being a Cat”

With this in mind, the title of the new album, “Nature and Computer,” becomes particularly fascinating. It implies that we aren’t seeing it as a simple binary of “Nature or Computer,” but rather as “Nature and Computer,” or “Nature alongside Computer.”

Gunji: I think this is a very insightful point. In AI research, it’s not enough to simply aim for fast, high-capacity artificial intelligence; there is a discussion about needing to envision a thorough connection with the external world that transcends the dichotomy of computers and nature. The importance of interfaces that connect the two is also well recognized.

In music production, for instance, those who have a deep fascination with microphones embody a viewpoint that transcends this binary framework.

Gunji: Absolutely. This can also be seen with train enthusiasts, who have a strong interest in trains as materials while simultaneously feeling a connection to nature through aspects like paint quality and the texture of the metal. This perspective transcends the simplistic view of “Nature or Machine.”

Gunji: You know those comedic “common experiences” jokes, right? Like, “Whenever you point a camera at a ramen shop owner, they always cross their arms,” or something like that (laughs). I don’t think every ramen shop owner actually does this; it’s probably a much smaller number. Maybe someone saw just one owner doing it in the past, and that impression got generalized. Yet, we all tend to think, “Ah, that’s so true!”

What’s happening here is that the opposing framework of “Ramen shop owner A crossed their arms, but ramen shop owner B didn’t” gets confused with the framework “Ramen shop owner A crosses their arms, and ramen shop owner B also crosses their arms.” The distinctions of “A or B,” “A either B,” “A and B,” and “A both B” blend together in a way that feels integrated, which is why these common experiences work as comedy.

Deto: That’s interesting.

Gunji: Nature exists as a thorough external entity in this context. On the other hand, computers, as computational devices, are present in front of us as things we can ideologically manipulate. When we reconsider the “and” in the title “Nature and Computer,” I believe that the existence of analog synthesizers, which are notoriously complex to operate, serves as a means to connect with that external reality beyond a binary opposition.

Katsuura: When I first heard the album title from Deito, I felt something interesting, even though I couldn’t quite explain why. I think it resonates with the lyrics that Deito writes as well. Perhaps he writes them without fully understanding himself.

Ideto: Exactly, that’s it [laughs].

Katsuura: Your analysis of the album title is insightful, but it also makes me think about the challenges of logically explaining those unclear, ambiguous feelings in your books like Yattekuru, Tennen Chinou, and Where Does Creativity Come From? — The World of Natural Expression. I feel like there are gaps within these texts that serve as devices for things to “come forth.” Take the comment by Makoto Yoro on the cover of Tennen Chinou, where he says, “It appears to be simply written, but don’t underestimate it. It will change your perspective on the world.” To me, it doesn’t feel simple at all. I think it’s a book that reveals something new every time I read it.

Deto: Gunji’s writing certainly provides a lot of inspiration from a creative standpoint, but it also resonates with the moments we experience in our daily lives. I think it relates to the earlier discussion about “common tropes,” especially in Yattekuru, where you explore how we recognize a single cat as a “cat.” That was particularly fascinating.

It discusses how, when we encounter a specific cat, we are merely judging it as “more of a ‘cat’ than ‘not a cat.'” It suggests that the potential realm of what “is not a cat,” which is dismissed as external, actually establishes the reality of the cat itself. Reading that part made me go, “Ah, I see!” and I found it exhilarating.

Conversely, there can be moments when we sense the potentiality and randomness of existence in all things.

Gunji: For instance, if there’s a can of cola in front of me, it retains its reality precisely because of the potentiality that it “might not be a can of cola.” Returning to the topic of creativity, I believe that unless we can understand, at a daily level, that something we cannot even imagine can “come forth,” it will be difficult to grasp the true meaning of creativity.

Deto: I truly feel that way as well.