To mark the completion of ROTH BART BARON’s latest album “8,” Masaya Mifune released his first photo book featuring new images titled “RBB ‘ZINE’ BEAR MAG vol. 3 – ‘8’ Photo Book” (with CD). Simultaneously, an exclusive exhibition called “Music and Graphics #002,” celebrating this project in collaboration with six creators—Tsuguya Inoue, Yuri Kaminishi, Ken Okamuro, Kishomaru Shimamura + Maiko Higuchi, and Yoshiko Fujita—is taking place from November 9 to December 17 at OFS TOKYO in Ikejirioohashi.

Among the six collaborators, Kishomaru Shimamura stands out as the lone photographer and artist whose primary domain is photography. Much like Mifune, who actively engages in various fields centered around music and photography, Shimamura participates in a diverse range of expressive endeavors, including the establishment of a ramen store, a fragrance brand, and the management of a gallery. In our planned conversation, we delve into topics of photography and music, exploring the origins of their creativity that allows them to seamlessly navigate the world and produce works that transcend a singular form of expression.

During the discussion, the two artists coincidentally appeared with the same camera for a project involving “capturing each other’s pictures.” Starting with a leisurely stroll through the exhibition site, the conversation unfolded harmoniously. They touched upon their latest creations, reflections on the impact of the pandemic, insights gained from their experiences abroad, and the discovery of the enchantment prevalent in the world—ultimately forming the foundations of their artistic expressions. At its core, the discussion emphasized the significance of being attuned to the subtle magic present in the world.

INDEX

Kishomaru: Mifune’s Photographs are Akin to Music. It Possess a Private, Novelistic Quality while Maintaining an Overarching Perspective

Born in Tokyo, Japan. He formed ROTH BART BARON in 2008. Currently based in Berlin, Germany and Tokyo, he will perform at “FUJI ROCK FESTIVAL” for the second time in 2023.

