INDEX

A Legacy Preserved: The Family’s Role in Bringing Sakamoto to the Screen

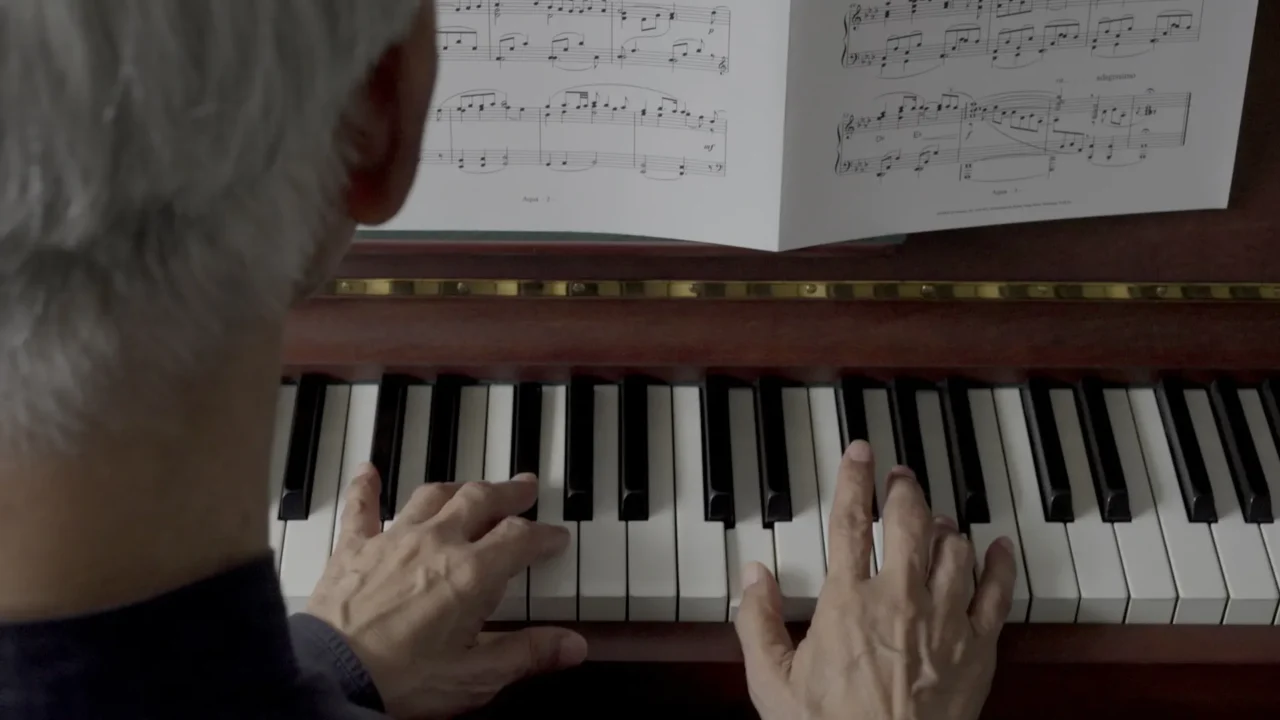

In the final scene of the film, there’s a close-up of his hands and a caption that isn’t from the journals or narration. Is that your interpretation as the director?

Omori: That isn’t my words… The footage was provided by his family, who were present at that moment, and they suggested those words. When it comes to preserving the last three and a half years of someone like Ryuichi Sakamoto, a figure almost like the embodiment of music, I think the film naturally arrives at that ending.

Looking at the film as a whole, it’s quite a feat, balancing everything so delicately.

Omori: It was definitely challenging. At times, looking at all the materials and emails, I wondered if we could really complete it.

As the director, I ultimately handled various tasks and editing, but this film involved many people: Sakamoto’s family, friends, doctors who supported him in his final years, and the team that produced the NHK Special. Still, there are aspects only his family, who were with him until the very end, could truly understand.

As the director, what motivated you to complete this film?

Omori: I think it was a matter of connection—or maybe I just happened to witness something extraordinary. If I call it a sense of mission, that sounds a bit dramatic… but really, I was moved by the power of the records that had been left behind. By chance, it happened to be me who received them. I’m grateful for that coincidence, that environment, and the circumstances that allowed me to take part.

