Monet – the name that instantly brings to mind serene Water Lilies and the brilliance of Impressionism. His works are beloved, especially in Japan, where his paintings resonate with so many. But while the world is familiar with his iconic blooms, a special exhibition is shedding new light on a lesser-known chapter of Monet’s career.

At ‘Monet: The Water Lilies’ exhibition, held at the Kyoto City Kyocera Museum of Art, over 20 versions of his famed Water Lilies are on display. A massive celebration of Monet’s later works, this is touted as the largest Monet exhibit ever held in Japan. While Monet exhibitions seem almost ubiquitous, this one promises something unique, described boldly on its website as ‘The Ultimate Monet Exhibition.’

But this isn’t just another retrospective. The focus here is on Monet’s later years – a period that was once overshadowed by his early masterpieces, and often neglected in the past. Now, however, these later works are enjoying a resurgence in appreciation. For Monet aficionados like us, it’s the perfect opportunity to refresh our perspective on the master’s legacy.

In this article, I’ll share my experience from the Tokyo exhibit that captivated 800,000 visitors, and dive into the must-see highlights of this extraordinary display.

INDEX

Reflections in Water: The Continuation of the ‘Water Lilies’ Series

As the exhibition focuses on Monet’s later years, by the time of Chapter 1, Monet is already in his 50s. He had long ceased participating in the Impressionist exhibitions and was fully absorbed in creating art and tending to his gardens at his countryside estate. In this section, you’ll find works that center the surface of the Seine River, showcasing compositions that capture both the real landscape and its reflection. Monet’s fascination with painting the reflections on the water would eventually lead him to the famous Water Lilies series.

One thing that can only be truly understood by seeing the artwork in person at the museum is the subtle shading created by the artist’s brushstrokes. When facing the actual piece, you can see that the lower half of the reflected landscape on the water is covered with continuous brushstrokes, such as “— — —,” which allows the viewer to recognize, “Ah, this part is reflected in the water.” However, this is sadly something that can’t be captured by media… perhaps it could work with ultra-high definition? In the series depicting the water lilies, the sideways brushstrokes also serve as a clue for distinguishing the reflected images on the water, so I encourage you to observe them up close.

In Chapter 1, there are also other works depicting river landscapes, and the series of paintings of the “Charing Cross Bridge” over the Thames in London is a must-see.

INDEX

Peering into the Creative Process

In the preliminary studies, Monet briefly captured the floating water lilies and the reflections of trees on the water’s surface using only a few subtle colors. On the other hand, in the adjacent Water Lilies painting, the same composition is retained, but the water’s surface is tinted in red and orange, revealing that it was the vivid sunset scene that truly captured Monet’s attention. It’s almost like a before-and-after transformation in a coloring book. What surprised me was that, despite being inspired by such a scene, the artist didn’t use any colors associated with dusk in the initial sketches. Once the composition was set, it seems the colors that were firmly imprinted in Monet’s mind were quickly and confidently applied. Interestingly, it’s said that there are about 15 variations of this composition.

INDEX

Monet’s Floral Paintings Beyond the Water Lilies

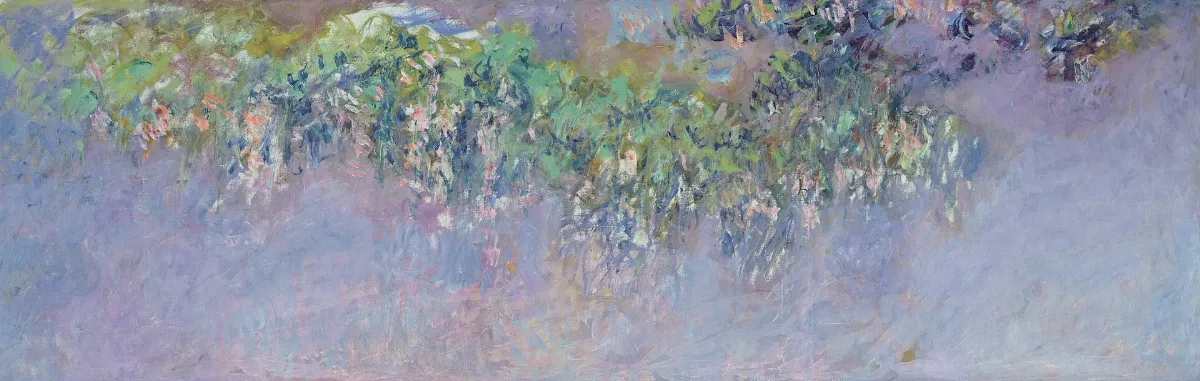

Chapter 2, “Water and Floral Decorations,” showcases Monet’s works featuring flowers by the water’s edge. Notably, two preparatory studies of wisteria flowers stand out. These were initially intended to be part of the “Grand Décor” project as friezes (long horizontal decorative bands) at the top, though they were later abandoned.