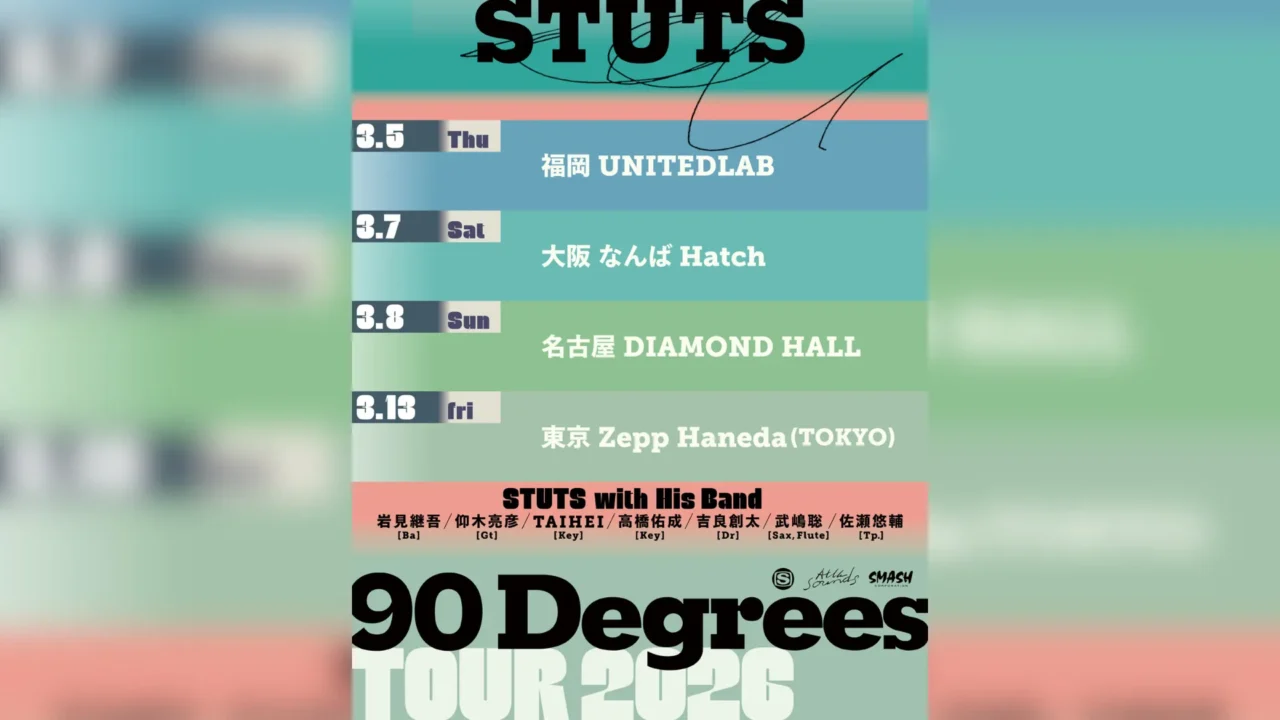

In 2021, “BLUE SOULS” by A_o, a duo of artists with Aina the End In 2022, he composed the music and theme song for the movie “My Small Land,” which won the Amnesty International Film Award at the Berlin International Film Festival. He is currently on a 13-concert national tour starting in November, entitled “ROTH BART BARON TOUR 2023-2024 ‘8’”.

The weather was ideal for capturing shots during a leisurely walk.Do both of you often take photos while walking like this in your daily routines?

Mifune: I often take pictures of scenery I find interesting while strolling around town. This photo book also contains photos of sparkling discoveries I have made in my life since moving to Germany.

Kishomaru: When I take photographs, I usually do the same thing, and I try to take an honest look at the scenery in my daily life that catches my attention or that I find “nice” in a phenomenon.

Born in Tokyo. Artist. Photographer. He is active both in Japan and abroad, not only in photography, but also as a co-chairman of the frenzy brand kibn, Ramen Kichoshomaru, and SAME GALLERY. His solo exhibitions include “Unusual Usual” (Portland, 2014), “Inside Out” (Warsaw, 2016), and “photosynthesis” (Tokyo, 2020).

While capturing images on the move, there appears to be a shared affinity for certain scenes between both of you. Interestingly, the fact that both of you are using the identical Makina medium-format film camera is quite astonishing.

Kichijomaru: I was surprised too. And not only the makina 67, but also the CONTAX compact camera that they brought as a sub was exactly the same.

Mifune: Actually, yesterday, I was just hanging out at a coffee shop in Nakameguro when Mr. Kichijomaru happened to pass by on his bicycle and dashed right up to me (laughs). (Laughs.) That was the first time we met, but it really is full of strange coincidences, isn’t it?

Maybe that’s the reason why I felt an instant connection again today. Nonetheless, this marks our inaugural collaboration in crafting art together. Kishomaru, what were your thoughts on Mifune’s photographs?

Kichijomaru: I came to know of Mifune’s existence through music, so in that sense, I thought his photographs were wonderful and not at odds with his musicality. I felt that the smell from the photographs and the smell from the music were the same. The photos are like a personal novel, but they also have a bird’s-eye view, and the underlying idea of Mifune’s own expression and recordings is consistent. I also take a lot of photos in my daily life as an independent photographer, so I felt a similar perspective from the photos that I could identify with, “This is a moment I couldn’t help but take a picture of.

As part of the ongoing exhibit ‘Music and Graphics #002,’ six artists, drawing inspiration from tracks on ROTH BART BARON’s latest album ‘8,’ have individually produced artworks centered around a chosen song. Kishomaru, would you mind discussing the specifics of the piece you’ve created for this event?

Kichijomaru: I looped “8” over and over and chose the song “Boy. I had a hard time deciding, and in the end I chose it on a hunch. If I had to give a reason, it would be because the lyrics are very abstract. If I had to give a reason, it would be because the lyrics are often abstract, and I did not want the photos to embody the lyrics and define something. This time, we also have a collection of Mifune’s photographs, and I thought we should create something that has a slightly different atmosphere from his work, but also has a margin to accompany “8”.

Kichijomaru: While the other exhibitors this time were all graphic designers, I was in the unique position of being the only photographer like Mr. Mifune, and as I thought about what I could do, I ended up choosing “a photo of a boy’s backside,” which echoes the title of the song. In the end, I went around in a circle and chose “a photo of a boy’s backside” as the title of the song.