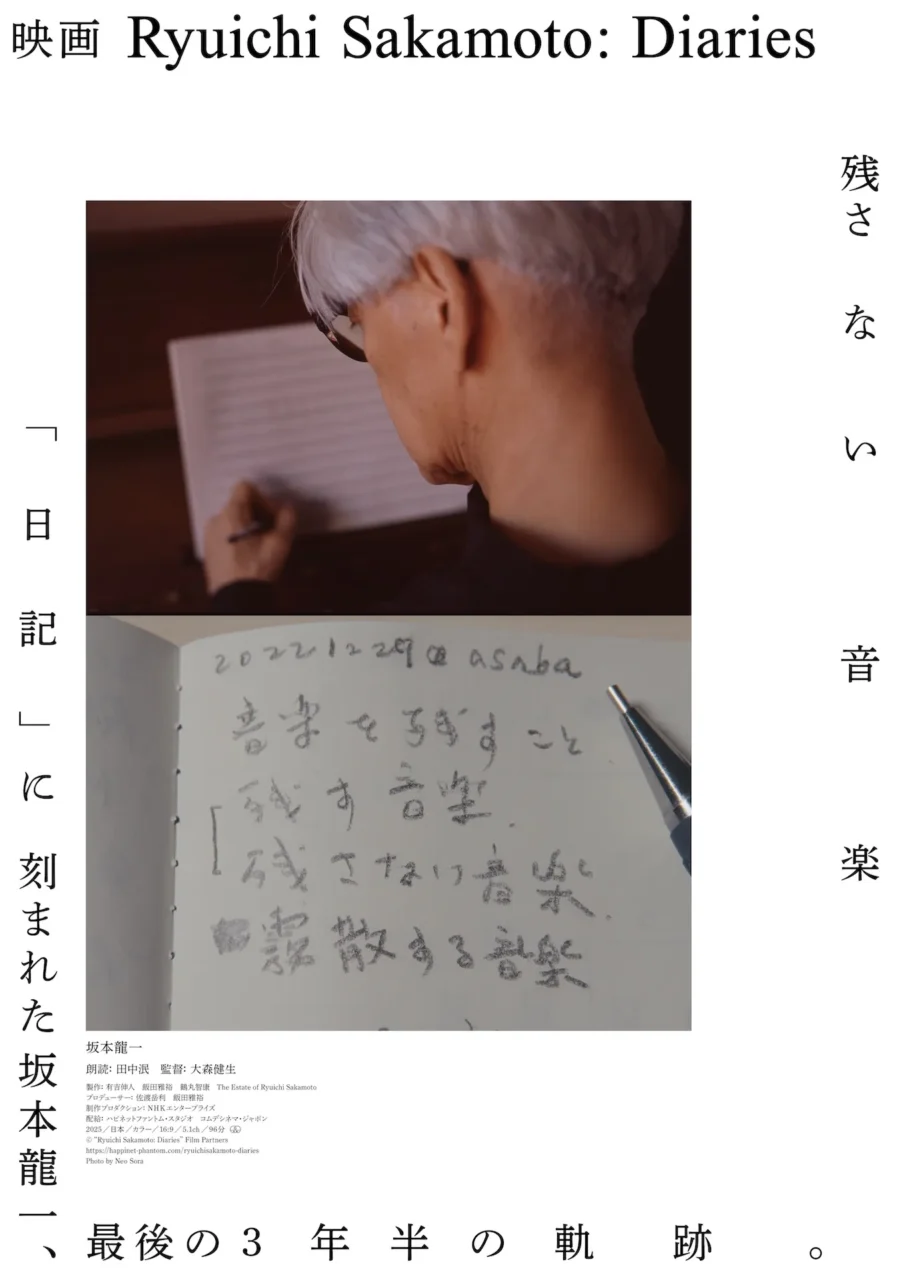

Ryuichi Sakamoto: Diaries

Release: November 28, 2025, nationwide at TOHO Cinemas Chanter and other theaters

Ryuichi Sakamoto

Narration: Min Tanaka

Director: Kensho Omori

Producers: Nobuto Ariyoshi, Masahiro Iida, Tomoyasu Tsurumaru, The Estate of Ryuichi Sakamoto

Executive Producers: Taketoshi Sado, Masahiro Iida

Production Company: NHK Enterprises

Distribution: Happinet Phantom Studio, Comme des Cinéma Japon

© “Ryuichi Sakamoto: Diaries” Film Partners