The “Grand Décor” was a grand project in which Monet envisioned large panels depicting the water lily pond, designed to cover the walls of an oval room. This project became one of Monet’s greatest passions in his later years. In today’s terms, it might be called an “installation: Water Lilies.” Looking back, Monet could be seen as a pioneer of immersive art experiences, a concept now widely popular. After Monet’s death, his vision was realized at the Orangerie Museum in Paris, where the special exhibition rooms were created.

Personally, the two “Wisteria” pieces were the most striking to me in the exhibition. Seeing them in photos might not do them justice, but the light purple mist that appears to have been the final layer, swaying gently, almost seems to sing. It has a vibrant and mysteriously rhythmic quality, reminiscent of the “golden clouds” often seen in traditional Japanese painting. Although the wisteria frieze was never completed, I can imagine it would have brought immense happiness to many had it been realized.

On the other hand, this piece would undoubtedly win the “Must-See in Person” award. The green band that flows diagonally across the painting, said to represent the twilight light, was described by critics as resembling “melted gold.” When I read this explanation in the exhibition, I agreed wholeheartedly, but when I later saw the image of the painting, I was shocked. It only looked green to me… Where did the water lily I saw that day go? I searched the catalog, looked it up online, but I couldn’t find it anywhere! It left me with a feeling of helplessness. Among all the emotions that art evokes, the impact of color is especially fleeting. The artwork I saw created an image within me in that very moment and place, and it only exists there. I realized this simple truth: even though Monet’s works are so familiar and abundant in my mind, the emotional experience born from viewing them only exists in that specific encounter.

INDEX

Chapter 3: The Path to the Grand Decorations – Surrounded by the Large-Scale Water Lilies

Chapter 3 features the highlight of the exhibition: an oval-shaped space reminiscent of the Musée de l’Orangerie. Eight large “Water Lilies” works, each over 2 meters wide and created during the production of the “Grande Décoration” project, surround the viewer in this immersive setting. The image is an official, crowd-free photo, but in reality, this exhibition room was filled with visitors, as it was the only area where photography was allowed. While the experience leaned more toward connecting with fellow Monet enthusiasts than focusing solely on the artworks themselves, it was still an enriching experience. It’s worth taking the time to find moments to step back, maintain some distance from the pieces, and truly enjoy the artworks, as these “Water Lilies” are impressively large.

The water lilies on display here were painted after 1914, and they show a wide range of variations. While the compositions may appear similar, the mood of each piece shifts dramatically depending on the time of day and the weather. Monet had expressed in 1908, “I’ve become captivated by water and its reflected landscapes. It’s a heavy burden for my aging body, but I still long to capture what I feel.” And even after all these years, it’s evident that his obsession with the water lilies never faded. In fact, his deep fascination is so evident that viewers may find themselves bewildered, realizing that Monet had, in no way, grown tired of painting the lilies.

Since it was hard to step back, I decided to try capturing the image from a closer perspective. The short red lines, subtly connected, hint at the contours and shading of the slightly lifted leaves. Now, which piece of the four shown above does this section belong to?

INDEX

Monet’s Last Years: A Symphony of Colors

The exhibition culminates in its highlight. In Chapter 4, “Symphonic Colors,” visitors are introduced to Monet’s later works from after 1918. While the over 20 “Water Lilies” paintings are remarkable, the intensity of this section is equally compelling. The works are all small series, with the ones shown in the image above featuring the same composition of the garden’s arched bridge. Compared to Monet’s earlier series, like the haystacks, the colors and brushstrokes here are strikingly bold.

In the depiction of the drum bridge, it may be difficult to discern what’s being portrayed unless one consciously reminds themselves of its subject. Monet, despite battling color vision issues and declining eyesight due to cataracts, never lost his creative drive as he approached 80. The sweeping brushstrokes seem to reflect the very movement of Monet’s own body as he painted. Rather than simply viewing a painting of the drum bridge, one might feel as if they’re witnessing the act of painting itself—Monet’s determination and passion laid out before them. This is one reason why his late works have been reinterpreted as early examples of abstract expressionism, akin to the work of Jackson Pollock.

Monet’s final series, The House Seen From The Rose, is also on display, with four out of the eight paintings from the same composition gathered together. The second piece from the right, with its beautiful scene where the orange glow of the sunset seems to cover everything, stands out.