Mifune: Many of Kichijomaru’s photographs are of fleeting moments that drift in and out of relationships. There is a gentleness to them, but there is also a sense of distance. I like the perfect balance of softness and tension. Actually, I haven’t seen his works yet because I didn’t want to see them until the exhibition started, but knowing that kind of charm, I am looking forward to seeing how the works will turn out when they meet “Boy”.

INDEX

Mifune’s Reflection on Moving to Germany and the Intrinsic Connection to the ‘Juvenile’ Theme: “We are Driven Solely by Personal Joys and Discoveries“

In both this photography collection and the overarching theme of the new album ‘8,’ the spotlight is on ‘Juvenile.’ Although often associated with the literary and cinematic genre portraying children’s adventures, the term fundamentally signifies ‘youth.’ Masaya Mifune, what led you to select this theme for your current projects?

A confluence of various timing factors led me to create a film with a juvenile theme this time, although the concept had been lingering vaguely in my mind for over a decade. Despite the turmoil of the world amidst the pandemic and conflicts, witnessing children happily playing amidst the chaos struck me. It made me realize that, for them, the joy derived from new discoveries and friendships forged through their adventures surpassed the tumultuous state of the world itself. Ultimately, I came to the conclusion that people are propelled by personal joys and discoveries, not necessarily “for the world.”

This realization has been particularly poignant since my move to Germany this year. Embarking on a new life in Berlin, I encountered a plethora of personal discoveries and joys—unconventional rules and values, breathtaking scenery, and the forging of new friendships, to name a few. The list is endless. Having previously explored global perspectives in my last three films, I found the prospect of creating a film with the theme of “I don’t give a damn about the world” intriguing. The word ‘Juvenile’ encapsulates this sentiment.

Examining the lyrics of the initial track, ‘Kids and Lost,’ along with the concluding statements in the photo collection, I perceive a theme that touches upon a sense of unease regarding adherence to societal norms in Japan.

Mifune: Juvenile fundamentally narrates the journey of children transitioning from outsiders to integral parts of the broader society, signifying the conclusion of childhood. This involves either rebelling against adults and societal norms or, conversely, aligning with adults to confront something greater. Within this process, there exists a counter approach to elements shaping them—be it through conflict or evasion. This contrast is vividly portrayed in ‘Kids and Lost,’ perhaps reflecting an opposing stance to the Japanese society that has influenced my own formation.

So the experience you gained from living in Germany was a big part of your work.

Mifune: What was good about moving to Berlin was that I realized that I did not need to belong to society to that extent and that I could focus more on my personal awareness. I feel that in Japan, there is an aspect where people who can change their own form to fit the values held by the majority of society are valued.

Kichijomaru: I used to live in Portland, so I understand this feeling. When you live in Japan, society imposes the concept of “the norm” or “everyone else” on you. However, the scope of such concepts is extremely narrow. I think that originally, people were doing what they thought was good for everyone to feel good about themselves.

Mifune: Yes, yes. What surprised me when I came back to Japan was the overwhelming number of messages trying to control people, such as “Don’t stand in front of the door of the train or station,” “Don’t look at your cell phone,” and so on. What surprised me the most was that in the park behind my house, a kindergarten teacher lined up all the children in a row and told them not to climb trees or throw stones. There was no such scene in Berlin.

The three years grappling with the challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic before your move must have left a lasting impact. Now, as it gradually recedes, exhibitions and live events are resuming in a manner reminiscent of the past. How does this transition make you feel?

Mifune: After three years of masking in Corona and seeing the audience nervously listening to our music, we tried to destroy it, but now that we are in a world where everyone can come into contact with each other again, I feel that everyone cannot feel happy without a place where they are physically connected like at a live show. I think that’s what I want to focus on. That is what I want to focus on again.

Kichijomaru: The prevalence of digital communication is undeniable, offering its natural advantages. However, there seems to be an innate human yearning for an analog, physical connection. Consider a physical “house” in a specific location—while some might see it as merely a “house,” there’s a growing need for the concept of a “home.” This concept implies a place where tactile connections are fostered. Instead of solely striving for artworks deemed “good music” or “good photos,” it’s crucial to explore questions and engage in dialogue centered around the concept of “home” and the local community to which we are physically connected. Mifune adds, “As long as we are human beings, we must be able to communicate with each other.

Mifune: As long as we are human beings, I think we must have such tactile connections. ROTH BART BARON also does not have a gallery, but has a community of supporters called “Palace,” in which anyone can participate. The people at the Palace help us design our merchandise and sell items at our live shows. It is true that you have the image of creating a “home” or a small town, or even a village.

INDEX

Crafting Uniqueness: Kishomaru on Creating in a World of Beloved Works

What defines a ‘work physically connected to resonate with this place and these people’?

Mifune: “A work that is part of the everyday, but that also manages to transcend the everyday. For example, in the case of a photograph, there is the intention to not only capture what is there, but also to capture what is there from the perspective of Mr. Kichijomaru, if it is Mr. Kichijomaru, or me, if it is me. If I were you, I would have the intention to photograph what was there from your point of view, and if I were you, I would have the intention to photograph what was there from my point of view.

Aspiring to surpass the ordinary. In which moments does this intention come to fruition?

Mifune: When I am taking pictures or thinking about a song, a certain scene comes to mind, and I sometimes feel a strong primal will to reach it. Poetry, too, is ultimately output as language, but I rather have a nonverbal image board at first, which I later put into words. I take pictures, play instruments, and sing songs because I want to capture the moment. You might think that my work is message-driven, but in fact, it begins with a very non-verbal and vague image.

Kichijomaru: I also have many vague concepts that I am always thinking about in parallel in my mind, and when I happen to connect with the right time and the right people, they become concrete projects such as fragrance brands, ramen noodles, and galleries. Perhaps it is the same as Mr. Mifune’s, something non-verbal and ambiguous that is at the root of my ideas.

Mifune: I already have an idea of what I want to create, so I just have to do it. More specifically, my intention turns into an idea, and before I know it, I have started to create something. To use a simple analogy, in my case, there are always about 10 trains of ideas running, and I am always driving one of them. And when that train is about to reach its destination, I jump on the train running next to it. At the end of the day, I can leave it alone and it will go to its destination on its own.

“Juvenile” had been running next to me for about 10 years, but I never had a chance to jump on it. But when I went to Germany, the moment that the “personal discovery and joy” I mentioned earlier applied to me, I felt like I could do it now! And I jumped on board in a hurry.

Kichijomaru: The expression “jumping on a running train” is interesting. To borrow the train example, I think it is possible that the trains are actually running on the same track when you look back at them. When I exhibit, I research papers, history, and past works by other artists related to the concept. For example, I may find a work in a photograph I took intuitively long ago that has the same scent as the concept I was thinking of at the time. I feel that trains do not always run on the same track, but rather cross, split, and change from time to time.

Mifune: There are times when trains are connected, as if by magic. In fact, the song “Closer” in “8” was written at the beginning of Corona with the idea of creating a song that could be danced to, but I didn’t feel like I could sing it for three years in a world where I couldn’t dance, so I didn’t release it. But when Corona dawned in 2023, I felt that I had to include it in “8” as if it were a puzzle that fit together. Somehow the lyrics also fit “Juvenile” perfectly.

It feels like you’re unconsciously being pulled towards the train.”

Mifune: I guess I am no longer driving the train. If anything, I am being controlled by the train (laughs).

Kichijomaru: That may be so. This is connected to what I said earlier about the intention at the starting point of creating works, but there are moments when it becomes clear to me why I have to do it, even though there are already musicians and photographers in the world that I like. The moment when you realize that you are compelled to take this picture rather than that you have to take it ……. I realize that I am the only one who can see the beauty in this place at this moment. By connecting that ambiguous and intuitive thing with the concepts and thoughts of the work I have been thinking about, I think I am able to create the work.

Mifune: To borrow a phrase from Mr. Kichijomaru, it is whether or not you can notice a little magic in the world that only you can notice. And once we become aware of it, we amplify the charm of that “magic in the world” by creating songs, taking photographs, and outputting it through our own perspectives and intentions.